Crazy race track, crazy car, and a crazy driver. In 2003, I experienced what remains the wildest ride of my life, charging fill-tilt around the Nürburgring, in a car called a Radical SR3 Turbo. We were there to break the lap record for a road-legal car. The driver was Phil Bennett, one-time driver from the British Touring Car Championship and nutcase of some repute.

Bennett, driving solo and on his first lap in the car, lapped in seven minutes and 19 seconds, which convincingly broke the existing lap record. Soon after I sat next to him for a passenger ride. I can’t remember the exact time for that lap but it wasn’t much slower than his record setter. I like to think of myself as being fairly brave, but when I stepped out of the Radical after the lap, I was completely white and could barely stand I was shaking so much.

Nineteen years later and Radical has just celebrated its 25th birthday. Radical Sportscars was started in 1997 by amateur racers and engineers Phil Abbott and Mick Hyde, who wanted to build a racing car that could be affordable yet highly competitive. The result was the Radical 1100 Clubsport, powered by a Kawasaki motorcycle engine. As often happens, other racers were impressed by the cars’ performance and wanted their own Radicals. Eventually, enough 1100 Clubsports were sold to make it worthwhile for a one-make series.

Abbott and Hyde, who are no longer involved in the company, could never have imagined that a quarter of a century later Radical Sportscars would build its 3000th car, or that there are now 33 dealers in 21 countries around the world. And just as amazing, there are 14 Radical race series spread around the world from Europe to America and to the Philippines. There’s even one in the Bahamas. What could be better than a racing series in the Caribbean? Sign me up.

Radical’s factory is in Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, where it was founded in ’97. Photos: Barry Hayden

When Bennett broke the Nürburgring lap record there was a subsequent brouhaha about whether the car could be considered road legal. The fact that I’d driven the car on the public roads in Germany to get us to a lunch of currywurst—and to also fill it with fuel—was not deemed good enough. Subsequently, when Radical Sportscars went back to the iconic circuit to establish another record with its more powerful SR8, the company drove the car from its factory in Peterborough to the Nürburgring to emphatically make the point.

Despite its international reach, Radical Sportscars is still based in Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, on the same industrial estate where it was founded in 1997. It has the same postcode, but a much bigger footprint these days. Although I have driven many Radicals over the years, this is my first visit to the factory that builds them. I wasn’t expecting works on such a grand scale.

The guide for our visit is James Scott, head of engineering. Like the majority of the 110 employees at Radical, Scott is remarkably young. The average age of the workers is 29 which is great news for the future. Also Radical has an apprenticeship scheme which this year has seen half a dozen youngsters learning their trade at 24-26 Ivatt Way, Peterborough – an initiative worth applauding.

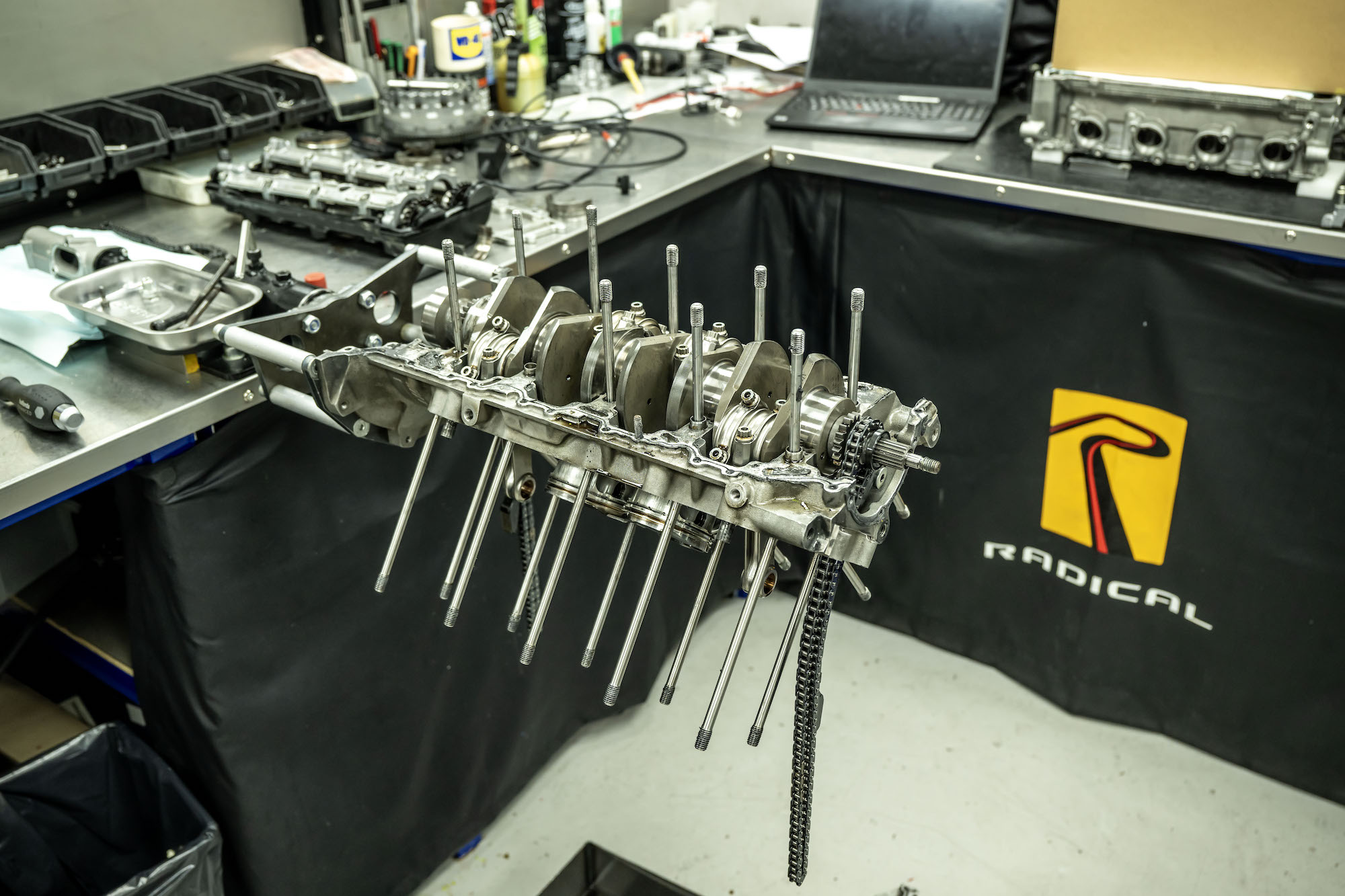

Our first stop touring the factory is the engine shop, which is technically a subsidiary called Radical Precision Engineering. Radical currently builds three different models (a fourth is on its way but more of that later) which are the entry-level SR1, then the SR3 and finally the top of the range SR10. Both the SR1 and SR3 are powered by Suzuki Hayabusa four-cylinder motorcycle engines. Bikers will know that the Hayabusa engine is not only incredibly powerful, but also extremely strong—not bad for cars that are driven hard for most of their miles.

Ant Phillips, engine shop supervisor, explains the difference between the engines used in the SR1 and SR3: “The SR1 uses the Hayabusa engine in its standard form which means a displacement of 1340cc and a power output of 182bhp. We convert the engine to dry sump lubrication because the cornering forces in the car would drive the oil up on side of the sump and starve the engine of oil. The Hayabusa engine in the SR3 is substantially modified. The engine is stroked out to 1500cc, Arrow connecting rods are fitted and the head is gas flowed. This gives us 226 horsepower.”

“The SR10 is powered by a Ford engine. It’s the same unit that’s used in the four-cylinder Mustang and also the Focus ST,” explains Phillips. “We also convert the Ford engine to dry sump lubrication and also fit a larger Garrett turbocharger, Cosworth pistons and blueprint the engine so that in this form it produces 425 horsepower.”

Also sitting on benches in the workshop are a few very special engines. These are custom-made V8 motors built using Hayabusa cylinder heads and barrels, bolted to a bespoke cast aluminum crankcase. Built in various different specifications over the years with power outputs from 380 horsepower and beyond, it is this homespun V8 that powered the SR8 that, in 2009, set the Nurburgring lap time mentioned earlier. It is a wonderfully compact engine that gave the Radical SR8 performance that rivaled Le Mans Prototypes. The engines in the shop today are all in for rebuilds.

Next, Scott ushered us to the area where the chassis are built. You might expect to see sheets of carbon fibre cloth and an autoclave but Radicals are built using a tubular steel chassis, as they’ve always been. “Our goal has always been to produce affordable racing cars that are easy to maintain and also to repair. In most racing accidents a corner will be wiped off requiring new wishbones to be fitted, but occasionally the chassis itself will be damaged. Once the car has been stripped down the chassis can be returned to us and the bent tubes cut out and replaced. Or this can be done in the customer’s own country at a race shop. The trouble with carbon fibre tubs is that they’re expensive to produce in the first place and hard to repair.”

I didn’t expect to see lines of chassis constructed on jigs because it’s more common for companies like Radical to sub contract out chassis manufacture (to companies like Arch Motors in Huntingdon who for years produced Caterham chassis and the distinctive tube frames for Ariel Atoms). Radical does as much as possible under its own roof.

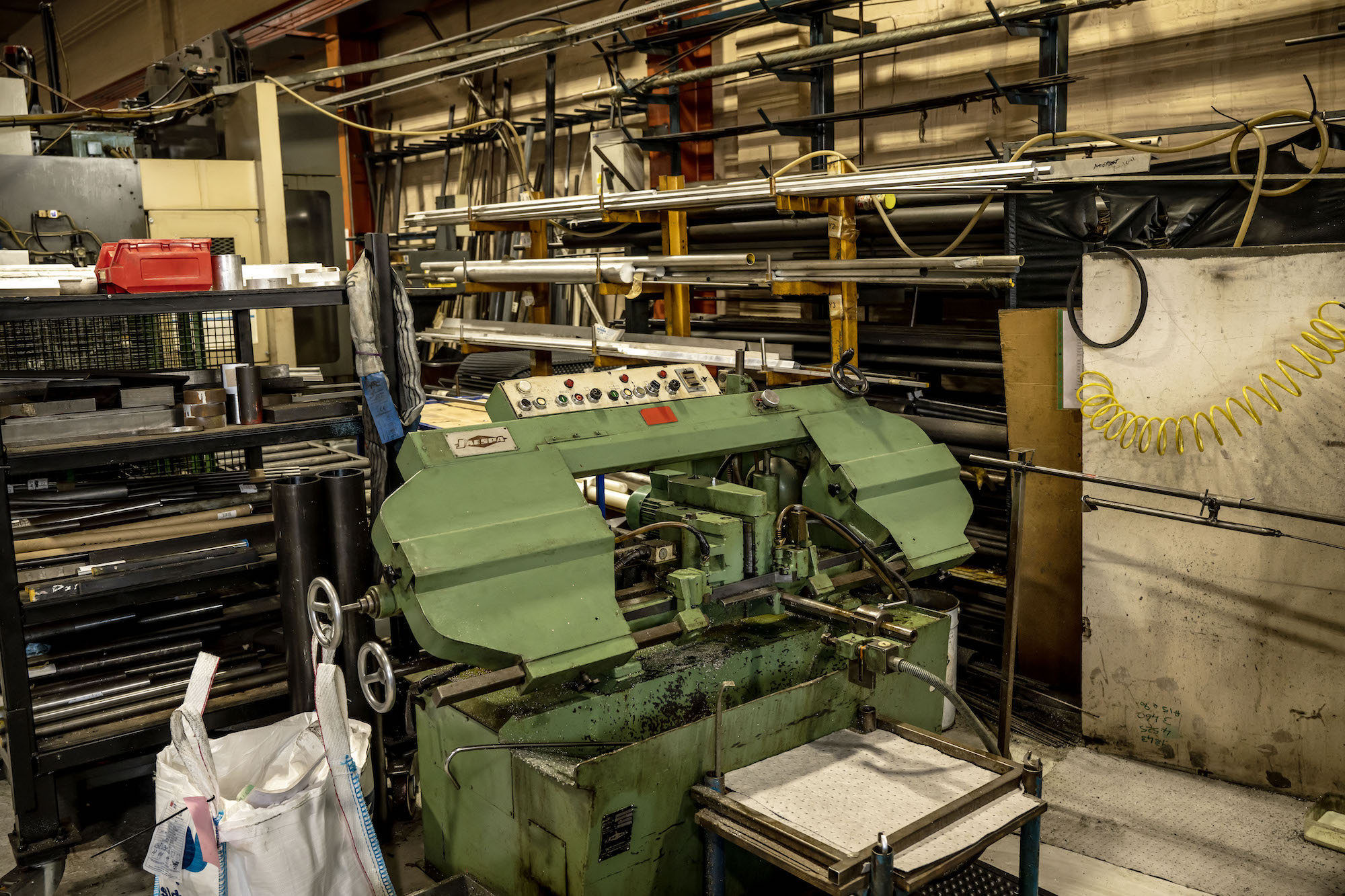

“We’ve always built our own chassis,” says Scott. “It gives us a lot of flexibility and control.” This said, many of the tubes for the chassis are produced by outside companies who prepare the tubes by bending or notching (also known as fishmouthing) them ready for assembly by MIG welding by Radical’s craftspeople. The finished chassis are then sent to a local company for powder coating before returning to Radical for fitting out. That process not only involves fitting wiring harnesses, suspension, powertrain and other assemblies, but also honeycomb crush structure panels and strengthening panels that are pop-riveted to the chassis tubes.

“Radical Sportscars has always had a policy of making as much of the car in-house as possible,” explains Scott, “which is particularly advantageous in these times of supply issues. This year we will have built 197 cars and that’s a record for us.”

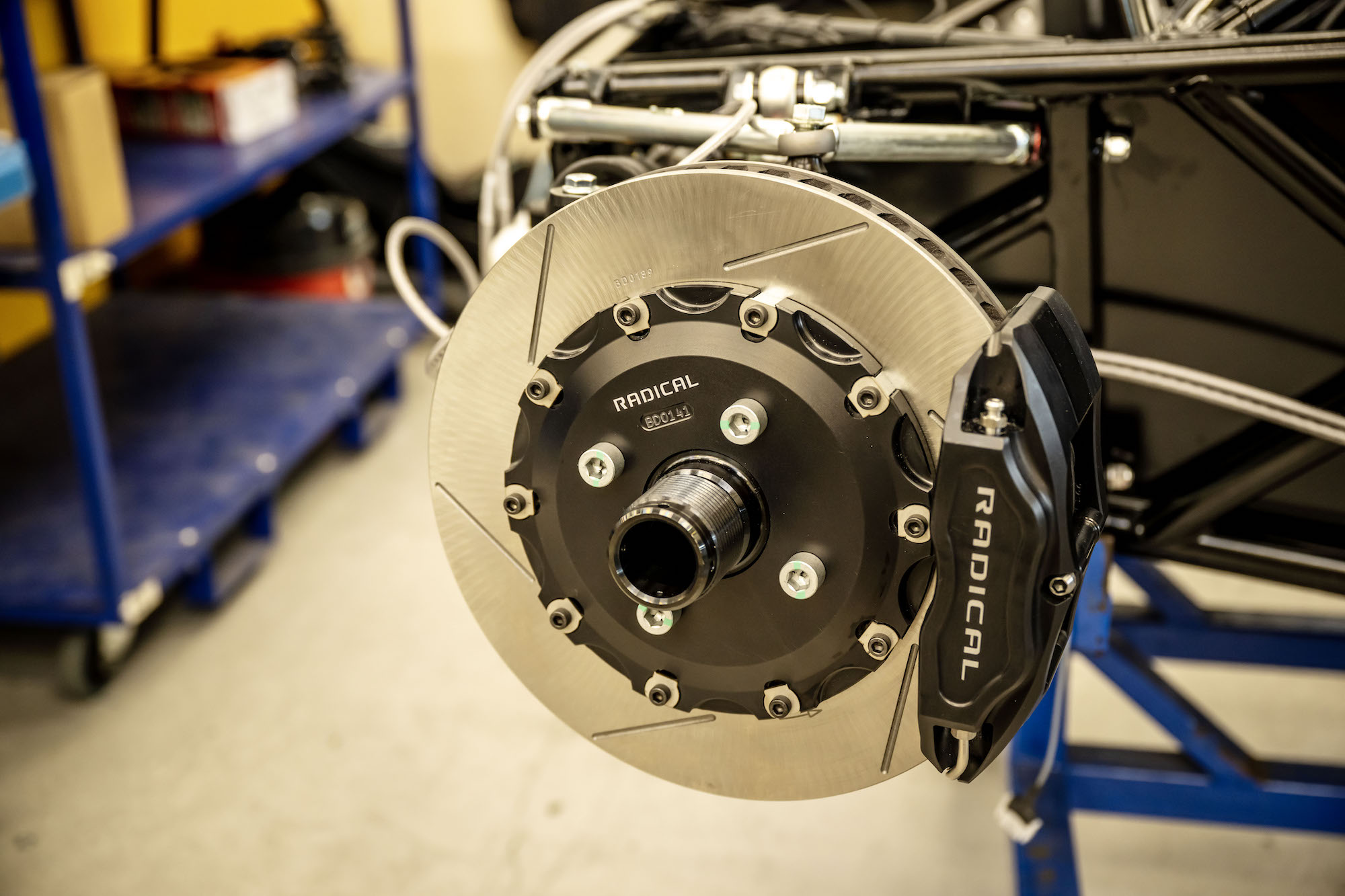

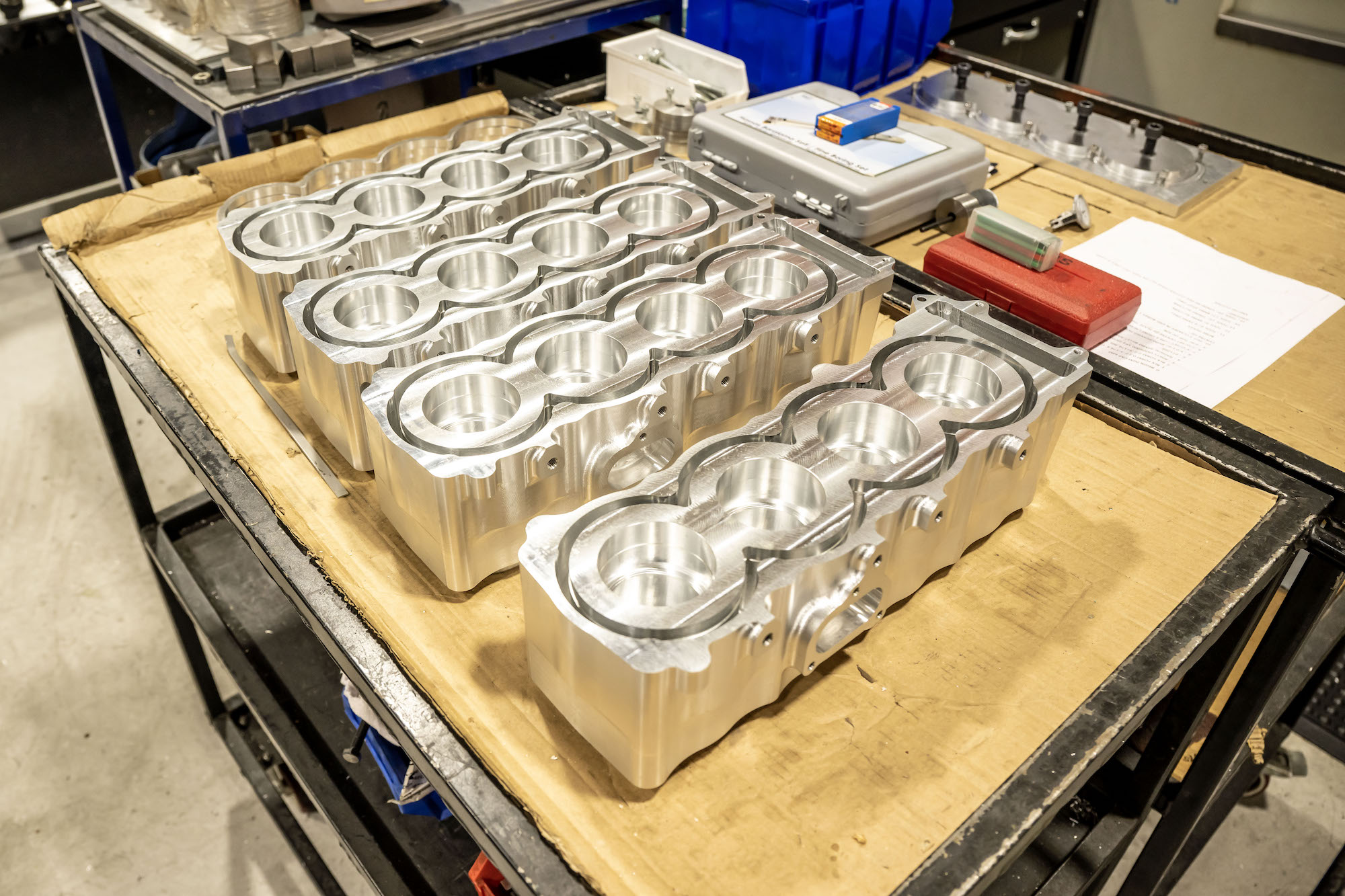

Banks of CNC machines turn blank castings into shiny new components such as hubs, uprights and even bellmouths for intake systems. Scott apologized for the lack of glamour, polish and shine in the factory, but the products that are made here speak for themselves. You don’t need a flashy premises to produce high quality products.

Not everyone in the company is a youngster. In the pattern making shop a couple of experienced craftsmen are planing and shaping patterns from which molds will be taken, which will then be used to make production components. Most of the cars’s bodywork is made from fiberglass, including the large one-piece front ends.

Again, this is in the interest of cost saving that’s passed onto the customer. “Not only is carbon fibre expensive to produce in the first place, it’s complicated to repair. The front body section of an SR1 costs around $850 which is pretty reasonable and keeps the cost of racing the cars down. Of course, repairing fiberglass is pretty straightforward and minor damage can even be repaired track side.” Some components are made from carbon fiber, however, and in the past one-off bodies have been made from the material. Typically Radical’s composites shop will make 30% more body panels than the number needed for actual cars so that there are plenty of replacements.

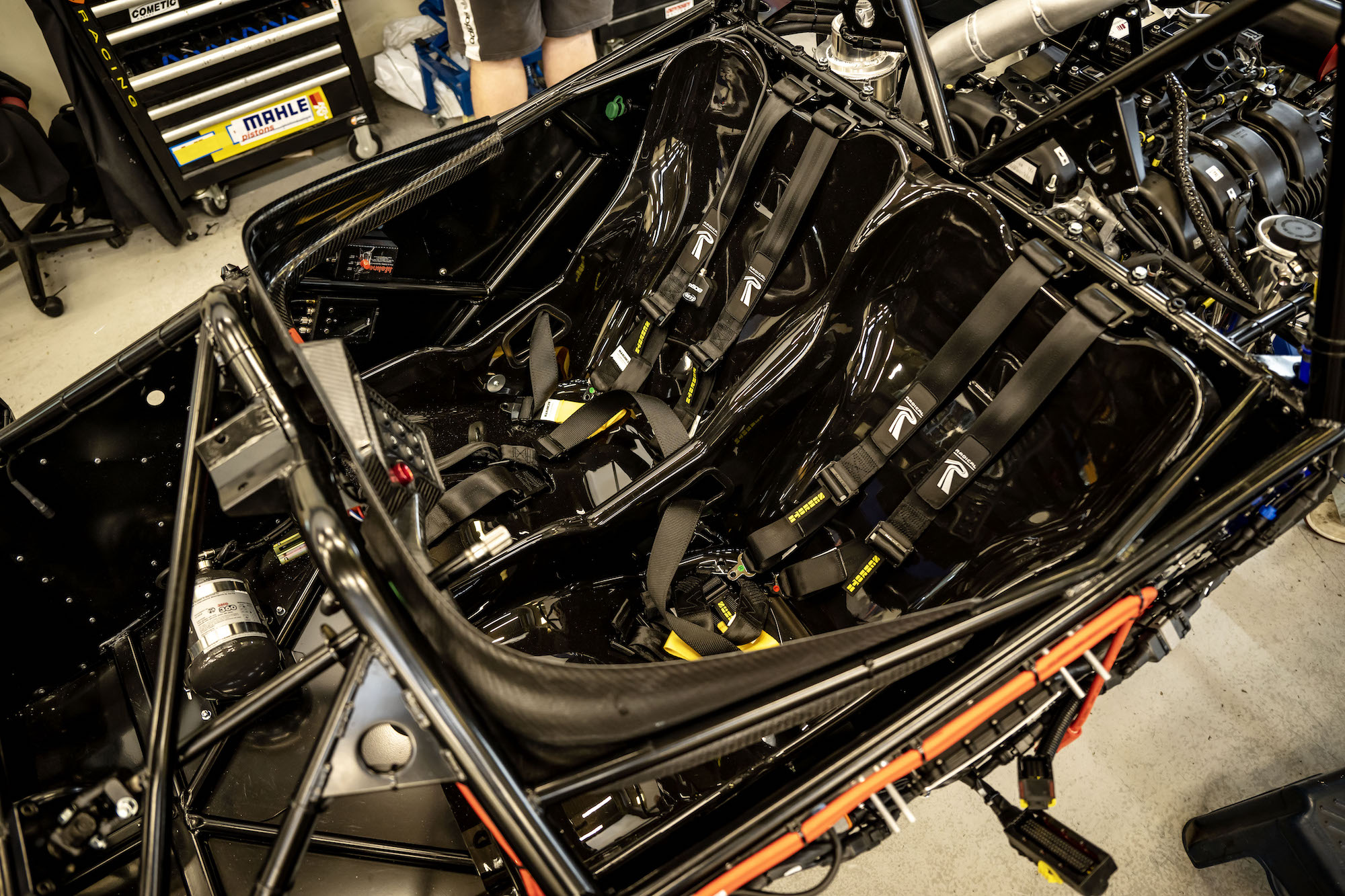

It’s in the final assembly area that you get to see the real depth of quality in a Radical. There is no production line, each car is assembled by a couple of technicians who know every aspect of the car and how it goes together. The SR1 might be the entry-level model, but like its brothers, it bristles with top quality components. It’s an impressive package for about $57,000. Even the SR10 at $153,500 represents pretty good value when you look at the performance that you’re getting.

There were some secret parts in the pattern shop earlier that we weren’t allowed to photograph. No doubt they’re for the limited edition ‘Project 25’ that Radical will be producing next year as a celebration of the company’s quarter century. Only 25 will be built and the coupé will be powered by a 3.0-liter turbo V6 that will produce 850 horsepower. Radical has produced several closed cockpit cars in the past, badged as the RXC 600R and RXC GT3, and there are few of them in the assembly shop. My lottery winnings would be spent on a coupé; they’re so small and compact, like a smaller Porsche 956.

Radical Sportscars’ timing was immaculate. The launch of the company in 1997 coincided with the increase in popularity in track days and many who fall in love with circuit driving at such events often turn to racing for the extra thrill that competition brings with it. The beauty of racing a car like the Radical is not just that you get incredible performance and impressive, British-built quality for your money, but also that you will be racing in a spec class. A large organization, and an even larger community, all for one crazy car.

***