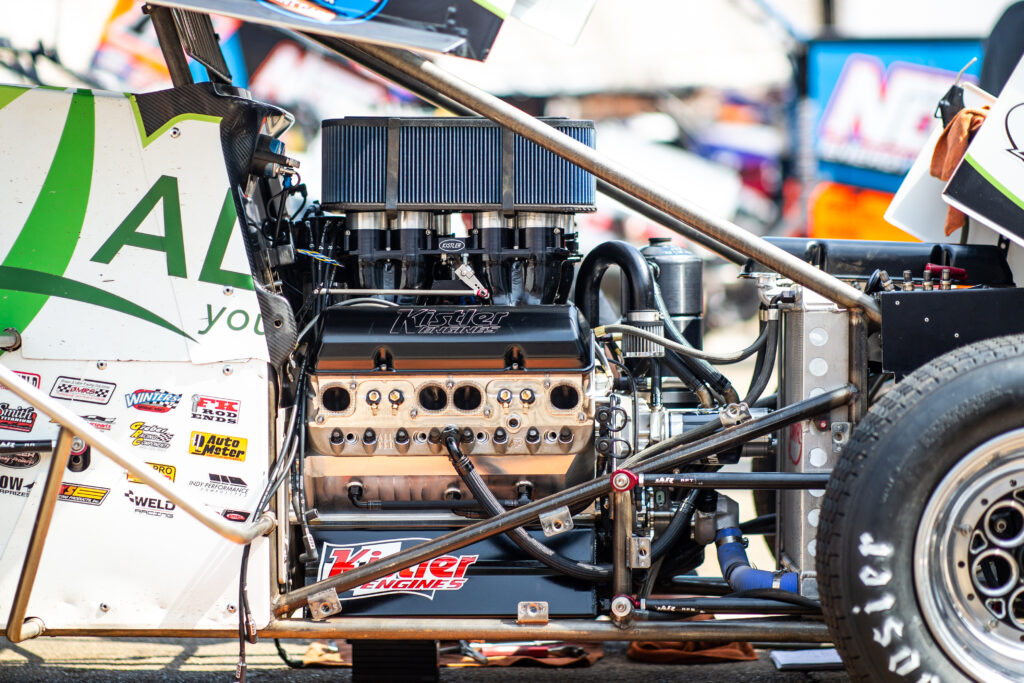

April 10th is National Sprint Car Day. Why? The 410 cubic-inch engine is the power plant of choice for top-tier sprint car series. The engine is an aluminum block pushrod V-8, typically based on a small-block Chevy, though many teams run Ford, Dodge, or Toyota variants. The naturally aspirated, methanol-injected engines are capable of producing over 900 horsepower at over 7000 rpm. Bolted into a car weighing 1400 pounds dripping wet, the end result is a power-to-weight ratio that tops that of a modern Formula 1 car.

While 410 is likely a familiar number to any sprint car fanatic, the origin story behind the engine’s widespread adoption is a bit more obscure. Back in the day, dirt and paved bullrings dotting the continental countryside were disparate in their engine rules. The hot shoes in Pennsylvania may opt for a big-block V-8 while Midwesterners in Iowa may bore out a 350-cubic-inch small-block. Others opted for GM’s 400-cubic-inch small-block. The variations made it difficult for locals to run with touring sprint car series, like the World of Outlaws, when they came to town. It also required traveling Outlaw teams to pack heavy, with multiple engines, or be outrun.

Ahead of the 1985, World of Outlaw founder Ted Johnson implemented a maximum displacement rule to help unify sprint car engine builders and keep costs down. “It started out as a basic 400 steel block in the 1970s, and then when you oversized it, you started getting 406, 408.,” says renowned engine builder Joe Gaerte. “Then, they basically rounded it up so you could have a couple rebuilds.”

“The rule was good and everybody was good with it because it was getting out of hand,” says Gaerte. “People had 440s and 450s and they were doing crazy stuff. They were still using a 400 block and trying to put a big stroke in it. It was just a mess.”

Now, aluminum ancestors carry the 410 torch and the unifying rule that Johnson debuted nearly 40 years ago still stands.

The lightweight predecessors are relatively bulletproof, but that doesn’t prevent teams from testing tolerances. Occasionally they’ll grenade. No matter. The rather spartan sprints paired with a roster of crew members (often sourced from rivals teams willing to lend a hand) allows for teams to change engines in the middle of the event. Some well-planned choreography can have a new block between the frame rails in less than 15 minutes.

The swap may come quick, but it doesn’t come cheap. A brand new Speedway Motors Chevrolet 410 engine will set you back about $60,000. The small-block beast produces 950 horsepower at 7,200 rpm and 730 lb-ft of twist at 5700 rpm. On the other side of the aisle, Ford Performance recently developed a new 410 engine for sprint competition. Based on the Ford Windsor V-8, the engine puts out similar 900-plus horsepower figures, but lacks the general adoption of the Bowtie block.

Check out the gallery below and raise one up for the mighty 410!

The 410 cubic-inch, alcohol-chugging motor connects to a coupler known as the “in-out box,” which connects to the driveshaft. Sans trans! The driver sits on top of the live rear axle, upright like they’re sitting at the dinner table, legs straddling the driveshaft, elbows up reefing on an oversized steering wheel. Chicken wire prevents dirt clots from doming drivers.

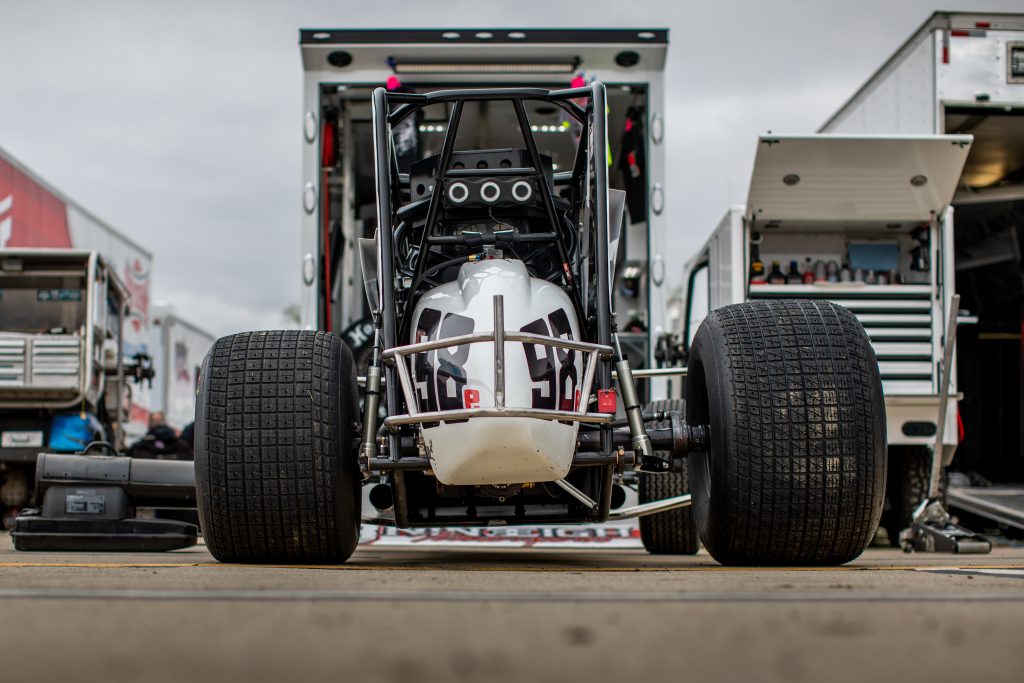

Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, sprint car teams experimented with wings and other aero implements for added downforce. This eventually split the family tree into two distinct branches—winged and traditional (non-winged) sprint cars. Rulebooks mandate the size of the wings—typically 24 square feet in size.

Short tracks, ranging from quarter- to half-mile ovals, and a clay surface helps to keep sprint car speed below supersonic levels. Even on a half-mile track like Bristol (dirt), speeds can average well over 100 miles per hour.

A view from the back of a sprint car highlights the offset rear axle and stagger (difference in diameter between left and right tires). Both are a necessity for cornering quickly. The round tail is actually the car’s fuel cell, emblazoned with the driver’s number and protected by chrome tubing.

A short wheel-base, a short rear gear, and giant grooved Hoosiers are the proper ingredients for killer wheelies.

Many NASCAR drivers got their start on dirt and a few, including fan fav Kyle Larson, return to their roots to run sprint cars.

Knoxville, Iowa is widely considered the epicenter for sprints as it is home to the Knoxville Nationals (the Daytona 500 of sprint car racing) and the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame.

Unlike Knoxville, Gas City Speedway doesn’t have barriers on the backstretch.

No catch fence, no problem.Ford GT40, Porsche 917; add “sprint car” to the Gulf livery roster.

The cage stand—or a wing stand—is a staple for any victory lane celebration. Upon winning the driver usually parks the car on the front stretch of the track and climbs on top of the car while saluting the crowd.

Until next year!