Among the circle track ranks, the NASCAR Cup Series is widely regarded as the top of the heap. The 74-year-old stock cars series is home to the biggest teams, largest purses, and most lucrative contracts. To arrive in Cup is to reach an unfathomable plateau, joining the elite ranks of those who make a living turning left, while others clamor for breaks below your feet.

You might assume, then, that NASCAR’s prolific stock car series also houses the fastest circle track racers in the country. After all, top-tier stick-and-ball teams always outperform the minor leagues.

In NASCAR’s case, that couldn’t be further from the reality. There is an abundance of semi-professional and grassroots race cars that could outperform a Next Gen stocker if entered in a heads-up one-lap race. The trouble is that NASCAR rarely races on the same tracks as motorsport’s weekend warriors, preventing any opportunity to really showcase the discrepancy in laps times between NASCAR and a “lesser” discipline.

One of these rare opportunities arose last week when the World of Outlaws sprint car series rolled into one of NASCAR’s legacy tracks, Bristol Motor Speedway. For the second year in a row, Bristol’s bigwigs decided to leave the temporary dirt surface—utilized for the spring Cup Series race—on their half-mile oval for an additional week, to host America’s fastest sprint cars. By racing on the same track, fans would witness a rare control in which to compare the two series.

Before we dive into lap times and average speeds, let’s review the technical differences between stock and sprint cars. NASCAR’s Next Gen car produces a 670 horsepower from a naturally aspirated V-8 and weighs approximately 3200 pounds. For Bristol’s dirt race—the Cup Series’ only foray on the clay—Goodyear supplies wide, slightly staggered (taller right sides) grooved dirt tires.

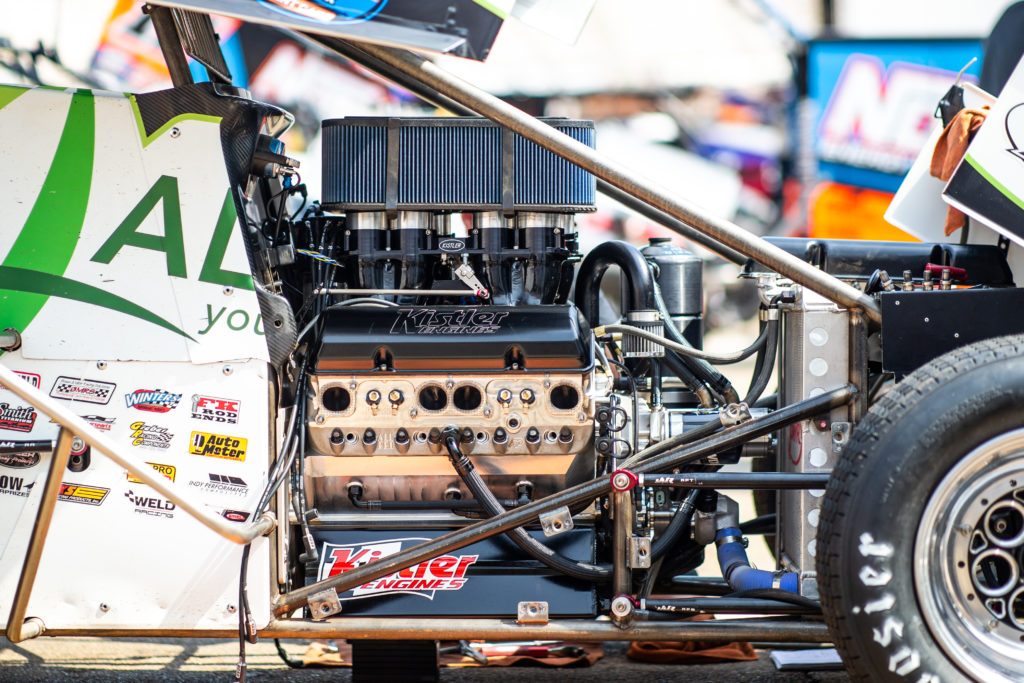

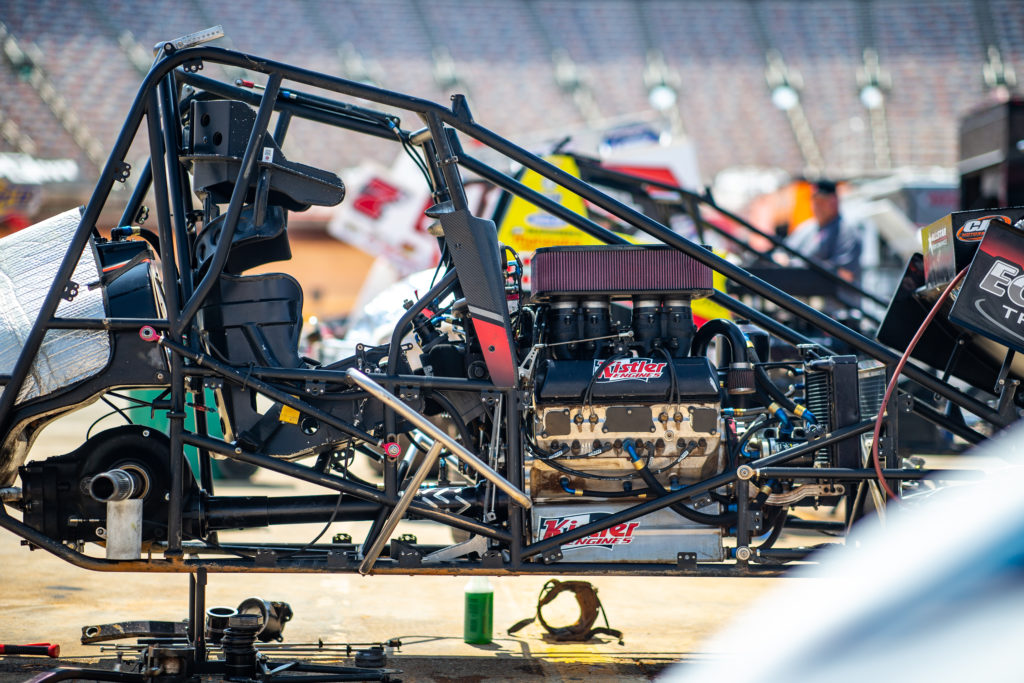

A World of Outlaws sprint car cranks out upwards of 900 horsepower from a naturally aspirated 401-cubic inch V-8 and weighs 1400 pounds. Sprints ride on similarly-grooved Hoosier tires, but the disparity in stagger from left side to right, is far greater. Unlike a Cup car, you can visually see the stagger in a sprint’s tire setup. The right rear, in fact, is one of the largest tires in all of circle track racing. These vehicles also feature two giant airfoils that create massive amounts of side force for drivers to lean against in the corners.

In short, sprints are purpose-built machines, with the sole purpose of going fast on dirt. And Bristol is the fastest track that the Outlaws face in their 90-race season. “The banking and the way that it sucks you into the corner is greater than we feel at any other track across the country,” said Connecticut driver David Gravel.

So, how fast did the Outlaws go?

In the first night of sprint car racing, Pennsylvania’s Logan Schuchart ripped-off a pole-winning lap of 13.83 seconds, which was orders of magnitude quicker than the 20-second laps turned by NASCAR’s best drivers earlier that month—nearly a seven-second delta over a half-mile distance. The stockers averaged 90 mph around the track, whereas sprint drivers, aboard their winged rockets, were averaging 138 mph around the clay-covered bullring. To put that in perspective, Formula 1 cars lapping at Silverstone—one of F1’s fastest circuits—average 140 mph.

With these high speeds, the dirt had to be perfect. Any rut, pothole, or imperfection in the surface could likely send a car flipping like a samara seed in the wind. To keep the dirt track in prime condition throughout the weekend, Bristol employed a water truck to keep the surface tacky and a fleet of Crown Victorias to pack the circuit.

Given Bristol’s high speeds, sprint teams had to modify their machines. “My guys put all new components in our cars and did a few things just make sure that, at high speeds, everything stays together,” says rising star Carson Macedo.

Some groups opted to swap out aluminum suspension components (radius rods) in favor of stronger, steel bits. Braces were also added to the sideboards of their giant airfoils to prevent any sort of collapse from the high side forces. Since the dirt-covered track has roughly 19 degrees of banking in the corners, some teams elected to cut a portion of the right-side wing so that drivers could see out of their right side, even under full load.

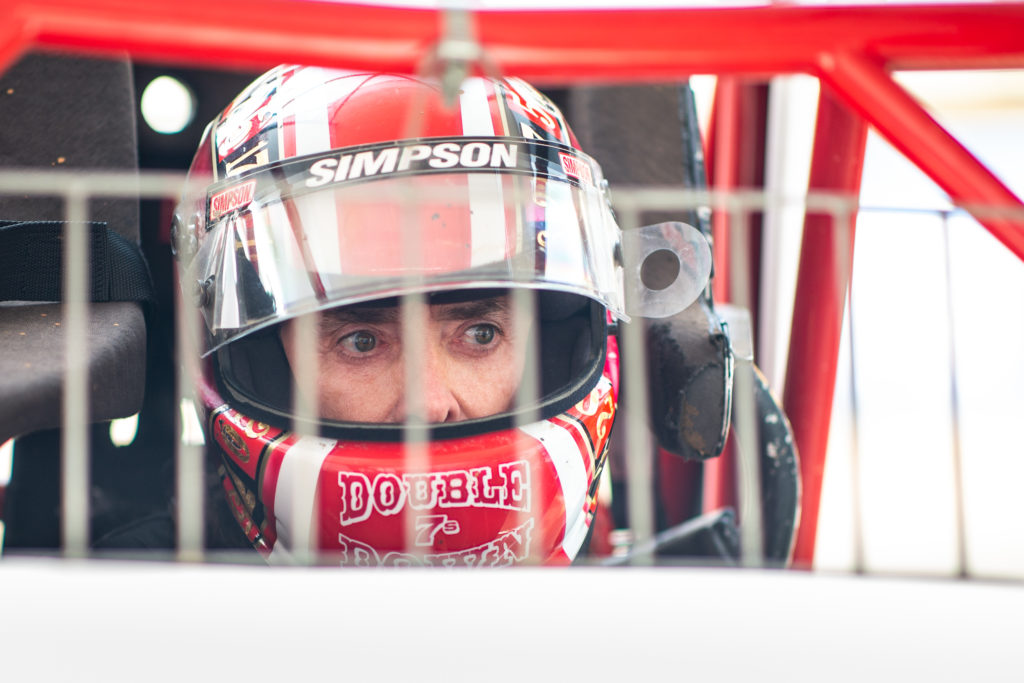

Drivers, like their teams, also had to modify their approach. Typically, sprint racers describing piloting their cars as an “elbows out” affair, meaning they must manhandle the beast around the circuit, much like a riding a bull. At Bristol, it was quite the opposite. Fast times around the high-banked oval came from the smoothest drivers with steady hands. “You have to do everything you can to not scrub speed,” said Outlaw driver Brock Zearfoss. “Times are so close, any speed that you give up is a spot on the track.”

Even those who scrubbed the most speed, throughout the weekend, were still seconds ahead of Cup Series cars on the time charts. NASCAR may be the apex circle track series, but the raw pace of sprints shows that by no means is it the fastest.