Ahead of this weekend’s NASCAR race at Martinsville Speedway, we wanted to share our conversation with seven-time champion driver Jeff Gordon. Of his 93 career wins, 9 of them came at the half-mile paperclip in Virginia, the most for Gordon at any one circuit. Now retired, the veteran racer faces his biggest challenge yet: the C-suite at Hendrick Motorsports. –CN

Six days before we met Jeff Gordon in his office at Hendrick Motorsports, the four-time NASCAR champion rescued a lost and exhausted track volunteer at Phoenix Raceway.

The woman cried when he picked her up that dark night, after the fans and most personnel had gone home, unaware that the hat-wearing savior who drove her around multiple parking lots in search of her car is a top executive at a NASCAR superteam. When they finally found her car, the woman reported in a tweet, she asked if anyone had told him that he looks like Jeff Gordon.

“I am Jeff Gordon.”

- Gordon on the Hendrick Motorsports campus ahead of the 2023 NASCAR Cup Series season.

- Jeff Gordon awaits the start of the 1992 Autolite 200 NASCAR Busch Grand National race at Richmond International Raceway. (Photo by ISC Images and Archives via Getty Images)

Gordon started his career in open-wheel dirt racers.

In the woman’s mind, Jeff Gordon is probably a fresh-faced 20-something NASCAR star and spokesman for national brands like Pepsi, but that image, shared by millions, is from 30 years ago. Today, sitting in his meticulous office in North Carolina, Gordon is a little more seasoned, still trim and energetic, but graying at the temples. At 51, he is facing what he calls, “the biggest challenge of my career”—vice chairman of Hendrick Motorsports. He now oversees a racing organization of over 500 people, managing the sponsorships, PR, and countless other executive aspects. Critically, he will help guide the sport into the future. “Driving a race car came natural to me,” he says. “But this new deal is a steep hill to climb.”

Gordon’s office is on the second floor in the first building you encounter when you drive onto the Hendrick campus. You walk past a two-story, fully stocked trophy case and stroll along a balcony that overlooks the spotless shop floor. The 2022 season ended less than a week ago so the shop is unusually quiet, but over in one corner, a crew scurries around a special Camaro.

It’s the Garage 56 car—a modified version of NASCAR’s new-for-2022 stocker, the Next Gen car—that will race in the 24 Hours of Le Mans this June. The effort is a collaboration between NASCAR, Hendrick, and Chevy.

Gordon enters his office through a side door and invites me to sit down in one of the leather chairs surrounding a coffee table. He has set aside 90 minutes for this interview, and his commitment is refreshing. There is no assistant in tow, and Gordon puts his phone away. “I think one of my strengths is the ability to really stay in the moment.”

“Are you going to drive at Le Mans?” I ask.

“No.”

“OK, is that for sure?”

“No,” he says with a laugh.

Gordon has more or less lived at a racetrack his entire life. He raced as a kid in California, and his mother and stepfather nurtured his natural talent, moving to Indiana in 1986 so he could race fast, brutal sprint cars on Midwest tracks. By 1991, Gordon had found a seat in the Busch Grand National Series, one rung below NASCAR’s premier class. And then Rick Hendrick came calling.

Phoenix, 1991: Jeff Gordon racing in USAC Sprint competition at Phoenix International Raceway. (Photo by ISC Archives/CQ-Roll Call Group via Getty Images)

Hendrick, who had parlayed a used-car lot into a racing and dealership empire, quickly noticed Gordon’s speed and car control. Given Gordon’s rapid rise, he might have been an entitled upstart. Instead, Hendrick said he “found a mature young guy who was kind of humble. A little bashful. A sponsor’s dream.” Hendrick hired the young hot shoe to drive in the top class. Gordon’s first race with Hendrick was at Atlanta in 1992, the last race of the season—and also the final race for Richard Petty, who won 200 NASCAR cup races and is known by his nickname, The King.

“Hendrick is an amazing mentor,” Gordon says quietly.

“We hit it off so well that in 2000 I signed a lifetime contract with him and became an equity owner in the team.” Tragically, but importantly, a couple of years later, Hendrick’s son, Ricky, died in a plane crash. The implications were immediately obvious: Gordon, by then having already served more than a decade as a loyal and successful employee, then partner, to Hendrick, was the heir apparent. So even though Gordon had spent six years in the broadcast booth after he stopped racing, Hendrick Motorsports couldn’t have been far from his mind.

Gordon leans forward across the coffee table. “Rick knows that this place means the world to me, that I played a role in building it.” He gestures toward the shop. “And he knows that I want to be here building it for the future, too. So we haven’t really talked about anything beyond that.”

There’s clearly a deep bond and a shared passion between the two men. “He and I get to spend a lot of time together talking about life, talking about business,” Gordon says. “I think he knows how much I enjoy—maybe more than I ever thought I would—being in this role and figuring out the ways that I can help it continue to grow.”

Gordon’s spacious office is sparsely furnished, almost austere, but there are a few key mementos. A white helmet displayed on a shelf is signed “The King.” Atlanta 1992 was, in hindsight, a passing of the torch. Gordon’s arrival coincided with NASCAR’s evolution from its good-old-boy, southeastern roots to a national stage. In 1994, NASCAR became the first alternative series to race at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, with the inaugural Brickyard 400. Gordon won with a DuPont-sponsored car liveried with a colored rainbow. NASCAR abandoned North Wilkesboro Speedway, a storied track nestled in the moonshine foothills of North Carolina, to race in Texas and New Hampshire. In 1995, Gordon nabbed his first championship, beating another legend, North Carolina native Dale Earnhardt.

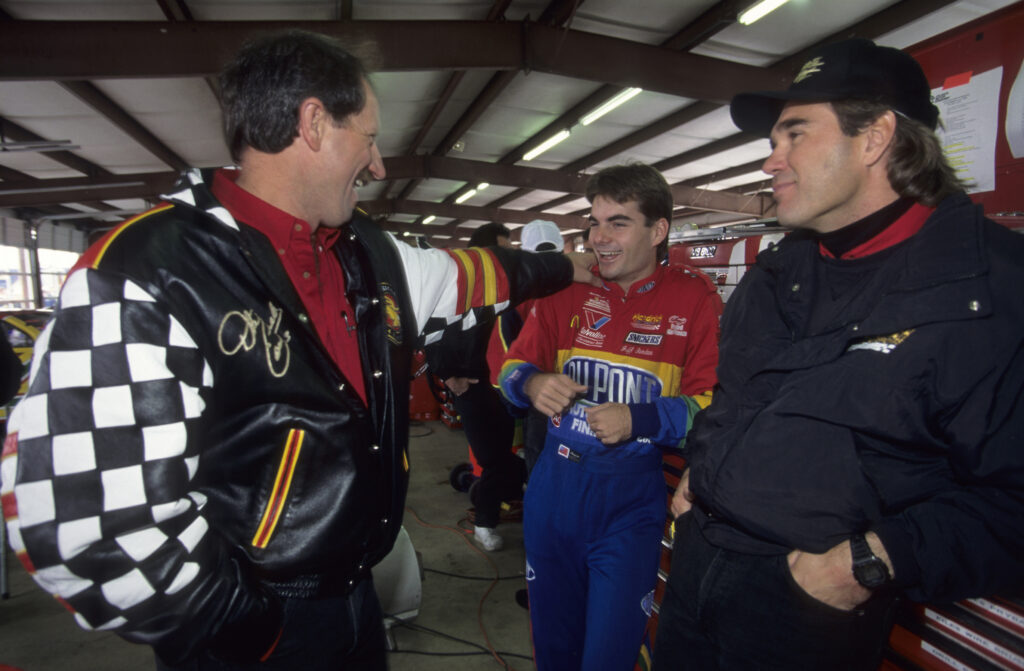

The magnitude of Gordon’s victory over Earnhardt cannot be overstated. Gordon was winning on the track but not in the court of public opinion, particularly among NASCAR traditionalists. The crowds were especially brutal, regularly booing the Californian. Although there’s a long tradition of shunning newcomers in favor of veteran drivers in NASCAR, the vitriol directed toward Gordon was remarkable. Fans, drivers, pit crews, seemingly everyone in the NASCAR circus was jealous of this young man for whom success came so easily.

With the benefit of distance, Gordon is philosophical.

“There were days that I was very frustrated with Earnhardt,” Gordon recalls. “I think because he and I had this rivalry, it made the sport better, it made me better. And I like to think it made him better.” Which is not to say that Gordon has forgotten just how nasty and dangerous the 200-mph rivalry became: “Other than the times he wrecked me at Phoenix and Michigan, I would say yes, I have nothing but good memories.”

- Dale Earnhardt (L) laughing with Jeff Gordon (C) and Gordon’s crew chief Ray Evernham before race at Atlanta Motor Speedway, in 1994. (Photo by George Tiedemann /Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

- Jeff Gordon and Dale Earnhardt before a 1996 NASCAR Cup race. (Photo by ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images)

Jeff Gordon (24), Mike Skinner (31) and Dale Earnhardt (3) in action during race at Daytona International Speedway.

(Photo by George Tiedemann /Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

Unquestionably, that rivalry, combined with his looks, youth, and success, vaulted Gordon—and, by extension, NASCAR—into the national spotlight. Even while the greater culture cultivated his emerging Hollywood image, traditional NASCAR fans were left cold, and in the garage, Gordon was considered a cream puff. It didn’t help when he married Brooke Sealey, a model working as Miss Winston, in 1994. At the time, drivers dating Winston models was an unwritten no-go, so the marriage invited more criticism. The couple divorced in 2003, an event Gordon now refers to as one of several humbling experiences:

“There’s always something to bring you back to Earth.” In 2006, Gordon married Belgian actress and model Ingrid Vandebosch, and they have two children.

Ray Evernham, Gordon’s crew chief throughout the ’90s, remembers all the brouhaha well. “I don’t think people appreciate just how tough Gordon is,” he recalls. “This slick young kid from California had a crew chief from New Jersey and a rainbow-colored car. Back then, NASCAR was all tough-guy veterans. Some days, it felt unsafe to just be at the track.”

In another break from NASCAR tradition, as part of a 2003 publicity stunt, Gordon drove a Williams Formula 1 car, while Indy 500 winner and Williams driver Juan Pablo Montoya drove Gordon’s #24 stock car. “That was a special moment for me,” he remembers, pointing at the steering wheel from the Williams car, sitting on another shelf. “There’s no other race car that gives you that kind of intense feedback and experience like a Formula 1 car.”

The Williams F1 steering wheel is a memento of Gordon’s car swap with Montoya.

Gordon got within a half-second of Montoya’s pace, leading pundits to suggest that he might move to the international series. “Could I have done it?” Gordon asks, rhetorically. “No. You cannot become a Formula 1 driver in your mid- to late 20s. The racing is so much different because, for one, the tracks are road courses. I grew up racing on oval tracks.”

I detect no regret in his answer. “I’d rather race in NASCAR. The competition is better and there’s less difference from car to car, so the pureness and skill of the driver plays a bigger role.”

That was certainly the case in the tumultuous, hard-fought races of 2022, Gordon’s first full year on the job. As we walk out of his office and toward his parking spot behind the building, Gordon reflects on the intense season. The Next Gen car offers very few opportunities for teams to fashion a technical advantage, so there were 19 different winners—including four who drive for Hendrick—which is a big win for fans. Although Hendrick’s star driver, Chase Elliott, was in the fight for the championship all the way to the last moments of the last race, ultimately the trophy went to a Penske driver, Joey Logano.

Chase Elliott and Gordon talk on the grid prior to the NASCAR Cup Series Championship at Phoenix Raceway on November 06, 2022 in Avondale, Arizona. (Photo by Jared C. Tilton/Getty Images)

“My role competition-wise is much different than people think,” says Gordon, as he gets behind the wheel of his black Chevy Suburban and motions me toward the front passenger’s seat. “People think, ‘Jeff’s won 93 races and four championships. He’s gonna be in there driving the conversations.’ And that’s not true at all. I’m really more in the background. We’ve hired smart people, we’ve put the best drivers, the best crew chiefs, the best engineers together. Now how do we continue to give them the tools to do what they do best?”

This leadership philosophy was honed during his days with Evernham. “Jeff has no problem being brutally honest,” says Evernham, “Deep down, however, he has huge empathy and compassion for people.”

“You’ve got to respect that racing,” says Gordon, “is not an individual sport. It’s a team sport. The driver is only as good as the car and the team.”

Many drivers echo similar sentiments, but by nature and perhaps out of necessity, drivers are selfish creatures. Gordon proved his exception to the rule when, in 2001, he encouraged Hendrick to invite the next young prodigy, Jimmie Johnson, to join their powerhouse team. It must have stung a little during the 2007 season, in which Johnson won the championship while Gordon finished second. Johnson went on to win seven NASCAR championships with Hendrick Motorsports, three more than Gordon, who later said, “I’ve never raced with anyone better, and that’s why I respect him so much.”

“Jeff is incredibly intelligent and sees out a very big windshield,” says Evernham.

Gordon won four races in 2014, but the stress—and the crashes—piled up. Back problems plagued him, and he feared what could happen if he kept driving. In a 2015 New York Times profile, he said, “If I would race longer, am I going to be walking around on crutches or in a wheelchair?” He was a relatively new father who wanted more time with his kids, so he closed out his NASCAR career in 2015. He remains the third-winningest driver in NASCAR history.

Athletes from many sports routinely leave the playing field, slap on a tailored suit, and enter the broadcast booth, but success is far from assured. Gordon, again, took to his new commentator role as if he’d been doing it his entire life. “He was a natural,” veteran anchor Mike Joy told me, “with an uncanny knack for knowing what the viewer wanted explained. He could describe the action on the track and the broader strategies playing out.”

Joy also witnessed a less publicized side of Gordon. “He wasn’t selfish. He made sure that everyone around him succeeded in the broadcast.”

But after six years at the microphone, Gordon’s competitive spirit resurfaced. “I wanted to contribute more to Hendrick,” he says, “and I realized I could only do that if I was here full time.” At the end of the 2021 season, Gordon left his gig at Fox Sports.

Riding in a car—even a bulky Suburban—with Gordon is a bit surreal, like watching Picasso paint. As he wheels the big Chevy through the access lanes and parking lots of the Hendrick campus, he rattles off the effects of the new NASCAR races on Hendrick’s balance sheet. The Next Gen car did make things more equal, but it cost much more to run than expected. Plus, the car had an Achilles’ heel, a rear suspension piece that broke like a twig and would then sideline the car. “The damn toe link!” Gordon says with a groan.

That is just one of the concerns facing the sport. The biggest issue in the NASCAR garage is the upcoming TV contract. The current $2.4 billion arrangement expires at the end of 2024. So much has changed since that deal was inked in 2013: teams are now organized under a charter system that is similar to the franchise setups of other sports leagues; streaming and social media have upended viewer behavior; teams want a larger share of the TV money to offset rising costs and declining sponsorship revenue. This is the maelstrom Gordon jumped into.

Money is a forever issue in racing, as it buys speed. NASCAR is experimenting with format and venue, too. Last year, the series held a race in the Los Angeles Coliseum, and the schedule now includes one race on a dirt-covered track.

“I love what we did at the Coliseum, but that was an investment and not a profit margin area for us,” says the driver-turned-executive watching the books.

Ever humble, Gordon calls his new role a utility infielder. “It’s very complicated,” he admits. “We want to come together with NASCAR and make the sport bigger than it’s ever been.”

With Gordon’s “wide-windshield” vision, Hendrick—and NASCAR—are in very capable hands.

Nice mini-bio piece on Gordon!