The Grand National Roadster Show is nirvana for devotees of rods and customs. This past weekend, the historic Fairplex in Pomona, California, was packed with everything from tasty highboys and throwback track roadsters to aggressively stanced restomod muscle cars, and lowriders sporting more bling than the Grammys’ green room.

Hot rodding isn’t only about flash and cash. In its earliest incarnation, the hobby focused on transforming humdrum transportation into one-of-kind high-performance vehicles, and the Roadster Show paid homage to these motorsports roots. Three race cars at Pomona caught my eye because they represented three different takes on the hot rod experience.

The first was a chopped and channeled ’34 Ford five-window coupe with “Flat Trap Racing” graphics on the doors, holes cut into a sheet-metal grill that reminded me of a medieval shield, and a roof rippling with dozens of hand-formed louvers.

“I put it together as a street-strip car that you could drive to the track,” owner Cedric Meeks of Portland, Oregon, told me. He’s already dragged it on the sand in New Jersey, on the dirt in Northern California and on the pavement in nearby Riverside. “I’ll take it anywhere to race,” he said.

Meeks is the son of Russ Meeks, whose flip-top, rear-engine 1930 Ford won the 1972 America’s Most Beautiful Roadster award—which is basically the Best Picture Oscar of hot rodding. With that kind of heritage, a cookie-cutter ride wasn’t for him.

“The car had a 327 Chevy with an automatic in it when I got it, but I wanted something different,” he said. So he replaced the ubiquitous small-block with a 235-cubic-inch Hi Torque Chevy straight six with roller cams and a rare Wayne racing head and mated it to four-speed transmission and a quick-change rear end. Sweet.

Across the show floor, I found another unexpected engine that piqued my curiosity. A few years ago, while running a restoration/fabrication shop in Czechoslovakia, Stanley Chavik got his hands on a Buick straight-eight. This inspired him to re-create the Buick-powered Indy car that Phil Shafer built and raced in the 1930s, when the so-called Junk Formula allowed pioneering hot rodders to run stock-block engines at the Speedway. When I asked Chavik why he embarked on such a quixotic build, he laughed. “To beat the Bugattis,” he said.

Chavik shaped the hefty steel frame rails in his press brake and shaped the novel, upright two-man aluminum body by hand. Students of pre-war American production cars might recognize the radiator shell. “It’s a 1933 Pontiac grille—except that I made it myself because I couldn’t find one,” he said. He finished the car in 2016, first raced it in 2017 and brought it to the States when he moved his shop to Orange, California, in 2018.

Amazingly, the car is street legal, and Chavik is happy to drive it anywhere except in the snow, where the tall, narrow, untreaded tires produce about zero grip. Still, when Southern California Timing Associations official turned a blind eye during an event at El Mirage, he got the Buick up to 120 miles per hour on the dry lake. “It was easy,” he insisted. “Driving this thing on the highway—that’s hard.”

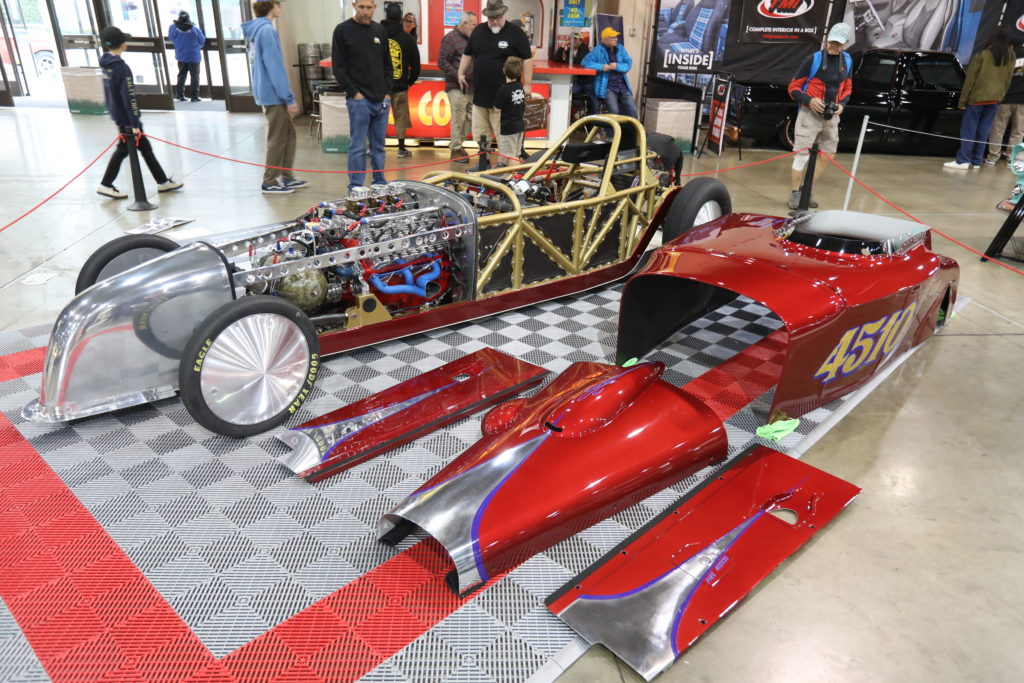

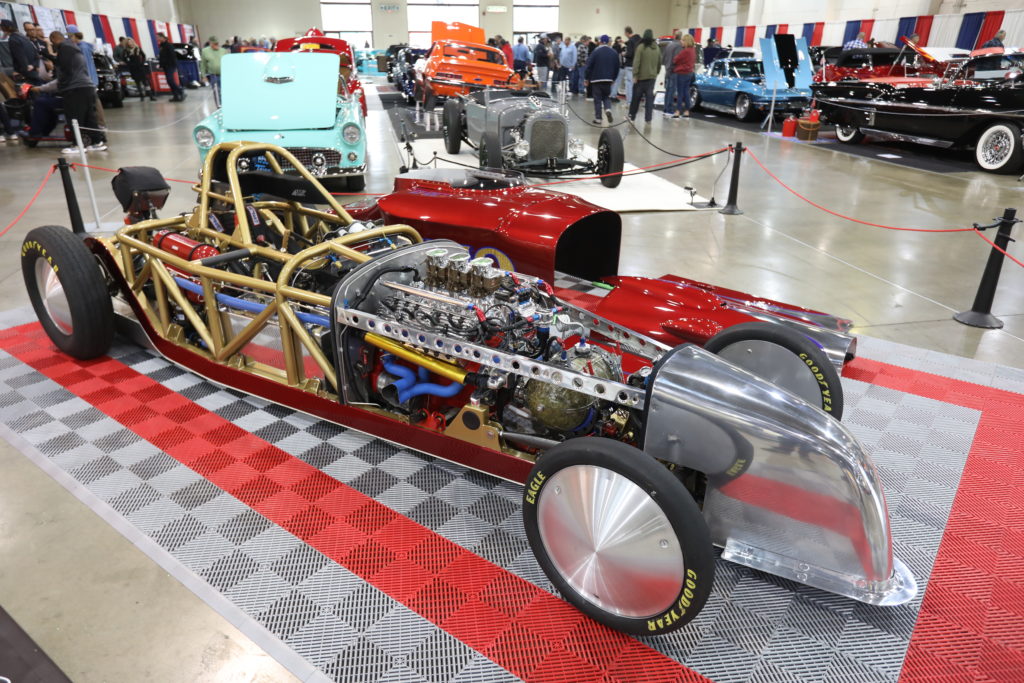

Fast-forwarding nearly a century and through dozens of technological revolutions brought me to Speed Demon, the wicked Bonneville streamliner renowned as the fastest piston-powered, wheel-driven car on the planet. When I’ve seen the car on the salt, with the fearless George Poteet strapped inside the cockpit, the car looked like a missile.

Here at Pomona, it was displayed with the bodywork off, and I was amazed by how tightly the LS-based motor, twin turbos and transmission were packaged within a spider’s web of chromoly tubing.

Here at Pomona, it was displayed with the bodywork off, and I was amazed by how tightly the LS-based motor, twin turbos and transmission were packaged within a spider’s web of chromoly tubing.

“There’s no book that tells you how to build these things,” builder/crew chief Steve Watt explained. “We have a great team of problem solvers. The car sits in the middle of our shop [in Ventura, California], and we walk past it 365 days a year.”

Land-speed cars have been setting records at Bonneville since a trio of thrill-seeking Brits—Malcolm Campbell, George Eyston and John Cobb—set marks there in the 1930s. It was the first SCTA meet in 1949 that started a legacy on the salt flats. Over time, Bonneville became the hod rod racing mecca.

Poteet and Watt have been taking Speed Demon to Bonneville since 2010, when they established a baseline speed of 404.562 miles per hour. Since then, they’ve made incremental gains year after year until topping out at 481.576 in 2020. Watt said the team has been working on some tweaks for their next assault on the salt, during the SCTA’s Speed Week in August.

“If we can get anything over 500, we’re good,” Watt told me. “Then George will be done, and we’ll slow it down from there. There are so many things that can go wrong and so many things that have to go right. It’s eventually going to catch up with you. I don’t care how good you are. If you keep tapping on that window, eventually it’s going to break.”

Exhibit A can be found on YouTube, where there’s in-car video of Poteet barrel-rolling an earlier version of Speed Demon at 370 miles per hour. (The mangled chassis now supports a show car.) Miraculously, Poteet walked away from the wreck.

Of course, nobody ever got hurt bench racing, and that’s all we were doing in Pomona. Plus, we could get Pink’s chili dogs at a nearby concession stand. All you get out on the salt is a sunburn.

Check out some of the other speed demons—including a street-legal Lola—on display at the annual custom show.