“Why am I awake this early on a weekend in August?”

I asked myself this question as I walked from my apartment to the pitch-black parking lot. I knew the answer but that didn’t ease the pain of abandoning my bed before sunrise. Tired and bleary-eyed, I was on a mission north to Auto City Speedway—a small oval track just outside Flint, Michigan—for a weekend of drifting and debauchery.

Mentally committing to attend this drift meet was the easy part. With an enticing name like Hoodstock, I was hooked months in advance. The event’s Facebook page promised a three-day festival of camping, live music, and good grub, using no fewer than three exclamation points (!!!) in the advertisement.

Photos: Chris Stark

I’ve been obsessed with drifting for a while, now, especially at the grassroots level. While I don’t have a proper drift car at the moment, I still engage in the community from the sidelines by photographing friends and competitors. At Hoodstock, I walked away even more amazed than usual at the number of weekend warriors and fans who devote their disposable income and free time to drifting.

My humble abode for the weekend.

For the most authentic experience, I elected to camp each night in a tent rather than rent a hotel room. I must’ve been overly focused on packing for these evenings, because I forgot to bring a hat and water bottle—an unfortunate oversight for a weekend outside in early August.

On my way to the track, I made a pit stop at the gas station. Freshly clad in a cheap cowboy hat and with a case of bottled water in hand, I noticed a fresh-faced teen pull up to the pump next to me. His multi-colored SN95 Mustang was low and loud.

“I’m surprised it made it here,” said the kid. “The rear end is going out.” He drove his New Edge pony to the Flint area from over an hour away—an impressive feat considering his front splitter could scrape chewing gum from pavement. I was tempted to stick around and watch how he navigated the station’s steep driveway.

Once at the track, I strolled around the venue to get the lay of the land. Plenty of other attendees were also roughing it with the bare essentials. The New Edge guy from the gas station made it with a small tent, basic tool kit, and as many spare tires as he could fit inside his Mustang. Others opted for a more robust approach, practically glamping with enclosed trailers, generator-powered televisions, multi-speaker sound systems, and pneumatic tire changers.

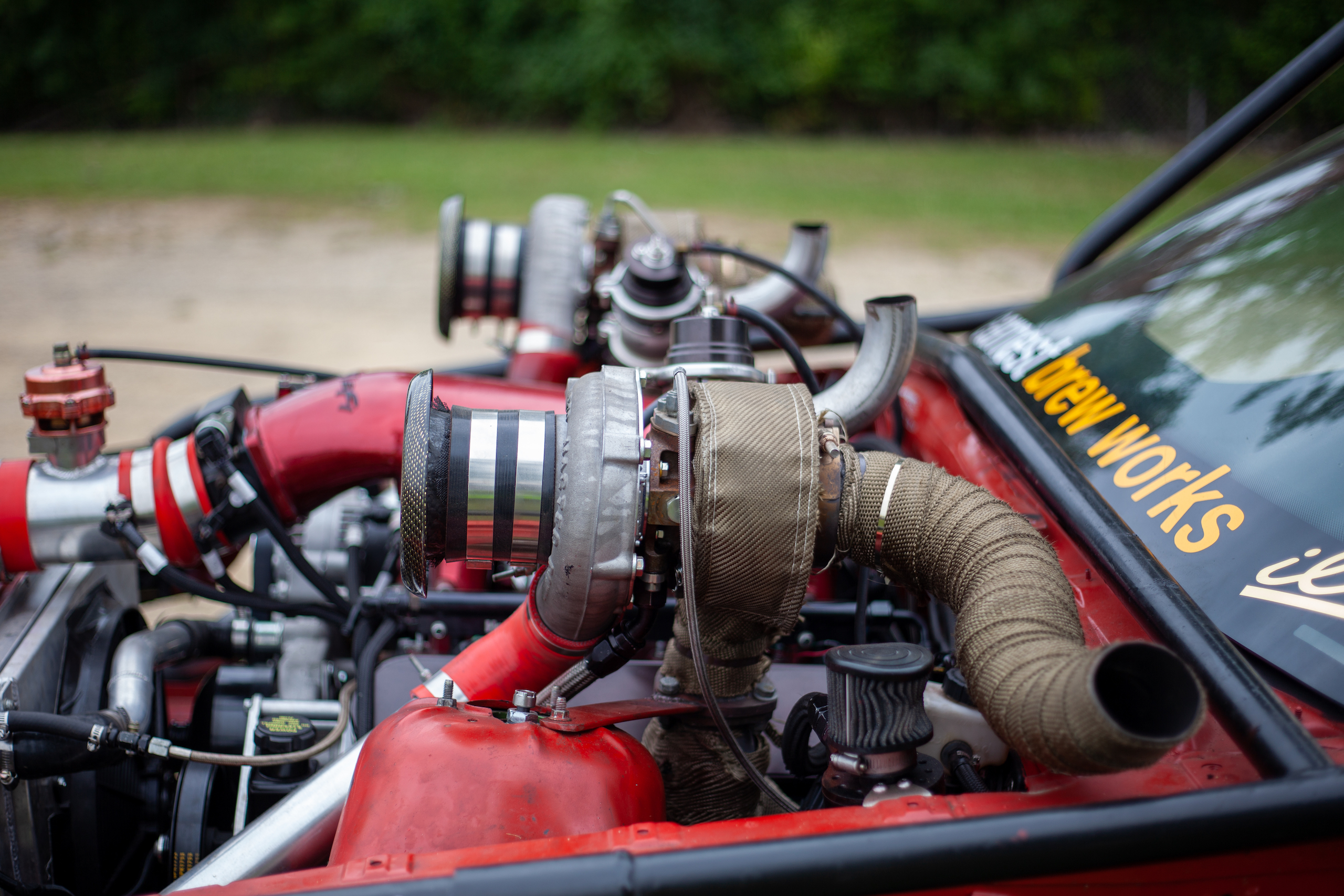

Rad rides littered the paddock, including several unique builds that stood out from the usual crop of Mazdas, Nissans, and Toyotas. Hidden Motorsports—a Toledo tuning shop—showcased an absurdly modified BMW 3 Series which it converted to showcase a panel-free exoskeleton. Powered by a twin-turbo LS-series V-8 and equipped with horn-like exhaust pipes, the Bimmer was rumored to make over 1000 horsepower.

Then there was the ratty Chevy C1500 owned by Ben Symons. From the Mexican blanket-covered bench seat to the Nardi steering wheel, this drift truck exuded eclectic style. Mismatched body panels still wore junkyard markings. “People think my truck’s look is intentional,” he said as he hammered the truck’s hood to release its latch, “but it really is just a beater. And it doesn’t drive good.”

After surveying the pits, I scoped out the track for prime photo locations. Auto City Speedway is a half-mile oval track that primarily caters to late-model stock car racing. Notably, the banked turns have no walls, just a steep grassy decline at the asphalt’s edge. For Hoodstock’s course, the drifters run both banked turns at full chat before meandering through the infield access roads. The lack of guard rails may work for stock cars, but for newbies learning the track—and veteran drivers purposely pushing the boundaries of tire adhesion—it has the potential to cause problems.

Each day brought twelve-plus hours of non-stop drifting—a kind of yaw-heavy endurance event. Tire smoke, unmuffled engines, and sideways driving were givens, but unlike other drift events I have frequented, drivers weren’t in a hurry to get on track. Ample track time and tire conservation factored into the formula, giving the whole event a casual, relaxed feel. I’m not sure any other discipline presents this amount of seat time for weekend racers.

Thirty-six hours of drifting does, however, lead to a high rate of component failure and attrition. Intense heat and lack of air conditioning has a way of wearing on drivers, which leads to mistakes on track. Broken suspension arms, snapped axles, and thrown connecting rods were commonplace.

A school-bus yellow Nissan 350Z, owned by one of the event organizers, boiled its brakes when entering the final banked turn. The doomed Nissan flew over the banking and hurled itself down the grassy hill toward my position on grid. Luckily, the driver regained control of his Z and avoided a collision. The car and driver were fine, but it was a close call. I imagine many extra undergarments back in the camping area were called into service.

Another Z pilot was not so lucky. He totaling his car after sailing over the first banked turn and crashing into the track’s property fence.

When track went cold each night, drivers fixed their broken cars and prepared for the next day of drifting. Others broke out red Solo cups, or multitasked by enjoying libations between turning wrenches. On Saturday, the driver of a V-8-powered Nissan 240SX grenaded his transmission. In order to mate the replacement gearbox to the engine, he spent most of the night cutting the bell housing to make room for the adapter kit. He and his friends laughed and joked as they took slices to hot metal. Hoodstock’s clatter of cordless tools and intense partying lingered until four in the morning.

My head felt like the Nissan’s transmission by Sunday morning. Still, it was a weekend well-spent soaking in the smoky spectacle and enjoying time with friends both new and old. I had set out to better understand why grassroots drifters throw so much money and time at this particular flavor of motorsport. The abundant seat time—compared to, say, autocross—is part of the allure. But I think it’s the community at an event like Hoodstock that keeps people coming back. Symons summed it up most succinctly: “I was driving something ridiculous, and I got to see a bunch of people I hadn’t seen in a while.”

Simple, right? Just that is enough lure us clowns out of bed before daybreak.