The tape rolls. Two Detroit junkers sit side-by-side in a Missouri field. A few yards away, a blue Ford F-250 idles loudly, chrome glinting in the sun. After a beat, the truck flings forward, tires churning mud. The Ford slams into the two cars head-on, roaring over them, leaving craters in the trunks. Then it charges offscreen.

A cut in the tape. The Ford is back in position. Another stab of the throttle, and the truck lunges back toward the scrap. This time, though, the driver punches the brakes halfway through. The beast heaves to a halt atop the cars. Glass shatters. Behind the camera, a kid bursts into laughter.

There it is.

The Ford’s driver, in shades and a cowboy hat, opens the door to take in the view. Then he backs up the truck, crushing the cars further into the clay. The kid can’t stop laughing. The Ford dismounts the heap. Its air horn bellows.

In the spring of 1981, that fuzzy VHS recording was a shot heard ’round the world. It documents the moment when Bob Chandler, in a primordial version of the world’s most famous monster truck, became the first man in history to crush a car with a 4×4.

Or did he?

Texan Jeff Dane also says he was the first. That his truck, a jacked-up diesel F-250 named King Kong, was the first to publicly crush a car, at Wisconsin’s Great Lakes Dragaway. This is how early monster-truck stories go. Ask ten different fans where the sport came from, you’ll get ten different answers. A fleet of overbuilt 4x4s evolving into a billion-dollar industry—that trajectory sounds a lot like fiction anyway. Back in the day, the stories weren’t kept in books, just shared through local newspapers and word of mouth.

Either way, on that cold Missouri farm, Chandler discovered the importance of showmanship. His first take was procedural, the second drawn out and dramatic.

The guy at the wheel looks down, one hand out the window, crushed cars reflecting in cheap sunglasses. He is no longer just a carpenter with a cool truck. He is Bigfoot.

The Ford was a ’74, the ’80s were just beginning, and the timing was perfect. America was about to go big hair and Reaganomics. Bigfoot would become the first monster-truck household name, and it fit right into the decade. Monster trucks were size and color and noise, Guns N’ Roses, Hulk Hogan, and Trump Tower all bound up in a day-glo wrapper. They were everything cool about a famously loud era and a wicked distraction from real life.

Tim Defrisco/Getty Images

The industry never stopped growing. Monster trucks are now purpose-built machines of nearly 1500 hp. They are designed to perform intense acrobatics, climbing, smashing, and soaring over virtually anything in their path. The franchised events that showcase the largest of those trucks, called Monster Jams, are a family affair, safe as milk and run with the technical efficiency of Grand Central Station. YouTube holds monster-truck cartoons and sing-alongs aimed at kids.

Monster Jam World Champion Tom Meents attempts a front flip with Maximum Destruction at MetLife Stadium, in 2015. (Dave Kotinsky/Getty Images)

To understand how all this came to be, you have to go back to the ’60s. When the Big Three began placing emphasis on off-road freedom. Ford’s scrappy little Bronco paired the utility of a Jeep with the comfort of a small sedan. The Blue Oval’s domestic rivals eyed the Bronco’s booming sales and quickly turned out similar offerings.

By the early ’70s, American trails were infested with sport-utilities. Off-roading was booming, especially on the West Coast, where hot-rodders took to the dunes with tube-frame contraptions on balloon tires designed for Arctic exploration. In this world, in 1974, Missouri’s Bob and Marilyn Chandler purchased a brand-new Ford F-250. They enjoyed camping and off-roading with it but quickly became frustrated with the lack of 4×4 parts available in their home state. In 1975, they partnered with friend and fellow off-roader Jim Kramer to start Midwest Four-Wheel-Drive, an aftermarket supplier near St. Louis.

The F-250 served as Chandler’s shop truck, but it also was a catalog showcase. Before long, Chandler and his souped-up Ford were local celebrities, making short work of local off-road events. But also short work of the truck’s components. Chandler earned the nickname “Bigfoot” for his aggressive driving style.

Chandler was a carpenter by trade. Rather than replacing broken pieces with similar equipment, he opted to upgrade his truck with heavier-grade parts. “I never had the thought to build a monster truck,” he said, in a 2010 interview. “I kept putting bigger tires on it. Then I broke axles, so put bigger axles on … Then I didn’t have enough power, so I put a bigger engine in … It was a vicious circle for three and half years.”

After months of mission creep, Chandler’s truck was a behemoth. Riding on tires four feet tall and the 2.5-ton axles of a military top-loader, Bigfoot could perform crab walks and tilt its front clip. A 640-cubic-inch Merlin big-block sat between the front fenders.

(Superroop/Flickr)

Chandler thought his truck could drive over anything, including junkyard cars. In 1981, inspired by a tough-truck competition on ABC’s Wild World of Sports, he and Kramer put that idea to the test. The duo took the blue Ford out to a friend’s barren cornfield, where they made that tape with the laughing kid. The car-crush clip was spliced into a promotional video that played on a loop at the Midwest Four-Wheel-Drive office. A promoter noticed the footage during a visit, asking Chandler to recreate the stunt for a sideshow at a regional tractor pull.

Chandler was hesitant at first, worried about sullying his truck’s image. But he eventually agreed. Fans went wild.

“Another surprise is in store at the Pull-o-rama. By popular demand, Bigfoot! The mammoth 1974 Ford featuring dual steering axles and weighing in at 9200 pounds, returns for a terror pull of its own.” – Marion County Fair advertisement

Chandler’s rig was quickly becoming a headliner—national newspapers, magazine covers, as a prop in the 1981 B-movie Take This Job and Shove It. From local fairs to stadium floors, farm-fleet fans were coming for the tractors but staying for the big Ford. At the Pontiac Silverdome one night, announcer Bob George referred to Chandler’s pickup as a “monster truck.” The name stuck.

(Bettman Archives/Getty Images)

The evolution continued, driven by fan appetite. Debuting in 1982, Bigfoot II sported a set of 66-inch tall Goodyear Terra tires—now an industry standard, but originally made for floater-spreader farm implements. In 1983, Chandler was invited on an episode of TV’s That’s Incredible, to race another lifted truck across a course made of junkyard cars. Chandler called on a friendly rival, Everett Jasmer, for the second truck.

Jasmer, a Minnesota drag racer, had met Chandler at a mud bog years before, and the two had stayed in touch. Jasmer’s Chevy K10, dubbed USA-1, was a proper foil to Chandler’s Ford, and so the two squared-off on national television. The race was a nonevent—Jasmer’s truck broke after just a few crushed cars—but the exposure spooled interest in the growing sport.

Other relationships were far less friendly. Builders and drivers argued over who did what first, but there was also intense competition to be the largest, the fastest, the most-booked. No rift was more volatile than the one between Chandler and Fred Schafer, two Midwesterners more alike than they’re probably willing to admit.

Schafer lived in Granite City, Illinois, some 25 miles from Chandler’s shop. In the mid-1970s, while Chandler was busy off-roading, Schafer was terrorizing local dragways. “I wasn’t quite fast enough and didn’t have financing to become professional,” he says. “But locally, I was the man to beat.”

One day, Schafer paid a visit to Midwest Four-Wheel-Drive to check out Chandler’s rig. “I don’t want to knock his truck, but it looked pretty rough,” Schafer says. (Like every drag racer, he revels in heads-up comparisons.) After seeing Bigfoot, he thought, “I’m going to go home and build me a Chevy truck. I don’t like Fords. Never did.”

By 1979, with the help of his buddy Jack Willman, Schafer was done. A self-described horsepower nut, he had transformed a ’79 Silverado into an alcohol-chugging beast with a blown 454 under the hood and “Bearfoot” painted across the doors. The moniker wasn’t a reference to his rival—it was an homage to Schafer’s pet American black bears, Sugar and Spice.

Schafer soon received offers to exhibit his truck—and his bears—at tractor shows. Each appearance paid $500. “Back then, there was only a few trucks in the United States,” he says. “We would be booked for months and months and months.” Ahead of a 1982 truck show in Wisconsin, a local rag advertised King Kong, Bigfoot, and Bearfoot as the only three monster trucks in existence.

Again, the claim’s validity hung on who you asked. What everyone seems to agree on: Those three put on the biggest and best shows.

Like Chandler, Schafer built additional trucks to meet spectator demand. Little Bearfoot, a 1982 Chevy S-10, became the first monster truck to utilize planetary axles—a pair of Rockwell PS115s sourced from a military front-end loader. To demonstrate his innovation’s strength, Schafer threw a log chain around a pillar of an interstate overpass, then hooked it to the S10’s rear. All four tires lit up when he stabbed the throttle. Schafter sent a photo to Petersen Publishing, the company behind Hot Rod magazine. The company immediately flew a rep to Illinois to recreate the shot.

Chandler eventually invited Schafer out to a Bigfoot appearance, a tractor meet in Ridgefield, Ohio. As the bear wrangler tells it, Chandler drove out first in his truck, grabbing the mic and introducing his competitor. (“When I came out in that Chevrolet, there were a whole lot more cheers.”) Elvis had been upstaged. “That was the first and last appearance with Bigfoot for about five years.”

Things only grew worse between the two men. In 1984, bearded rockers ZZ Top asked both drivers to lend their trucks for a music video. Schafer says Chandler named his price first. Not wanting to lose, Schafer quoted the band’s managers a much lower fee, earning the booking. Adding insult to injury, Schafer’s truck appeared in an episode of Knight Rider, in a TV pilot, in a Volvo commercial, in an ad for Coors beer. Bigfoot may have been the first monster truck in America’s living rooms, but Bearfoot felt like the only one on TV.

Somewhere in the middle of Bearfoot’s rise, Chandler sued Schafer over the trucks’ name similarity. Motive was unclear. The civil action turned relationship fissures into canyons. “It’s been ugly ever since then,” Schafer says. “Ugly.”

These were the salad days of the sport. As the ’80s progressed, more monster trucks were brought to life, names like Blue Thunder, Frankenstein, Monster Vette, Excalibur, Krimson Krusher, King Krunch. Most rigs in North America were what the business calls Stage II—planetary axles, a full rollcage, around a foot in suspension travel. Gone were the production frames that had supported early trucks, replaced by purpose-built or ex-military rails.

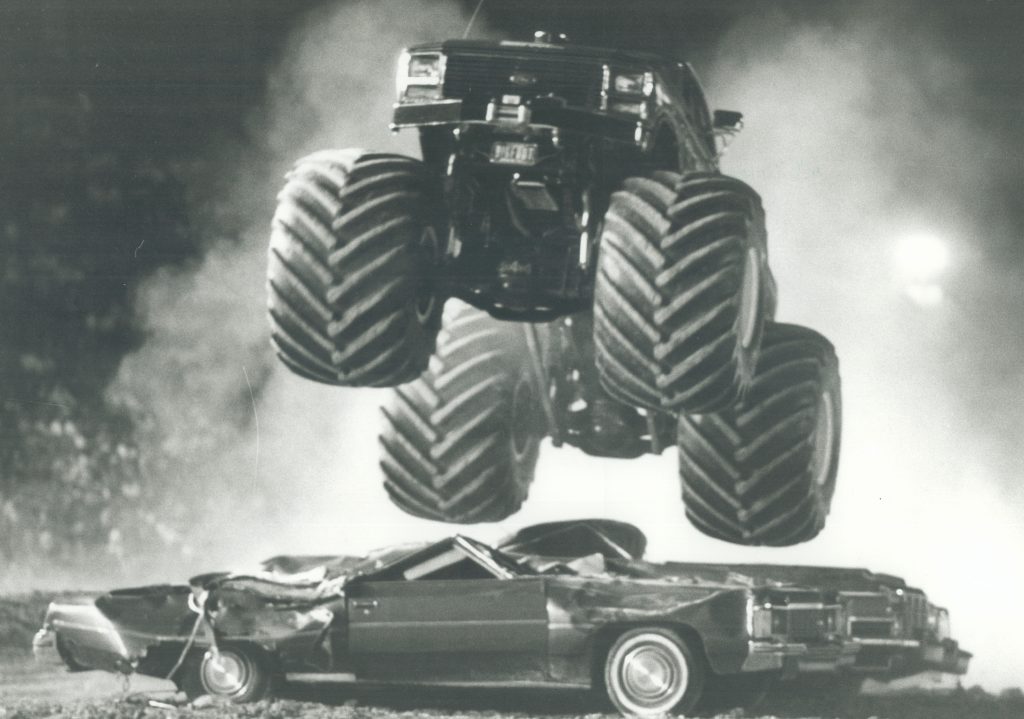

(Al Dunlop/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

Promoters heeded the packed stands and abandoned, limited-capacity fairgrounds. Football stadiums and 80,000-seat arenas were easily filled. Fans swung from the rafters chanting “Bigfoot, Bigfoot!” And yet the machines were still mostly unpolished, the drivers generally inexperienced. Trucks broke often, snapping axles or blowing engines, marooned on a pile of junk cars.

Keeping a truck running back then was a herculean task. Monster rigs had to withstand major punishment as their drivers ran full-steam into full-size Cadillacs and Lincolns, then landed on bare concrete floors. Owners quickly learned consistency was key.

(Luke Frazza/AFP/Getty Images)

“Some people thought this was going to be a fad, a flash in the pan,” says Jeff “Wildman” Cook, the founder of Auburn, Indiana’s International Monster Truck Hall of Fame. “You needed a reliable truck because that’s what promoters wanted. If all the trucks are broke, you’ve got unhappy fans.”

As many of those builders were drag racers, match racing was the logical next step. Moving on from running just a few four-wheeled stars at each event, promoters began to book more than a dozen a time. In 1988, truck- and tractor-pull sanctioning body TNT Motorsports staged the first-ever monster-truck race championship, the Monster Truck Challenge. Events were broadcast on ESPN, then a fledgling sports network looking to fill air time. The audience grew further.

With match racing, drivers now had a tangible goal: a finish line and a trophy. The 4×4 arms race kicked into overdrive. This third stage of evolution produced machines that were lighter, faster, and stronger than ever. Aluminum and fiberglass replaced steel, and the chassis and roll cage grew into one integrated piece, like a period NASCAR stocker. Bigfoot 8 is generally agreed to be the first Stage III truck. Under a fiberglass body shaped like a 1990 Ford F-150, that tube-frame machine was a tech masterpiece, built from the ground up, its parts drafted on a computer.

(Boris Spremo/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

The exposure did not go unnoticed: Sponsor money was everywhere. Chandler had corporate funding from Ford and Mattel. Jasmer had Chevrolet and plastic-model company AMT. In 1992, Schafer signed a high-dollar deal with Dodge. The cash influx helped keep the spectacle on the road, and it helped teams build more versions of existing trucks, for more shows at once. Bigfoot alone had an entire fleet of Ford-sponsored offspring. Many were carbon copies of the original truck, while others were unique projects, like Bigfoot Shuttle, a lifted Aerostar minivan with 48-inch rubber.

- Bigfoot Fastrax at Anaheim Stadium in 1989. (Getty Images)

- Bearfoot became a Dodge Ram in the 1990s. (Picasa 2.7/Flick)

Naturally, fans demanded more. Ten years in, crushed cars and quick runs were no longer enough; people wanted airborne trucks, a feat then attempted by only the most daring drivers. The most reckless joined Bigfoot and Bearfoot as fan favorites. North Carolina mud-bogger Dennis Anderson built his first truck at 22 years old using parts plucked from local salvage yards. If Chandler was a builder and Schafer was a racer, then Anderson was a scrapper with dirty knees and a wink. His first truck, a 1952 Ford panel, was a hodgepodge of parts. Competitors teased him for the way it looked, to which he retorted, “I’ll take this old junk and dig your grave.”

Over time, Anderson upgraded his rig into a legitimate monster truck, able to withstand his aggressive driving. He beat Bigfoot and other stars on occasion, but he was most known for his conservative use of the brake pedal. And for the airbrushed skulls adorning his truck, Grave Digger.

(Beadmobile/Flickr)

“He used to be called ‘One-Run Anderson,’” Fred Schafer says. “He might only last one round, but that round was a dandy.” When Stage III trucks arrived, Anderson’s was a showstopper. His green and purple 1950 Chevrolet panel truck began to supplant Bigfoot as top monster draw. George Thorogood’s “Bad to the Bone” played on the PA at every show, announcing Digger’s arrival.

By 1991, money was being made hand over fist. The United States Hot Rod Association, the big dog in truck and tractor pulls, had recently purchased TNT, its competing sanction. The USHRA held exclusive booking rights to the top trucks, including Grave Digger. As the organization grew, its management noted the profit funneling to individual drivers and made a grab. “They used to give us $3000 for the show,” Schafer says. “We’d make about $12,000 in T-shirts—of which they would take about 40 percent—and we’d walk out with about ten grand.”

Bearfoot’s driver says the firm got greedy: “We’re going to give you a dollar per shirt. Take it or leave it.”

If that monopoly didn’t jibe with many drivers? Tough luck. The USHRA had an exclusive contract with every American football stadium on the calendar. The monster truckers had two choices: tolerate the new deal or leave. Bigfoot left. Grave Digger stayed.

- (LatinContent/Getty)

- (AFP/Getty)

Just like that, Chandler was out. The man from that Missouri cornfield, forced from the house he built. An industry built on showmanship kicking its number-one showman off the stage. Chandler’s performances were relegated to smaller stadiums and tractor pulls in two-horse towns. The USHRA became something like Formula 1 for top-tier truckers. Growth was still immense, but Bigfoot’s departure was a marker. The early days were now firmly in the past. Monster-truck shows still fill stadiums, but something is missing. The ’foot is history.

And so that is the story of how monster trucks came to be. Or at least, that’s what the man with the megaphone told me, and what I choose to believe: Salute Jeff Dane, don’t mess with Sugar or Spice, Bigfoot got screwed, and Bob Chandler is still the king. No matter what anyone says.

Don’t believe it? Find your own field and ask someone else.

(Tony Bock/Toronto Star/Getty Images)