The blue and white 1965 Plymouth Barracuda on the grid at this year’s Goodwood Revival blatted out Talladega riffs from its side-pipes and looked as menacing as any car possibly can while sitting in the second-to-last starting spot. At the wheel was The Blackadder himself, Rowan Atkinson, perhaps best known to Americans as the ridiculous Mr. Bean, while hidden inside the rear brake drum was a kluge that I helped install to try to get the car through the race without its rear brakes failing. Did Atkinson know that he was about to trust his life to a borrowed throttle return spring, some aircraft safety wire, and the ring off a delivery van keychain? Mmm … don’t think so.

Sometimes you get pulled into things. Or, in my case, you stand around long enough trying not to look like a complete idiot that you fall into things. I stood around Duncan Pittaway’s Barracuda as Subaru’s guest at this year’s Goodwood Revival, the famous British race meet and vintage dress-up gala, so long that eventually I sort of became part of the crew.

Aaron Robinson

I had known Pittaway exactly four days, having earlier stopped in at his shop in Bristol, England where he keeps the Barracuda as well as numerous other old cars, the most famous of which is the Beast of Turin. It’s a flame-spitting 1910 Fiat land-speed-record car with a 28-liter four-cylinder that has connecting rods the size of sledgehammers. The 120-mph car is YouTube-famous, and I was there to (hopefully) get a ride and a story. But Pittaway was too busy trying to prep the Barracuda for Goodwood and his star co-driver, Atkinson, that he had no time for flame-spitting, so that story will have to wait.

I liked Pittaway instantly. He came out of his shop with grease on his arms and a tie around his neck. He said his grandfather told him never to leave the house without one on and he’s always followed that rule. Anybody who wears a necktie in his shop has my admiration. Pittaway is also hysterically droll, like when he says to a fellow he’s known for ten minutes, “You know, you’re a lot nicer than everybody says.”

Aaron Robinson

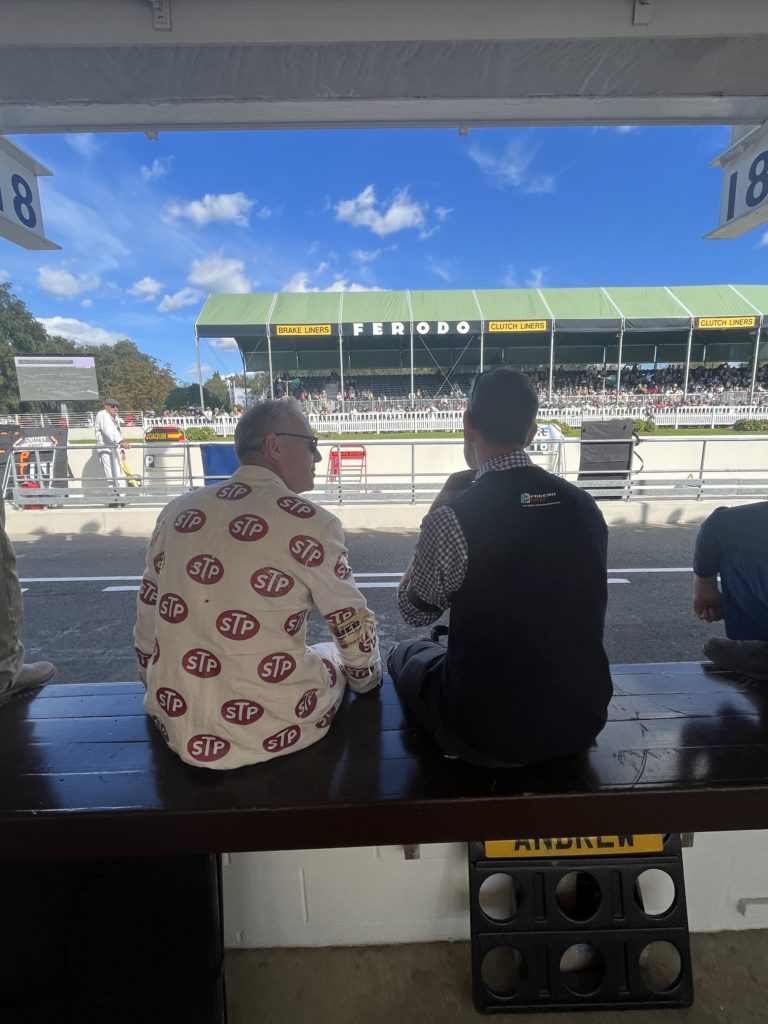

He wasn’t hard to track down at the Revival. Amid all the 1940s frocks and fedoras and mustachioed men wearing RAF group captain uniforms, both the Barracuda and Pittaway, dressed in a white suit covered ankle-to-shoulders in STP logos (a nod to the late, great Andy Granatelli) were like an In-N-Out burger planted in the center of London’s Barkly Square. I told Pittaway that, as an American, the Granatelli getup straight-up put a lump in my throat. He said I was the only person so far who had gotten the reference. Then he invited me to have a cup of tea, and that’s it. I just stood around the Barracuda for the next couple of days trying to be useful.

Mainly I helped push the car around, and I carried tools to the pit wall. I also cleaned out a lot of dirty teacups. After Atkinson drove the Cuda on the event’s first day, he reported transmission noise and soft brakes. It was decided the transmission was probably fine, so attention turned to the brakes. Pittaway’s longtime friend, Jon Payne, who joined McLaren in the 1990s as a composites specialist while it was still building the famous F1 road car, was the Barracuda’s sole mechanic, and I became his semi-able assistant.

With the drums disassembled, one thing became obvious. The shoe linings were worn down to paper in places. Pittaway Racing, which (I don’t think he’ll mind me saying) will never be confused with Team Red Bull, had accidentally left the spare brake shoes in Bristol. So the issue became how to get the rear brakes through the weekend.

- Aaron Robinson

- Aaron Robinson

Another related problem was that of the three factory brake-return springs fitted to the Mopar’s drums, the lower spring on one side had been replaced at some point. It was a spindly little spring, possibly off a Morris Minor, and it looked totally inadequate for the big Cuda’s shoes. Thus, they likely weren’t retracting from the drums fully when the brake pedal was released, which may help explain why the pads were down to almost nothing.

A couple of guys in our class were racing big Ford Galaxie 500s, but they had no spare springs from which we could fashion a substitute. Though any NAPA in America probably has them or something like them, Mopar drum-brake springs from the 1960s are a rather hard thing to come by in southern England. Payne and I began to walk the paddock, and we didn’t get far before he spotted someone he knew, a crewman for a team running a 1965 Lola-Chevorlet T70. That gentleman produced two stout throttle-return springs from his box, and we went with those.

Aaron Robinson

The springs had double-rolled loops at the end, meaning you attach them the same way you attach a key to a keyring: by lifting one end of the wire with your fingernail and sliding the thing you want to attach around in circles until its joined. That wouldn’t work for fitting it to the Mopar’s brake shoe. So Payne came up with the idea of using a steel key ring off the rather bulky and many-ringed keychain for his Mercedes van as the attachment point for the shoe. At the other end, he would safety-wire the spring to the opposite shoe, thus making it possible to draw tension on the spring once the shoes were fitted up by pulling on the wire and twisting it.

I have to say, it looked pretty good as we wiped the brake soot off our hands.

Aaron Robinson

Atkinson was next up to drive. Okay, so, maybe his life wasn’t exactly in danger, but a worst-case scenario could be imagined where a chunk of the lining failed and then swirled around inside the drum to shear off what remained of the other brake lining just at a critical moment, causing the Barracuda to pinwheel off the track. I’ve seen drum brakes fail that way, though in that case the car didn’t crash, it just started making a hideous metal-on-metal noise from the back. We tried not to think about that possibility as the Atkinson roared off the line.

As it happened, the Cuda ran fine though it was slow. The mildly worked 318 V-8 just didn’t have enough ponies to overcome the Plymouth’s weight and its wind-scooping profile against the quicker and lighter Alfas and Ford Cortinas in the class. Atkinson, a Goodwood veteran, finished pretty much where he started, in the back. But over tea and with a huge crowd gathered around the Cuda pining for photos and autographs (Mr. Bean is obviously a much bigger deal in Britain than America), he pronounced the car fine and fun. He had a good time.

Atkinson then turned to Pittaway and whispered, “Who’s that foreign chap?”

- Aaron Robinson

- Aaron Robinson

- Aaron Robinson

- Aaron Robinson

- Aaron Robinson

- Aaron Robinson

- Aaron Robinson

- Aaron Robinson

- Aaron Robinson

- Aaron Robinson

It sure looks like a 1966 Plymouth Barracuda. The 318 LA didn’t appear until 1967.

Great story and good fun.

What a cool looking Barracuda. Maybe next time a 340 or 360?

Believe that’s a 66 Front end on the Barracuda. 64/65 had identical grilles, 66 was a change.

The tail lights are ’66 as well, but who cares?