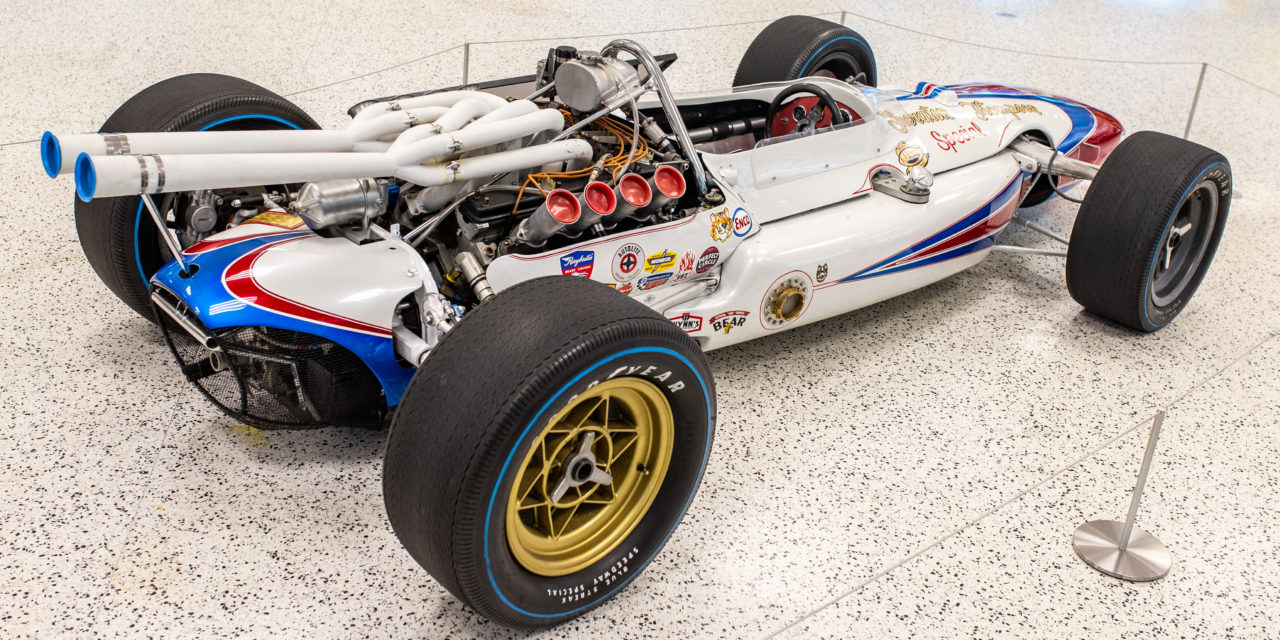

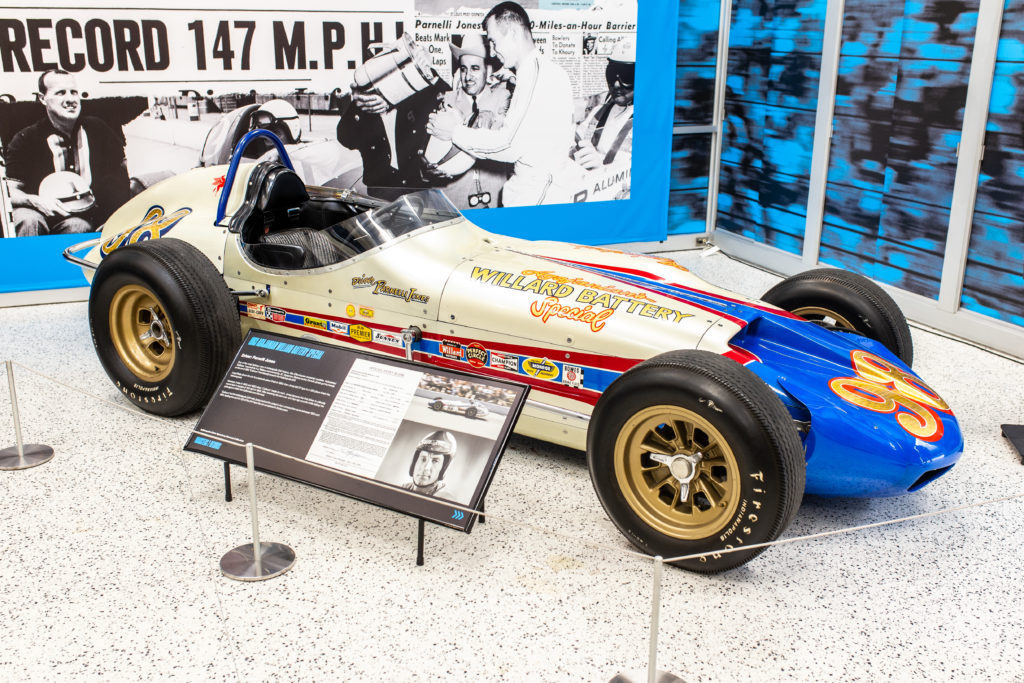

And in 1962, Jones broke the 150 mile-per-hour mark in qualifying, led 120 laps, but succumbed to brake issues in the second half of the race.

It was the 1963 race, though, that immortalized the car—and solidified Jones’ title as a multi-discipline hall-of-fame driver, finding victory lane in sports cars, off-road Broncos, and open wheel. Featuring a few new improvements, Jones was back at the top of the pylon throughout the month of May, and in the closing laps he and old Calhoun held a 43-second lead over Jim Clark in a rear-engine Lotus-Ford.

The four-year-old car hadn’t lost an ounce of pace, but it was losing oil.

While completing the remaining circuits, calls from around the track claimed that Jones’ car was leaking oil from the side-mounted tank. Despite the reports, race organizers USAC never black-flagged the entry. The California driver and his trusty steed cruised to their first 500 triumph.

Calhoun was back in 1964 with Jones at the wheel, but a fire cut the car’s final race short. In its tenure, Calhoun lead the 500 for 321 out of 647 completed circuits.

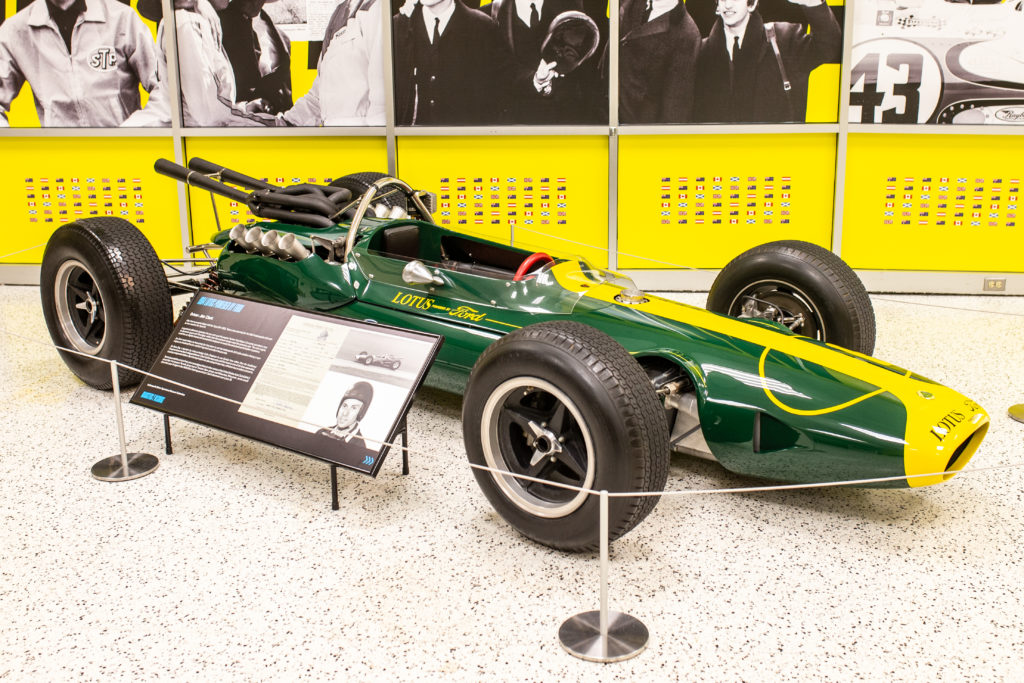

But the onward march of progress heads to no one. The fact that a car was this successful, with minimal changes, over four years underlined how unknowingly stagnant the Indy scene had become. Rear-engine roadsters were a growing dot in the mirrors of the proven Offenhauser-powered Watson roadsters. In fact, just one year after Calhoun’s final bout, a fresh-faced Scottish driver named Jim Clark would bring the rear-engine layout its first win in 1965 aboard a Lotus-Ford, signifying that the revolution had arrived.

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum highlights this era of great change in its latest exhibit, “Roadsters 2 Records.” A period of immense change at the Speedway, from 1960 through the early-1970s is succinctly condensed into two large rooms of the actual cars that brought about these radical changes. I thought I’d share some of my favorites from the collection. If you’d like to see these cars—and so much more, including the helmets, tech, and other Indy innovations throughout the decade—I urge you to pay a visit. The exhibit runs until the first week in November 2022.

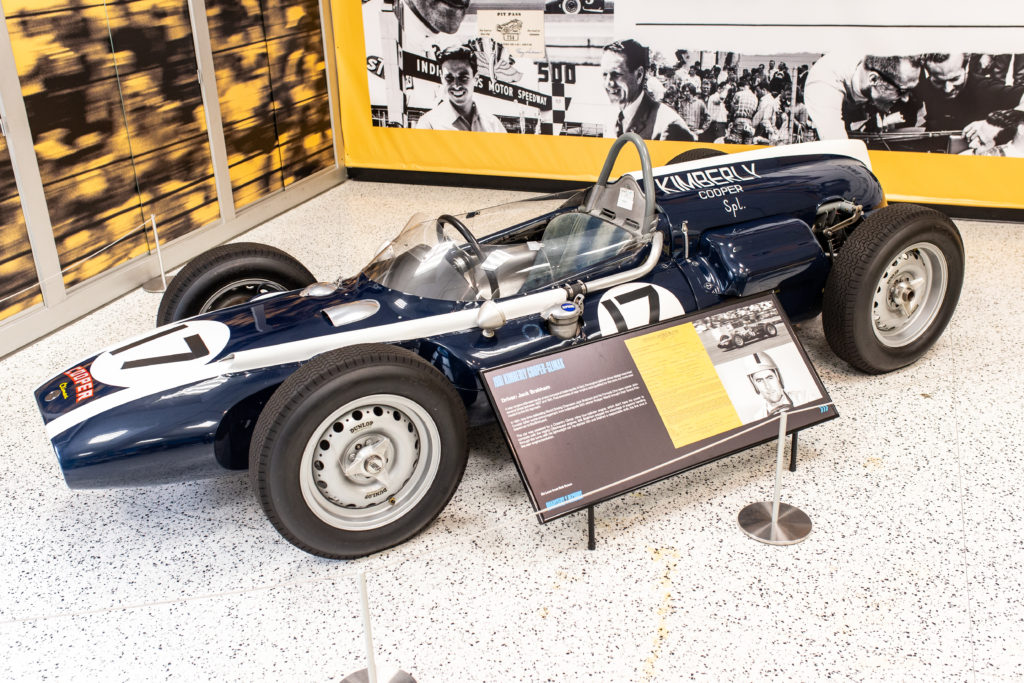

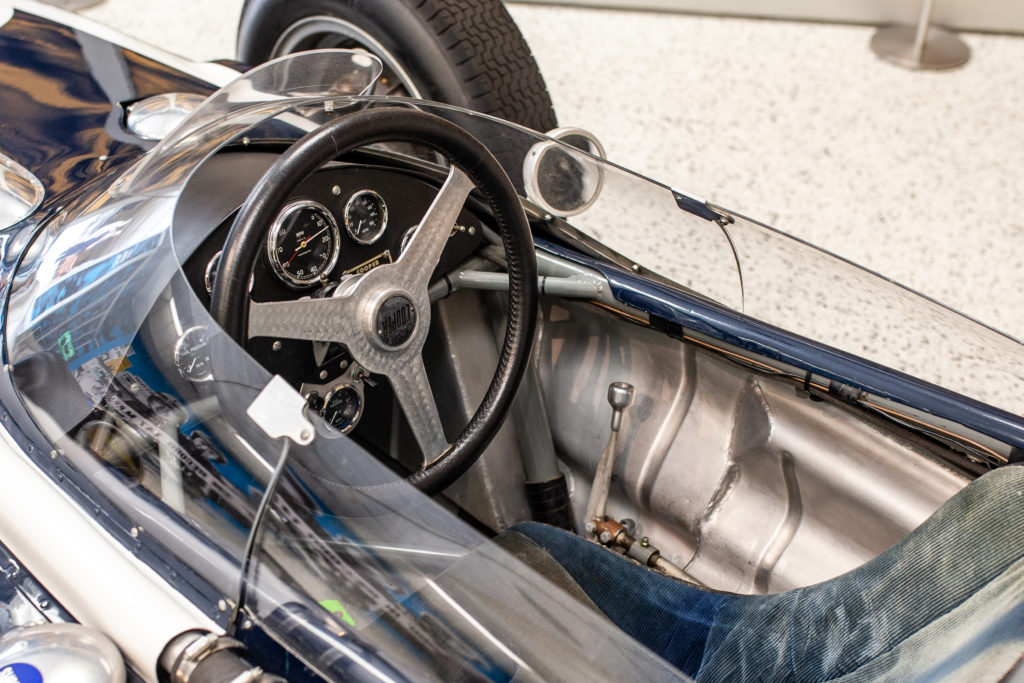

1961 Kimberly Cooper-Climax

Fun party trick: Next time you’re in a room full of Indy fanatics, ask them which car was the first rear-engine roadster to start in the 500. Many may incorrectly guess this Cooper-Climax T54 that ran in 1961. (The first rear-engine to qualify was a Gulf-Miller in 1939, driven by George Bailey. Not that George Bailey.)

While it wasn’t the first—or even the second—rear-engine roadster to roll onto the Indy grid, it was arguably the most important. “The first shot in the the rear-engine revolution,” says its exhibit placard. Driven by Jack Brabham, the royal blue, cigar-shaped racer featured a Coventry Climx inline four-cylinder, which was out-powered by the proven Offenhausers. Still, the machine made excellent pace, made possible by its lightweight configuration. If A.J. Foyt’s winning Watson roadster was a rhino, the Cooper was a lithe butterfly, and one that flew to a respectable ninth-place finish.

1964 Hurst Floor Shift Special

In 1964, one of stock car racing’s most innovative mechanics ditched the fenders and built an open-wheel racer for the Indianapolis 500. Despite the rapid innovation and eclectic mix of front and rear engine roadsters on the 500 grid, absolutely nothing looked like the mad mechanic’s creation. Known as “Smokey’s sidecar,” the car featured an offset pod where the driver sat, gauges mounted by the driver’s forearm, and—the only thing conventional about this rig—a proven 255-cubic inch Offenhauser inline four mounted out back.

Rookie driver Bobby Johns spun the car into the retaining wall during qualifying. Try as they may, the car couldn’t be repaired in time to make another run. The novel racers never saw action again.

1965 Sheraton-Thompson Special

The most successful Lotus in IndyCar history started life as a backup car. The cigar-shaped roadster was another bullet in Team Lotus’ chamber for its 1964 Indy 500 drivers, during the month of May. After a disappointing 500, Team Lotus sold all three of its Type 34s to FoMoCo.

Ford eventually gave the car to A.J. Foyt, after Foyt and Parnelli Jones each piloted the car at undercard events throughout the 1964 season. What a difference a year made. Foyt was hot out of the gate, earning pole positions in each of the first four races, including the 1965 Indy 500. The battle was lost for the front-engine roadsters. Ford’s top two shoes, and the most revered drivers at the speedway, had switched to the rear-engine roadsters.

1968 Pepsi-Frito Lay Special

By 1966, Watson roadsters that had cleaned house the previous decade were quickly becoming antiques—the last one to compete (also on display) ran in ’66. It was clear to owners, mechanics, and drivers that the winning formula at Indy was a rear-mounted engine. Somebody either forgot to tell legend Jim Hurtubise, or, more likely, he just didn’t listen. For the strong-willed driver nicknamed “Herk,” it was likely the latter.

In the display, a photocopied entry form next to the car—which is displayed as it was found—reveals that Hurtubise was the owner, driver, and chief mechanic. The “Mallard,” as he called it, was more of a compromise between the old and the new. Its engine, while still in front of the driver, sat more toward the middle, and the whole car weighed less than 1350 pounds.

Plagued by fuel injection problems in its maiden voyage, the roadster failed to qualify for the 1967 Indy 500. No to be dissuaded, Hurtubise brought the same car back a year later in a rather dapper Pepsi-Frito Lay livery and made it into the show. After nine laps, he suffered an engine failure, ultimately becoming the last front-engine roadster to compete in the 500.

1972 American Marine Underwriters Special

The primary sponsor is ironic if you consider that the whole front half of this 1972 Antares looks like an upside down boat. Jokes, aside the construction of this particular roadster was quite calculated as it was the first Indy car designed on a computer, using “data processed onto punch cards containing long numeric formulas and equations.”

The first of its kind, the Antares also uses a primordial version of ground effects. A rounded bottom uses airflow under the car to create downforce. Team owners Pat Patrick and Lindsey Hopkins were also ahead of their time in their use of onboard telemetry gathered through sensors on the car and sent back to the an engineer in the garage. Despite the three revolutionary advances, which have become best practice in the industry today, the Antares never found success on track and could only ever muster a 24th in the big race.

1972 Sunoco McLaren

In the years following the rear-engine revolution, aerodynamics surfaced as the hottest, most-polarizing topic at the Speedway. Teams scrambled to develop and build new aero features into their cars.

McLaren debuted its M16 in 1971. To workaround USAC’s rule that disallowed bolt-on aero devices, Big Orange shaped a rear wing into the engine cover. The cars were quick from the drop, populating three of the top four starting positions at the ’71 Indy 500.

Roger Penske, most likely taking note of the M16’s instant speed, ordered two M16Bs for the following year. The refined car possessed a shorter nose so that the massive rear wing could fit within USAC’s maximum length rule. Teammates Gary Bettenhausen and Mark Donohue combined to lead a total of 151 of 200 laps, with Donohue leading the final 13 circuits. His marked the first of Penske’s 18 Indy 500 victories as a team owner.