Fifty years ago, the Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) was facing an identity crisis. While SCCA’s pro series were thriving, amateur categories were racing toward the old folks’ home. Realizing that something had to be done to inject fresh blood into its membership ranks, this crusty club of wealthy Jaguar and Ferrari owners took decisive action ahead of their 1972 season.

The SCCA’s invention was a new category called Showroom Stock Sedans (SSS). Its class consisted of small, inexpensive cars that could be raced competitively with minimal preparation. Bolt in a roll bar, add a fire extinguisher and belts, paste numbers on the sides, and the car was track ready. Budding Marios only had to complete two driver’s schools before donning Nomex and a crash helmet to race.

The Showroom Stock part of the label was no exaggeration. Running stone-stock engines, street tires, and mufflers, the eligible econoboxes could be driven to work and raced on weekends, providing no fenders were crunched in the heat of battle.

The initial roster consisted of eight imports and their domestic rivals–the Chevy Vega and Ford Pinto. None of these boy racers cost over $2600 brand new, so a prospective driver could be armed and ready to compete for less than three grand, total. To curtail cheating, SCCA officials conducted tech inspections before every race. Also, a claiming rule allowed a fellow competitor to seize a demonstrably fast car post-race for $500 over its window sticker.

Buff book plunge

Showroom Stock was a dream opportunity for Car and Driver, the enthusiast magazine that prided itself for taking readers along for the ride whenever possible. After witnessing the inaugural race at California’s Riverside circuit, executive editor Patrick Bedard mustered nine cars (all that could be had at the time) for instrumented testing at Ontario Motor Speedway.

My job, as the magazine’s recently recruited technical editor, was to accurately document each car’s performance, using a fifth rolling wheel attached to the rear bumper and a strip-chart recorder lashed to the passenger seat. We also swapped in nine different radial tires to find the best stock rubber.

Upon testing, we found the Volkswagen Super Beetle, the Renault 12, the Toyota Corolla, and the Fiat 124S hopelessly slow. The Opel 1900 and Chevy Vega scored the highest cornering limit—0.75g. We eventually narrowed our list to the five best: the Vega, Datsun 510, Dodge Colt, and Ford Pinto.

Semi-pro, semi-fast

Between the west coast test sessions, Bedard and I enrolled in a week of training at the Bob Bondurant school of high-performance driving. Then, back on the east coast, I signed up for another driving school, held at Thompson, Connecticut, in the spring of 1972. To my everlasting chagrin, my fellow classmate was Paul Newman launching his illustrious competition career with Bob Sharp Racing.

Proving that auto journos are genuinely blessed humans, I found myself ready, willing, and certainly able to begin competing in local Showroom Stock races. Instead of investing in a car, I took command of Car and Driver’s Ford Pinto–which was already broken in by a 25,000-mile endurance test. After bolting in a roll bar and safety harness, upgrading the rubber to shaved Semperit radials, and affixing “00” stickers on the doors, I was ready to rumble. Nearby Lime Rock, Bridgehampton, and Pocono circuits would be my battlegrounds.

I literally got a leg up on Bedard because of an injury he suffered crossing Newport Beach’s Balboa Boulevard. (A witless motorist hypnotized by spring break babes plowed into pedestrian Bedard.) I raced away the summer of ’72. He was stuck in a hip-to-toe plaster cast.

After winning my share of Showroom Stock events and honing my skills at Lime Rock during open-track Tuesdays, magazine management agreed the time was right to share this experience with our faithful readership.

Conceived by Bedard, the Showroom Stock Sedan Challenge the most interesting motorsports advancement since the first Indy 500. For a one-dollar entry fee, competitors could race at Lime Rock on the second Saturday in October and compete for a $5000 purse. That was big money back then. Spectators were admitted for five bucks and offered free(!) Schaefer beer in unlimited quantities. Car and Driver’s sales staff wined and dine clients, while spectators knocked back bottomless beers.

Connecticut’s fall foliage was at peak color. 77 racers pulled in the paddock, and 7500 spectators lined the track. Starting positions for the two ten-lap heat races were drawn from a hat. The resulting finishes set the grid for the 25-lap main event. Car and Driver was well-represented–Pat Bedard in an Opel 1900, associate editor Jim Williams driving a Dodge Colt, and yours truly in the magazine’s Pinto that we affectionately dubbed The Reader Beater.

The race was only slightly less frantic than the Blitzkrieg. Bumping and banging were standard operating procedures. Passing on the grass on the front straight provoked huzzahs from the spectators but nary a raised eyebrow from the few flag wavers on hand. Spinouts and two-wheel teetering through the bends were commonplace.

“On the first lap I was inches behind a clump of cars rubbing flanks, trading paint, and jinking for any opening when a piece of chrome came off a car and flew up and over all of us,” says Bedard. “Nobody lifted. Egos were at full throttle, hellbent on a mad chase for a few bucks of prize money and a few moments of glory. I was as crazy as all the rest. And loving it.”

Unfortunately, little glory was earned by the buff book staffers behind the wheel. Bedard was shunted off the track early and witnessed most of the event sitting on his Opel’s decklid (not far from what was later revealed to be Southern Connecticut’s largest rattlesnake nest).

Veteran Bruce Cargill and I raced for lap after lap well ahead of the pack. He had significantly more speed through the track’s only left turn, I was quicker everywhere else. We traded the lead several times without incident.

Then Cargill wielded his kill shot. With me hard on his tail, he spiked his brakes one extra time mid-Big Bend for no good reason. Utterly shocked, I smacked his rear hard enough to collapse my poor Pinto’s hood and hole my radiator, which dispatched me to the pits. My consolation prize was $600 for leading race six laps.

Williams was the only scribe to take the checkers. Unfortunately, his sixth-overall finish didn’t earn a penny of prize money. Sorrows were subsequently drowned in an excess of Schaefer suds.

Nonetheless, the Car and Driver Challenge was deemed such a success that it was repeated each October for four more years. Bedard racked up successive victories in 1973 and 1974 to get his serious racing career off to a convincing start.

The last event, circa 1975, was arguably the most entertaining. Saab’s USA importer flew Swedish rally ace Stig Blomqvist over to race a Saab 99GL at Lime Rock. He and Bedard, in similar Saabs, traded the lead for several laps. Blomqvist held off his challenger with a creative left-foot braking technique. With the throttle flat on the floor, adroit taps of the brake pedal pivoted Blomqvist’s car in tight bends. Each of these maneuvers caused Bedard to lose a few feet of position, resulting in a half-second loss to the shrewd Swede.

Lasting Effects

Showroom Stock served as the ideal launch pad for Car and Driver to take its readers along for the ride in the wealth of motorsports that followed. Shortly after the first Challenge race, a well-equipped Long Island City, New York, garage was christened and staffed for the construction of race cars, project cars, and the development of leading-edge testing procedures.

Bedard rocketed up the racing ladder with a 1979 24 Hours of Daytona drive in a Ferrari 512BB, Mini Indy open-wheel competition in 1980, and an IMSA GTO class victory at the 1982 24 Hours of LeMans. He also co-drove Bob Tullius’s Group 44 Jaguar XJR endurance racer in 1983 and ’84.

In his boldest move yet, Bedard entered the Indy 500 a whopping four times throughout the early Eighties. A mechanical failure in the 1984 race triggered a spectacular spin followed by a horrendous crash into the infield barrier. When Bedard’s March Indy car flipped and split into two major chunks, his safety gear worked as intended to protect him from catastrophic injury. One side effect of the mild concussion he received was memory loss. No longer able to remember why, exactly, racing was all he cared about, Bedard never again participated in any form of track activity.

A new editor-in-chief closed our beloved Car and Driver garage, sharply curtailing motorsports activities. But even after the magazine office moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1978, staff members continued to race. My final burst of speed was a 2012 run from zero to 201.7 mph in a $2-million Bugatti Veyron Grand Sport at the Mojave Mile. Appropriately, that feat was achieved in the Showroom Stock Exotic class.

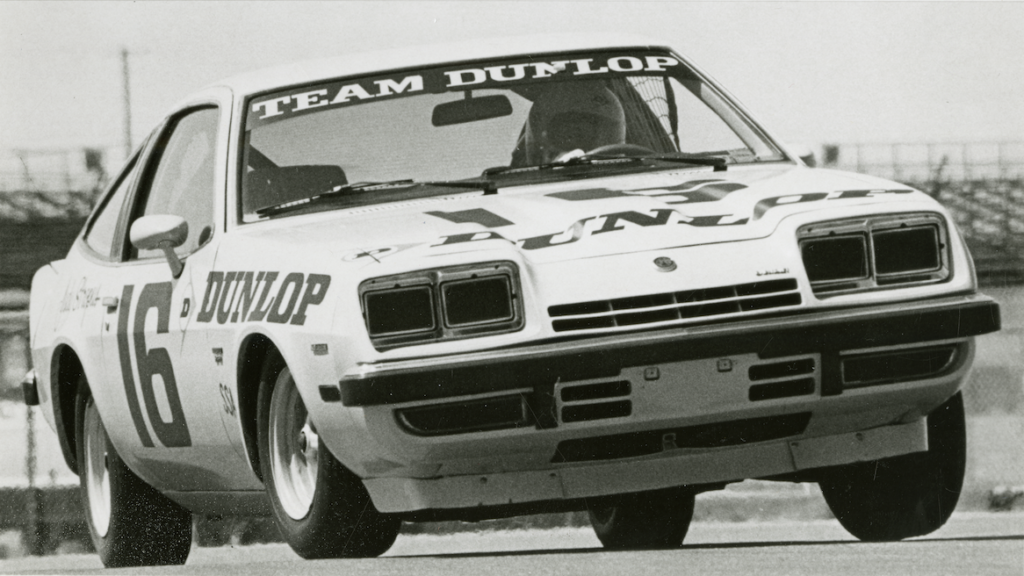

The SCCA’s archetype series evolved over the years. Reflecting on its own name prompted this organization to add a Showroom Stock Sports Car category, containing nine models in 1973. A GT class for Mustangs and Camaros followed in 1983. To level the racing field and in response to SCCA member requests, nominal performance modifications were allowed beginning in the late 1980s.

In 1996, the Showroom Stock category was renamed Touring and broken into numeric classes. Touring 1 through Touring 4 were assigned to cars based on performance capabilities. So, while class parameters changed to fit competitive pressures and car evolution, the SCCA’s Showroom Stock concept still thrives, fifty years after its inception.

- Lynn St. James

- Lynn St. James; #43 SSA

- Lime Rock; #7 Colleen Powers’ Fiat X 19

In 1971 I purchased my first brand new car, an Opel 1900 Rallye. It was an absolute joy to drive. For some strange reason it came from the factory shod with 2 ply, bias ply tires. I immediately replaced those with a set of Michelins accompanied by a set of Koni shocks. I wish I still had that great little car!

Interesting article from an ultimate insider! Sadly Showroom Stock racing in SCCA did NOT survive to this monumental anniversary. SCCA did not maintain the Stock in Showroom Stock, so the original class discussed in this article died 10 years ago, it was called SSC when it met its ultimate demise.

Fun while it lasted, the closest thing, SCCA has now is the resurrected BSpec, which is a very competitive class, and within shouting distance of the original concept.

For those on Facebook, Lime Rock public address announcer Greg Rickes has written an even -more detailed history of he Car & Driver challenge, it is available on the Lime Rock FB page. 😃

I ran a Show Room Stock Honda (SSC) for Friendly Honda in the Car and Driver Lime Rock race in 1975. During the prelim race I remember coming into big bend behind a group of SSB cars, some Saabs and an Opel. From what I recall as I approached the apex a front bumper flew over my head, another SSB went down the escape road and I was the first car out of big bend. My wife told me later that she had to hold Friendly’s owner from walking off the top of our motor home that was parked in the A paddock down by big bend because he was so excited. Any way, qualified for the final and finished 20th.

😆👍

Great article on the Show Room Stock class!

In 1997 or 1998 went to Skip Barber – One Day Driving School @ LRP – which got me involved in Auto X with my

1997 Plymouth Neon ACR. After a few years Auto X and some track days I got the idea of to go real racing with

the Neon. Had alot of fun racing – some good memories and still Auto X and on an occasional Hill Climb with my WRX,

with the Vermont Hill Climb Assocation. Keep on Motoring!