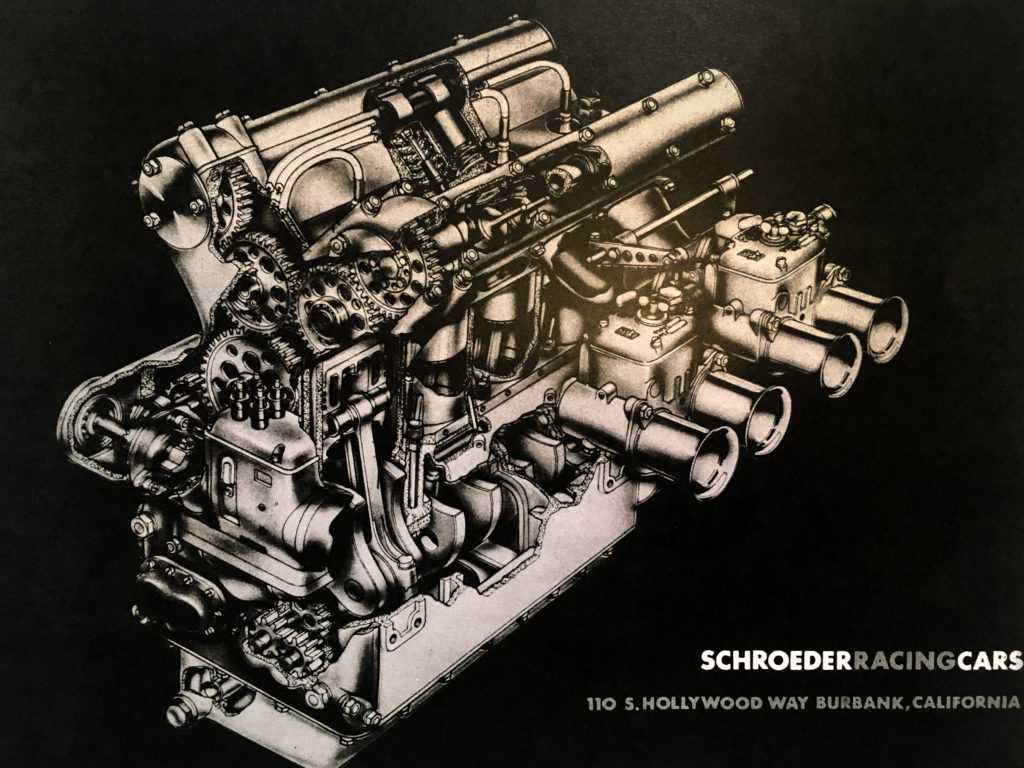

At first glance, the engine looks like one of the Offenhausers that dominated midget racing from the 1930s to the 1960s. I walk around the inline-four, observing its profile—a pair of slim, cylindrical cam covers balanced on top of a tall, narrow crankcase. Closer inspection reveals that it’s not an Offy at all. On the contrary, it’s a slick, remarkably clever motor that woulda, coulda, shoulda replaced the American four-cylinder if World War II hadn’t come along at just the wrong time.

“It was supposed to be the next-generation midget engine,” says Gary Schroeder, who owns the motor. “The Offy has two valves per cylinder and three main bearings. This has four valves per cylinder and five main bearings. It has a main-cap-style crankcase instead of a barrel crankcase. The cams are lubricated with pressurized oil instead of spreading the black stuff with a scavenge pump—which was a known shortcoming of the Offy. The engine even has insert bearings (instead of Babbitt bearings), which was really unusual back in 1939.”

Schroeder retired a few years ago, after decades of machining bulletproof steering boxes, torsion bars, springs and a host of other race car components at various shops in Burbank, California. He also enjoyed a long career as a midget driver here in the States and in New Zealand. And as the son of Gordon Schroeder, he’s a member of American circle-track royalty.

Gordon Schroeder was a young draftsman and would-be race car builder who made his first foray to the Indianapolis 500 in 1938 to help driving legend Ted Horn. Soon thereafter, he joined crack crew chief Riley Brett in an effort funded by wealthy sportsman Alden Sampson to escape from the long shadow cast by Harry A. Miller.

Miller was the foundational genius of American racing, and the magnificent cars he designed and built in the 1920s set standards that beggar belief even today, a century later.

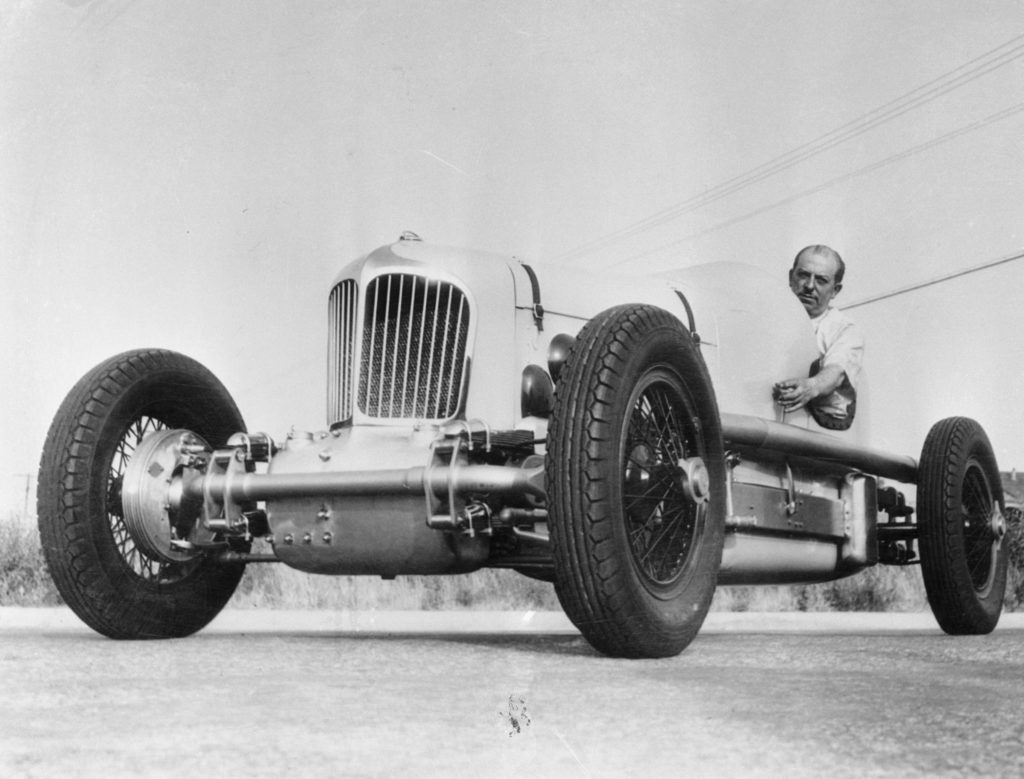

Harry A. Miller, seated in one of his many racing roadsters.

Miller was a maverick, but he wasn’t a one-man band. His empire was based on a triumvirate, whose other members were almost as influential as he was. While Miller was the protean big-picture man, mild-mannered engineer Leo Goossen put Miller’s ideas onto paper and virtuoso machinist Fred Offenhauser transformed the drawings into metal masterpieces.

After the stock market crash of 1929, racers could no longer afford Miller’s jewel-like straight-8 engines. Offenhauser struck out on his own to build automobile versions of the robust four-banger that Miller had developed for boat racing. This so-called Offy quickly emerged as the 800-pound gorilla of American motorsports.

As the Great Depression ground on, tiny, economical open-wheel single-seaters known as midgets emerged as the most popular form of racing across the country. Predictably, a smaller, less sophisticated version of the Offy Indy car motor became the dominant engine, rivaled only by hot-rodded versions of the Ford flathead, the V8-60.

In 1939, Sampson, Brett and Schroeder decided to build a better mousetrap, and Goossen was commissioned to design it. Although Goossen began with a clean sheet of paper, he naturally drew upon his vast experience with Miller and Offenhauser engines. The motor he fashioned was in many respects a new-and-improved version of the Offy, incorporating a pent-roof combustion chamber and exotic materials such as magnesium and aluminum—which added strength, reduced weight and improved breathing.

Although enough parts were amassed for a full production run, only two engines were completed and installed in race cars. They proved to be wicked fast when they debuted in 1940. According to legend, the high-pitched scream of the exhaust shook loose a quarter-century of bird droppings from the rafters of the grandstands at the Ohio State Fairgrounds—to the dismay of the fans sitting beneath them.

Racing was suspended after the attack on Pearl Harbor. After World War II ended, Schroeder bought the tooling, blueprints and rough castings for the Sampson motor. Midget racing never recaptured its pre-war glory, and plans to sell what was by then known as the Schroeder Engine were stillborn, despite its indisputable superiority to the venerable Offy.

Still, Schroeder dragged the parts around with him as he moved from shop to shop, and after he died in 1995, his son Gary kept up the family tradition. Today, Gary has a Burbank shop and storage facility where he maintains a fleet of stellar race cars—from cars built by his father to midgets he raced himself—along with an astonishing collection of vintage machinery, components, models, paraphernalia and filing cabinets filled with historic photos.

Last year, Schroeder decided to assemble a new version of his father’s old engine. As he puts it, “I got tired of moving the stuff around, and it was like, well, I’ve got blocks, I’ve got cranks, I’ve got cases, I’ve got a set of rods, I’ve got cam blanks. I’ve got some original pistons, but they’re cast, so I’d probably go to forged pistons. But pretty much everything is there.”

Schroeder is entrusting the build to Dan Brewer at Shaver Engines, a highly respected shop in Torrance with an enviable history in circle-track racing. Schroeder doesn’t have any long-term plans for the project beyond putting the motor together and running it on a dyno.

“I don’t care how much horsepower it makes.” He grins. “I just want it to make some noise.”

When it does fire, Schroeder should avoid the rafters.