I stood on the apron of the south turn at Winchester Speedway, “The World’s Fastest Half-Mile.” As I moved my gaze skyward, my eyes flashed over the patched and porous pavement. Gouge here. Crack, crater there. After a long scan I finally spotted the concrete crest where white retaining wall met pale blue. I was a bug in a cereal bowl. The sudden fire of a dozen race engines jolted me out of a trance. Still in awe of the immense banking, I retreated to the infield.

Winchester Speedway is the second-oldest purpose built oval in the U.S., built just five years after the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. In 1914, Frank Funk began building a clay, half-mile oval in Randolph County, Indiana, about 90 miles northeast of big Indy. After two years of construction, the track (then called Funk’s Speedway), hosted its first automobile race.

Banking made speed and speed made spectacle, and Funk was a savvy promoter. He consistently added banking to his half-mile oval throughout his early years of ownership, carving clay from the infield and stacking it along the perimeter. Compared to the fairground horse tracks, where most auto racing took place back then, Winchester was a towering monster. By 1932, the corners had reached an unfathomable 45 degrees. (Daytona’s banking tops out at 31 degrees and even the deadly Monza banks were only 21 degrees.) A ride around Winchester at speed was so fierce, in fact, that a local doctor had to frequently dispense drugs to treat drivers experiencing vertigo and intense nausea. Winchester, and two neighboring speedways with similar layouts in Salem and Dayton, were labeled the Hills of Death.

Eventually, Funk sold his speedway. While new owners settled on 37-degree banking and paved the course, the enthusiasm for Winchester endured. Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, open-wheel all-stars and their adoring fans flocked to the track as USAC and other sanctioning bodies became staples on the summer schedule. Midget and sprint racers A.J. Foyt and Parnelli Jones, were followed by Larry Rice and Pancho Carter. Jeff Gordon and Tony Stewart arrived in the 1990s. Forget winning—if you wanted to earn a ride on Sunday, you had to at least survive Winchester.

Today, the path to the upper echelons of motorsport looks mighty different. With karting and open-wheel feeder series exposing novices to road courses rather than harrowing bull rings like Winchester, that kind of crucible is no longer necessary. To remember and properly honor those days gone by, and edify youngsters on the history of the high banks, the Midwest Oldtimers Vintage Race Car Club (MOVRCC) hosts an annual exhibition race at Winchester. Open-wheel rides from the past century carve around the half-mile for an afternoon of nostalgic speed. When the cohort isn’t on track, they park their cars in a caravan on the infield, rendered into a paddock of sorts. Lawn chairs, tents, toolboxes, and hotdogs on the grill—a circle track paradise in the long shadows of Winchester Speedway.

Founded in 1997 by Jack Biddison and Jack Ball, MOVRCC (at over 100 members-strong) has one mission: “Bring the past to the present.” Leading the charge on- and off-track is the duty of club president Jim Channell. Despite his propensity for vintage steel, the Indiana-native has only been in the club for 12 years. After a 2010 visit to Winchester’s sister raceway in Salem—where the MOVRCC also runs—he was inspired to purchase his own old school circle tracker. “I bought a car within a month,” said Channell, “Five hours into owning it, I had the whole history of my midget mapped out.” In less than two years after his visit to Salem, Channell and his Edmunds-style midget were on the track with the rest of his Oldtimer cohorts.

After several years of exhibition, Channell sold his pint-sized open-wheeler to a museum in California and used the cash to purchase a sprint car. The car—built by one-time Vel’s Parnelli Jones Racing crew chief Johnny Capels—is a celebrity on the grassroots circle track scene, highlighted by a cover shot of the car in Open Wheel magazine. Fabricated in 1984, it features a 350 cubic-inch small block, Indy car-style sway bars, and 17-inch wide Hoosier steamrollers. For the meet at Winchester, Channell opted to wear his president hat for the afternoon, so he passed the wheel to pro driver Bob McCombs. “It’s not for the timid,” said McCombs of the vintage sprinter at Winchester. “You better know what the hell you’re doing or you’re going to eat the wall.” From the elevated infield in turn three, spectators could spot the top of his helmet, as he careened down into the turn lap after lap.

Over two dozen other vintage cars joined McCombs on Winchester’s high banks. Third generation racer Mike Schuyler campaigned his VW-powered midget at Winchester in the 1980s, while he was attending high school. Now, his first midget looks exactly like it did back in the day, owing to a recent restoration. Schuyler relives his golden years every return trip to Winchester.

“The grandkids suggested that I drive it,” said Wilma Carey of her Curtis midget. Her husband Ron, known in the Indiana racing scene as “Radical Ron,” purchased the relic with plans to race with the Oldtimers but passed away in January 2021. To honor her husband Ron, Wilma, with no prior racing experience, made plans to drive the open-cockpit roadster. Her first run was at another Indiana track in Mt. Lawn. “I wasn’t scared, I wasn’t nervous, it just seemed like the right thing to do go,” said Wilma. In only her second time at the tiller, Carey merged onto Winchester’s 37-degree banking to hot lap with the rest of the group. No doubt, a radical tribute to her late husband.

Tributes, reunions, first-time affairs—sentimental stories wafted from the Oldtimers temporary paddock like sweet campfire smoke. The Whited family have devoted their entire life to Winchester dating all the way back to patriarch Brent serving as the track’s groundskeeper. At the Oldtimers meet, his son Bryan campaigned their 1968 Grant King sprint car for an appearance on the high banks, with grandson Brandon at the wheel. “It’s unspeakable,” said Bryan of the family connection and what it means to see Brandon on track. “Almost tearful just from the joy.”

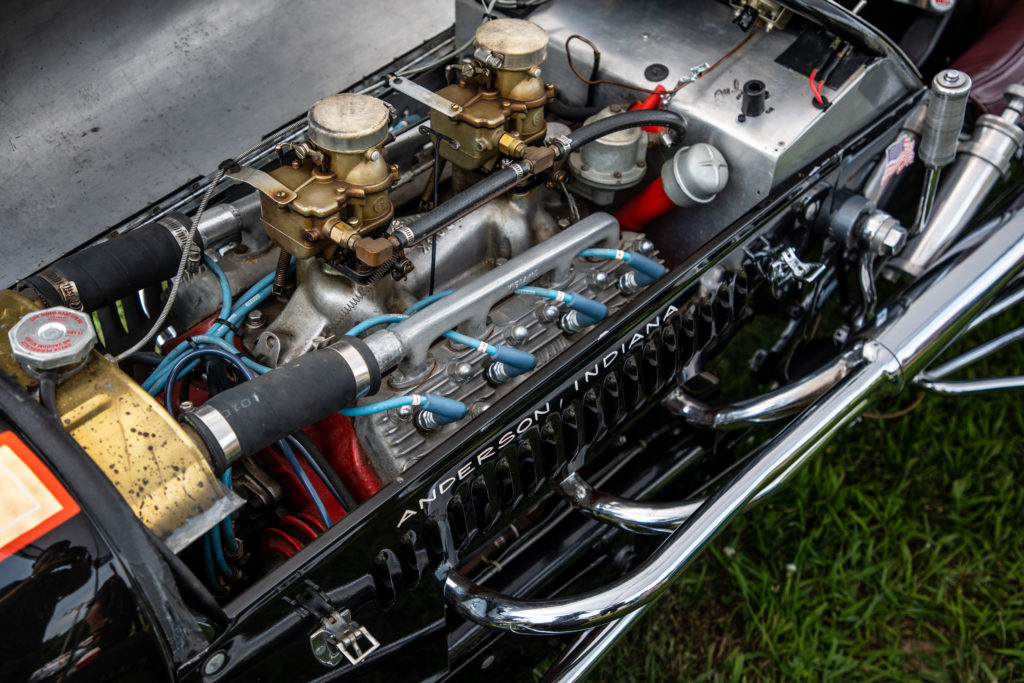

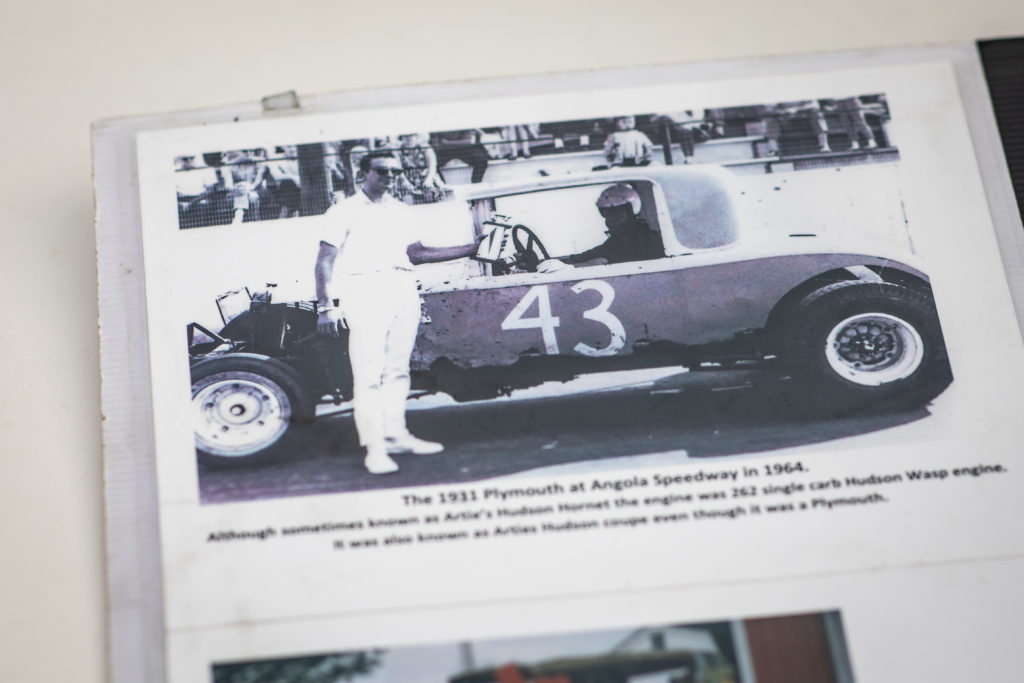

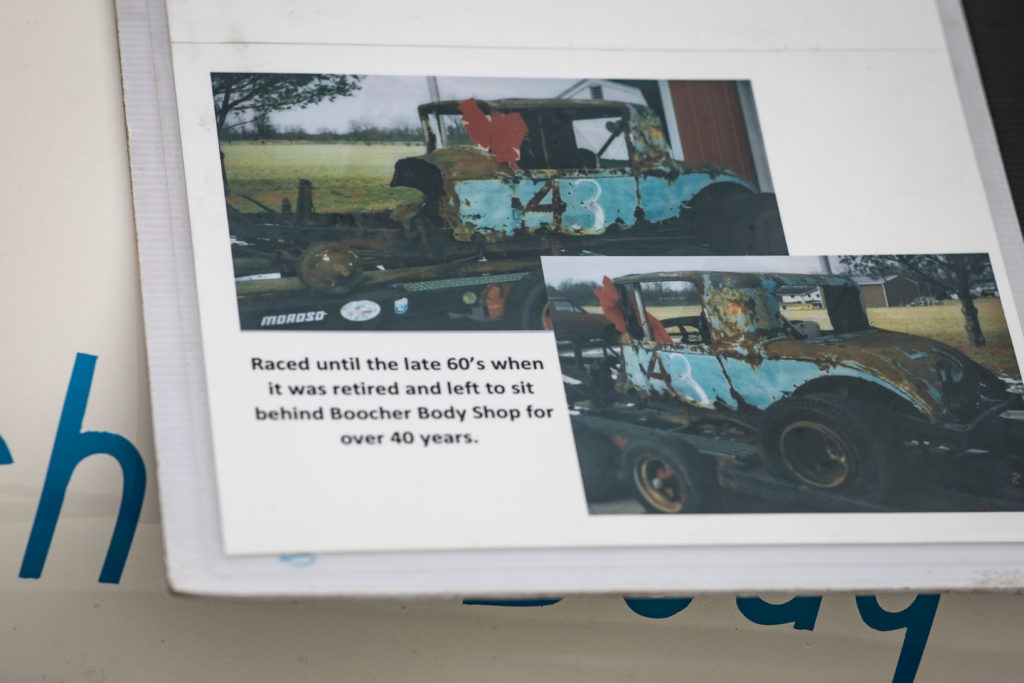

Every participant had either a familial connection to their car or had poured all of their energy into its restoration. The product of a five-year project, Jay Wolf’s 1931 Plymouth coupe looked as if it was Xeroxed from grainy victory lane photos of the car. The Petty Blue 43 stocker was fabricated by Harold Boocher in 1959 and is powered by a 1953 Hudson inline-six. It was a menace to Midwest dirt rings and racked up the wins before it was permanently parked behind Boocher’s body shop some 40 years ago. Wolf’s restoration is immaculate, down to the Ford truck hubs.

To help participants source hard-to-find parts, Wolf, Channell, and other club members started a Facebook group: MORVCC Race Cars for Sale. Group members—and prospective members—can hunt for parts and even whole cars. “A lot of people think this hobby is expensive,” said Channell. “You can get in a really nice car for under $10,000.” Suddenly, I’m wondering why I’m standing in the infield and not riding aboard a vintage circle tracker. Maybe this summer. Maybe next. Either way, Winchester will be there, as it has been, for nearly 110 years.

I’m wondering, is the 98 car pictured Parnelli’s favorite original “Old Calhoun” he won the 1963 Indy in?

Yep, well kind of. It is a replica of that car. I believe IMS Museum has the original car in their care.