It was eight o’clock on a Saturday night in central Indiana. The late summer sun was setting behind the backstretch, and clouds of bugs were already gathering in bright stadium lights. Local racer Mark Tunny was about to fold himself into the cockpit of a winged modified machine and battle 43 other weekend warriors in a three-hour figure-8 race at the Indianapolis Speedrome.

About 15 miles east of The Brickyard, the old track resembles a flat parking lot. Girdled by aluminum grandstands filled to the brim with figure-8 fanatics, the fifth-mile oval has served as the site for the epic endurance race since 1977. If you’re not familiar with the format, it’s about the same as a door-banging circle track race, but rather than running the course’s oval perimeter, combatants turn into the paved infield and drive through a crossover. And every September, the discipline’s top talent pass through this intersection for three hours straight, risking everything for a shot at a 10-foot-tall trophy, a decent paycheck, and—above all—bragging rights as winner of the World Figure-8 Championship.

No other series, apart from maybe a destruction derby, can actually promise contact, and the fact that something this inherently dangerous exists in the face of this modern-era’s extreme caution is truly enticing. There’s a reason why you don’t see Sunday racers dipping down to the grassroots level to run a figure-8 race, though I imagine plenty of fans would like to see them try.

The annual race is figure-8’s version of the Indy 500 that happens across town. Even a decent showing in the lesser-known Indianapolis tradition will initiate you into the figure-8 fraternity. Since 2003, the Tunny family has won the race 12 times, with Bruce Tunny landing the first blow. In 2022, his son Mark was poised to continue the family’s two-decade reign and clinch his third victory in the heralded race. “I feel like the second was almost more special,” he said. “You don’t feel like a one-hit wonder.” Already zipped to the chin in purple Nomex, he gave no indication of nerves, and answered my questions with the patience of a university professor.

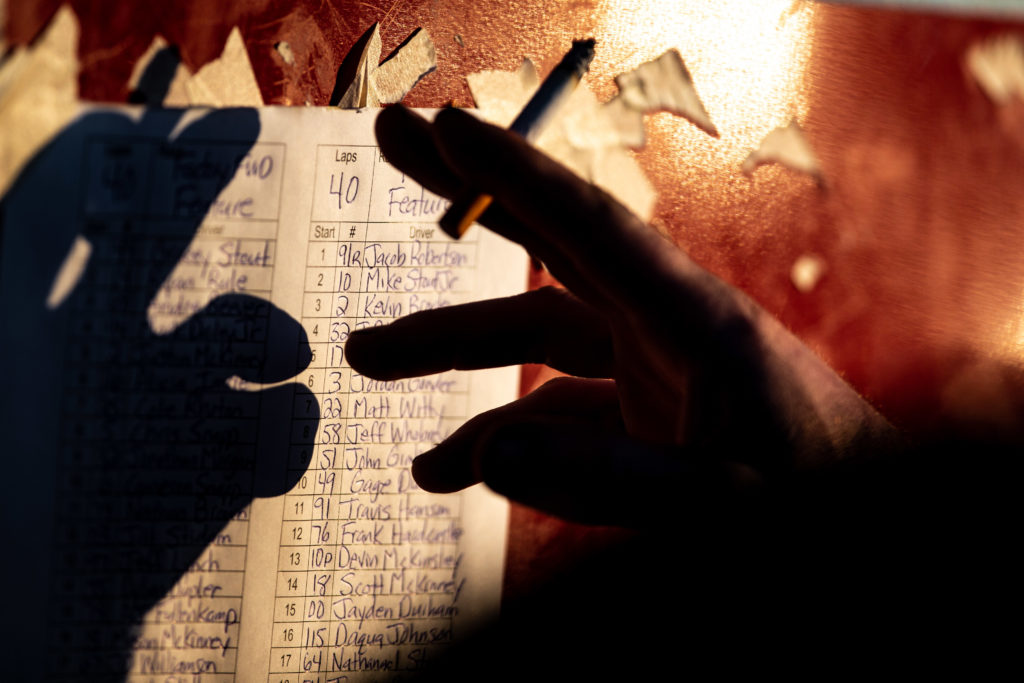

- Mark Tunny earns pole position during qualifying.

- Drivers battle in front of a sold-out crowd.

Tunny’s tranquility was a surprise, considering that over the next few hours—if the 37-year-old was lucky—he would pass through an intersection filled with smoke, debris, and cross-traffic some 900 times.

Indeed, the figure-8 racing presents the world’s fastest intersection with no street signs. “You have to find your holes last second,” said Tunny. On average, about 10 incidents of “light contact” and three “big ones” take place during the three-hour race.

“There’s nothing mentally, physically, emotionally, that could prepare you for something like that,” said Craig VandeWettering, another driver on the grid. “Last year, they had to pull me from the car after the race was over.” Making the tow from Minnesota, VandeWettering is one of three entrants not from Indiana or Kentucky. And he almost didn’t make the starting lineup, eking in during the last few minutes of qualifying.

Even if you don’t qualify for the race on lap time, your weekend isn’t over. Alternates who don’t make the show cycle into the race during cautions, and until attrition takes enough of a toll, there are consistently over two dozen cars packed into the tight bullring. “You’re happy when you see friends go out because it’s one less car you have to deal with,” said VandeWettering.

The Minnesota man, along with the rest of the field, strapped in. As a local starlet belted the National Anthem, one of the drivers tucked a pack of cigarettes and lighter into a square-shaped metal box near the rollbar.

“It’s a long race,” he said.

The field of winged racers, lead by Mark Tunny and his cousin Ben on the front row, stampeded under the fluttering green flag, and a timer on the jumbotron started its countdown from three hours.

During the first hour, you should try to stay on the lead lap. Or, at least that’s the general consensus from the pros. This is, of course, easier said than done. Less than two minutes in, and leader Mark Tunny was already dragging the brake to avoid t-boning backmarkers.

Unlike other motorsports, which typically ratchet up tension as the race progresses, the World Championship race is nail-biting all the way through. Just five minutes in, the conveyor belt of cars was weaving through the intersection like a troop of choreographed dancers. Anxiety: pegged.

“You have to run in packs,” explained Steve “the Bull” Durham. “If you get to a crossover and you’re just one car against something like seven cars, they’re not going to stop for you.” Durham, like the rest of the drivers, has a full-time job outside of racing. When he’s not rushing the intersection, he works construction and owns his own lawn care business.

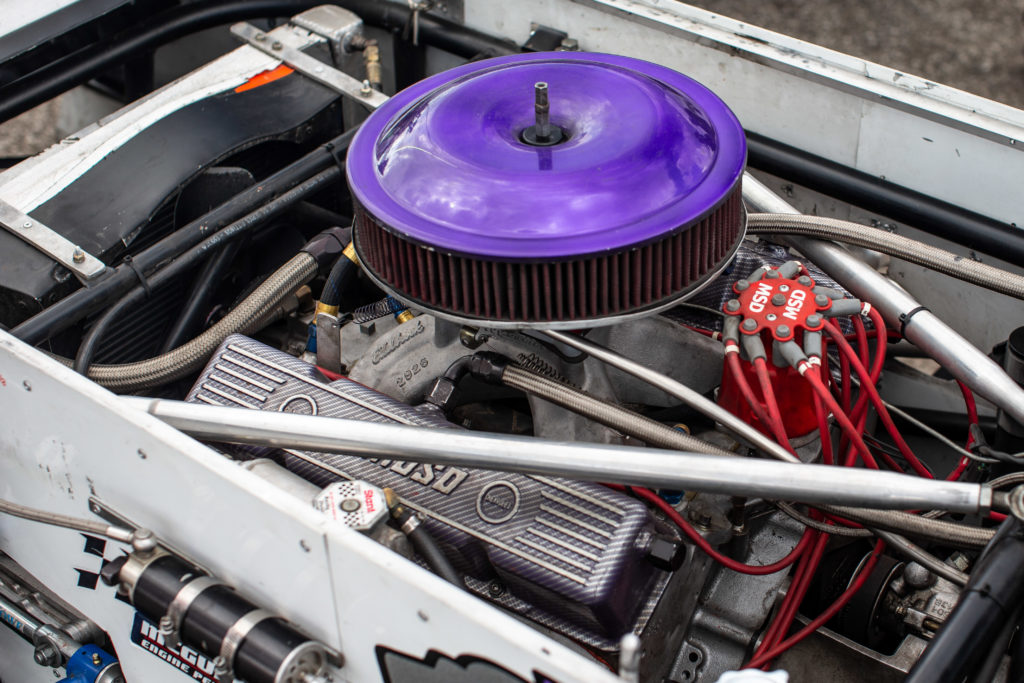

A 20-year veteran of the big figure-8 race, he knows the rulebook like a favorite song. Though, from the sound of it, the book is pretty thin. “They’re pretty lenient on rules,” he said. “You get the weight, the wings, and spoiler set, you’re good.” Back in the day, top-tier fugure-8 cars were largely late model production cars such as second-gen Camaros or Mustangs. Now, a majority of the cars are built by one of the five chassis manufacturers. There isn’t a motor rule, though most teams opt for the tried-and-true small block Chevy. And some slide the engine so far back that they have to mount it at an angle so that the driveshaft can clear the driver’s legs. Inside, drivers can adjust brake bias and shock damping during the race via dials.

The Bull also explained that you might want to weld an extra bumper hoop on, but you should avoid making it a battleship as the added weight will slow you down. “If you can survive this race, there’s a big race in Colorado.” I think he meant the car, but I couldn’t be sure.

- Jesse Tunny punches the brakes to avoid punting cousin Mark.

- Crews make frequent adjustments—and fixes—during the weekend

Back on track, and the Bull was holding his own inside the top ten. Tunny was still out front, but he hadn’t put any distance on the rest of the field, though. And the intersection now more closely resembled the clouds of bugs that swarmed in the lights above.

To fly through the crossover is one-part premeditation, one-part luck. Some drivers try to time an opening, while others like Doodle Harris say, “Oh, hell with it,” flinging their 2500-pound contraptions through the intersection. I asked him how he navigated the treacherous crossroads, expecting some insider knowledge from the crowd favorite. He looked at me plainly and, in a drawl straight-from-Louisville, he said, “You just go’on through there.”

Regardless of method, Doodle, The Bull, along with The Marksman, Mr. Excitement, The Outlaw, and the rest of the figure-8 contingent were zooming through the crossover without incident. In fact, much of the calamity occurred in the corners. Tunny pointed out that sometimes drivers will become hyper-focused on the intersection and cause a wreck in the corner as a result of their break in concentration.

Just over halfway through the contest and the intersection hosted its first “big one.” A four-car smash caused the crowd to erupt. During the pause in action select drivers ducked into the pits outside of the cramped track for service. Unlike most short track affairs, the pit stops are live, and every minute spent in the dimly-lit paddock are precious positions on track. Crew members, cousins, moms, and sisters hop in with headlamps and impact wrenches.

Mark Tunny relinquished the lead during a round of stops but was back out front by lap 300. As the countdown fell under twenty minutes, a light sprinkle fell over the speedway. As if racing through an intersection twice per lap wasn’t stressful enough, drivers had to contend with rain on their visor and a potentially slick surface.

471 laps in, Tunny crossed the line as the clock ticked to zero, earning his third victory in the historic race. If his second victory ranked higher than his first, I wondered how he felt about his third. After all, the triumph tied him in the record books with his father, and car builder, Bruce. On cue, he laid a thick burnout down the backstretch. (If there were any bugs in the lights, they were gone now thanks to the Hoosier-supplied smoke out.) He created a similar plume on the front stretch and then jumped on the roof of his car, fist pumping all the way through.

In victory lane, he was no longer the serene driver I had spoke to before the race. “You look at the list of 3-Hour winners,” he said, sweat dripping from his brow,” they’d wax anybody’s a** in NASCAR.” Drivers, the gauntlet has been laid.