One of Formula 1’s classic races, the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, is also the fastest race of the season. In honor of the Italian GP scheduled for September 11, we look back to 1971 when it resulted in the closest finish in F1 history and a very unexpected winner.

In racing, it doesn’t matter where you qualify: It’s where you are at the checkered flag that counts. That was one of things that went through Peter Gethin’s mind as he lined up 11th in the Italian GP’s 24-car field.

Gethin, a chirpy horse-racing jockey’s son from just south of London, started sensibly rather than spectacularly. The 31-year old left the heroics to other drivers and the race lead changed four times in the first 10 laps. Nonetheless, he’d stayed in touch with the lead pack from the start.

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Monza was, and still is, the ultimate slipstreaming circuit on the F1 calendar. Before the chicanes were introduced in 1972, pretty much the whole lap was a flat-out dash. Even more than now, drivers used the hole punched in the air by the car in front to draw them along. Then when the time was right, they’d pop out of the slipstream and cruise past their rival.

As every driver at Monza knew, the start-finish straight in the run to the checkered flag would be the key to winning this race. But Gethin believed he had one big advantage: the gutsy V-12 in the back of his BRM.

At the mid-point of the race, the Briton was tussling with the McLaren of countryman Jackie Oliver. There was history here. Peter had been a McLaren driver until two races previously. He’d made his F1 debut for the British team in 1970 when it was struggling to pick itself up from the sudden death in a high-speed crash of team boss Bruce McLaren.

Then weeks before the Italian Grand Prix, McLaren chief Teddy Mayer had told Gethin that Italy would be his last race for the team. Fortunately for Peter, BRM had offered him a way to stay in F1 and he left McLaren before the previous race in Austria. It was Oliver who’d taken his seat.

Using 500 of the V-12’s revs more than he’d been told to before the race, Gethin dealt with Oliver and started cruising up to the leading bunch. This had comprised Ferrari’s Clay Regazzoni and newly crowned champion Jackie Stewart. But by lap 17, both were out with engine trouble, as was the other Ferrari of front-row starter Jacky Ickx.

The man doing most of the leading was Ronnie Peterson in the March. But perhaps the favorite was Chris Amon in the screaming V-12 Matra. He’d qualified on pole position and the former Ferrari driver was desperate to win his first Grand Prix. He’d already led nine laps and was well in the mix.

Grabbing for the oil-streaked tear-off visor on his helmet to get a better view of the race’s final laps, the famously unlucky Amon inadvertently took hold of the whole visor. Ripping this off, his eyes now had no protection from the 200 mph wind rushing by. Vision impaired, he dropped back.

The race now looked to be between Peterson, Stewart’s Tyrrell understudy Francois Cevert, Mike Hailwood in the Surtees and Howden Ganley in Gethin’s sister BRM. Peter was just behind in fifth but had no intention of staying there. He knew the win was up for grabs.

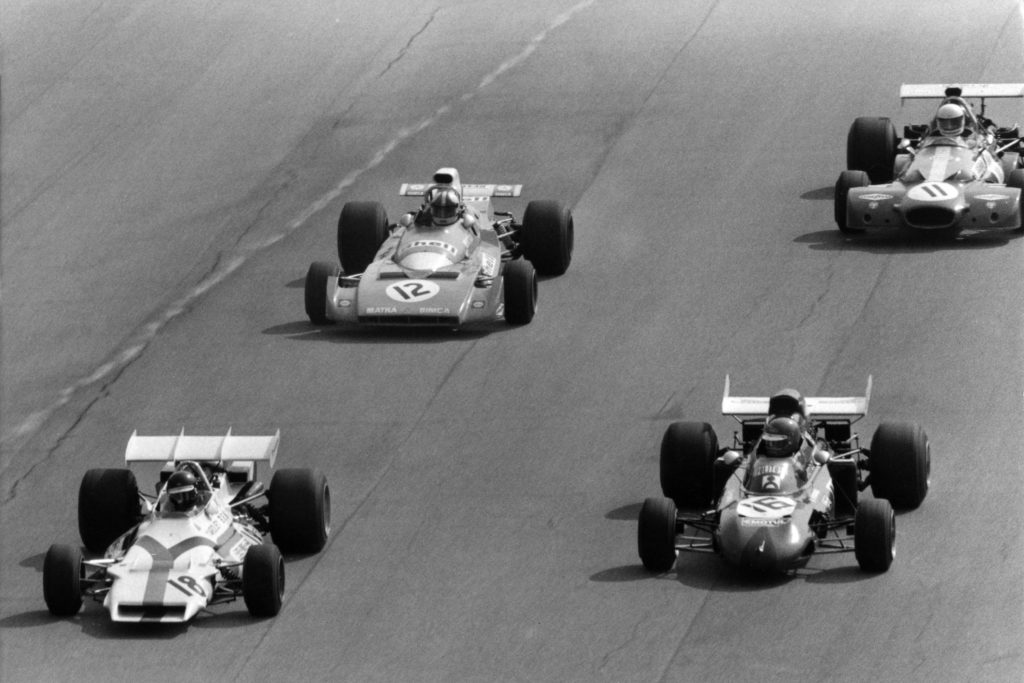

Ronnie Peterson battling for the lead with François Cevert. Photo: Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Slowly and pretty much unnoticed by the four leaders, the BRM edged closer and on laps 52 and 53 out of 55, he led. Peterson certainly hadn’t realized the Briton was a serious contender. “I was trying to work out how to beat Cevert – he was the one I really had to watch,” he later told his team boss Max Mosley. “I knew I must lead into Parabolica because he hadn’t the speed to pass me between there and the finish line.” Parabolica is still a feature of Monza. A long, high-speed right hander, it leads drivers onto the start-finish straight at the end of the lap.

As the cars started their final lap, Peterson’s red March was leading Cevert’s Tyrrell. Braking for Parabolica, that last time, it was the Tyrrell that had the advantage. But Ronnie had positioned his car perfectly to nick the lead from the blue car and sprint to the checkered flag.

Outbraking the Tyrrell, as he’d intended, Peterson then ran slightly wide. No worries, he should still have the momentum to win the dash to the flag. Except when he checked his mirrors, a white car was filling them. Scrabbling for grip and in a cloud of dust on the inside, Gethin passed both the March and Tyrrell and planted the throttle to start the drag to the finish flag, flexing the muscles of the mighty BRM V-12.

Racing and slipstreaming on the Monza straight saw Peter Gethin (18) win in dramatic fashion. Photo: Getty Images

Peterson swung the red car to the right, as close behind the BRM as he dared, to pick up its slipstream. He felt the tow from his rival and as they got to within 100 meters of the flag, he jinked out to the left. His car began to surge closer to the lead thanks to the effect of the slipstream.

Cevert on the outside of Peterson was trying to outrace them both, and Hailwood’s Surtees was still only a yard or so behind. As the flag neared, Gethin shot his right arm triumphantly in the air, knowing that perceptions could play a significant part if the finish was as close as he thought.

It was. But the power from his V-12 had got the better of his four Ford Cosworth-powered rivals. He’d won the race by inches, 100th of a second ahead of Peterson, who was 800th of a second in front of Cevert. Hailwood in fourth was still less than a tenth of a second behind Gethin.

Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

It remains the closest finish F1 has ever seen. And with an average speed of 150.75 mph it was the fastest grand prix ever run for years.

As for Gethin, he’s credited with leading a grand prix for a mere three laps and 10.7 miles, all of them at that Italian race. And over a Formula 1 career spanning five seasons he scored just 11 points – nine of them for his win in Italy. Being at the front when it counted really was all that mattered.

***