The first word of the inscription on Jim Clark’s gravestone is “Farmer.”

The two-time Formula 1 World Champion, British Touring Car Champion, Tasman Series Champion and Indy 500 winner never forgot his roots in the rural Borders region of Scotland. And the Borders will never forget him.

Clark was the greatest driver of his era, killed before his time in a Formula 2 race at Hockenheim in 1968 when he was just 32 years old. At the height of his fame he dated models, was awarded an Order of the British Empire, and even when he moved to Switzerland for tax purposes, he always kept a watchful eye over the family farm near Berwick-upon-Tweed, returning as often as he could to tend his flock.

The gates to his former family home Edington Mains are locked when I pull up outside. David Runciman spots my yellow Lotus and climbs out of his pick-up truck.

“You look like a motoring enthusiast,” he says, and invites me in to take a photograph in front of the house.

Runciman has lived and farmed here for 32 years, his family taking over from those who bought the 1050-acre property from the Clark estate. Fans have always come to Edington Mains to see where Clark first learned to drive, but the numbers have dwindled. “Thirty years ago we’d have one a day turning up, but these days it’s about one a month,” says Runciman.

Clark, Scotland’s first motor racing world champion, moved here when he was just six years old. He grew up driving anything and everything he could on the farm. By ten he was earning sixpence an hour driving a tractor at harvest time, and at every opportunity he’d sneak a go in his father’s 1930 Alvis Speed Twenty, despite barely being able to see over the wheel.

Like any Lotus owner, I feel a connection to Clark, even though he died before I was born. Without Colin Chapman and Clark meeting at Brands Hatch in 1958 would the brand ever have reached the heights that it did? If Clark had survived just a few more years perhaps he’d have even had an Esprit like mine as his company car.

These are the thoughts running through my head as I head out on the narrow B-road towards the village of Chirnside. It was on a road just like this in 1953 that Clark raced past Ian Scott-Watson on the way to a young farmers’ meeting. Scott-Watson was astonished at the speed he was overtaken and the two struck up a friendship based on their shared love of motoring.

Clark’s parents forbade him from circuit racing, although they did permit him to enter local rallies and to help his friend out as a mechanic. In June 1956 Scott-Watson was racing at Crimond in his diminutive DKW Sonderklasse when he offered Clark a drive in practice. Within a few laps he was three seconds a lap faster than the car’s owner.

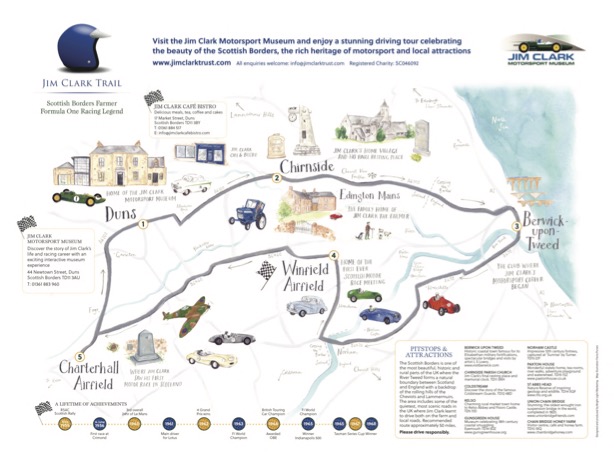

Just over a year later Clark was the designated driver in Scott-Watson’s Porsche 1600S and, at three races at the nearby Charterhall circuit, he finished third, second and then first, bringing him to the attention of local garage owner Jock McBain. It would change everything for the farmer.

Soon racing would take Clark far beyond Chirnside, where the local lad’s exploits are commemorated with a memorial clock—which I do hope is set to run fast.

A further six miles down the road is the town of Duns, home to the Jim Clark Motorsport Museum. On display in the foyer is Clark’s yellow 1967 Elan S3 road car and his double championship-winning Type 25. The museum tells Clark’s story through memorabilia, interactive exhibits, and more than 130 trophies spanning his sensational career.

Here I meet Doug Niven, Clark’s cousin, and his nephew Ian Calder.

“Jim did a couple of races and started doing very well,” Niven tells me. “But his parents still didn’t know about it. The phone started ringing with people saying congratulations, and his parents would say ‘what are you talking about?’”

Garage owner McBain and his Border Reivers team provided Clark with a Jaguar D-Type and soon he was racing abroad for the first time. The Reivers would take him to Spa and Le Mans while at Full Sutton he was the first driver to average over 100 mph in a sports car race.

Back in the Esprit, I head out in search of Charterhall, the scene of Clark’s first victory. The A6105 past Greenlaw Moor is largely straight and I can picture Clark and his Border Reivers flying along here to get to race meetings.

Arriving at what’s left of the former World War II airbase, which was turned into a track in 1952 and once saw not only Clark, but Mike Hawthorn, Roy Salvadori, Jackie Stewart, and Stirling Moss all compete, it’s difficult to imagine a time when crowds three-deep would gather to watch their local hero. Today the site is mostly taken over for grain storage. I gingerly negotiate the gravel perimeter track, spotting a couple of rally cars. Maybe there is still occasional action.

Success here with the Border Reivers would take Clark to Brands Hatch in 1958, where he was narrowly beaten by Colin Chapman, both driving Lotus Elites. Clark’s lap times were quicker than those of the Lotus boss, and he took notice.

Clark was signed to race in Formula Junior in 1960, which he won. He also drove in four Grands Prix for Lotus, taking a podium place in Portugal. The next year he was a fully-fledged Lotus Grand Prix driver. In 1963 Clark won seven out of ten races and became Scotland’s first Formula 1 World Champion. In 1965 he won again and took victory at the Indianapolis 500 as well. Clark would also win three Tasman Series titles, a British Touring Car Championship and even try his hand at rallying.

Getty Images

“Jim was just a natural in a car. Whatever you put him in he’d do well. He’d jump into anything. He just loved driving cars,” says Niven.

Me too, and while I will never come close to Clark’s abilities behind the wheel, I am enjoying the Esprit immensely. There has always been magic in a Lotus chassis, and the way it floats over undulations, yet maintains composure in corners is testament to Chapman’s principles.

The unassisted steering is truly alive and the twin cam engine hungry for revs. The tight pedal box, which makes long journeys challenging, comes into its own as I brake, blip, and downshift. Even the long-throw gearbox seems slicker at speed—although the truth is that the pace isn’t particularly high. Locals in hatchbacks or sedans could easily outrun me, oblivious to their velocity, sealed inside their NVH-proof modern boxes. The Esprit’s proximity to the ground, the rush of wind through the door seals, and the constant feedback through every touchpoint, exaggerates the sense of speed as a I drive towards Winfield, another former airfield turned race track.

Winfield was Scotland’s first racing circuit and the young Clark would often attend as a spectator, before competing in autotests with the Berwick and District Motor Club when he first got his driving licence. Later, at the height of his success, Clark would keep a plane here to make trips to and from home during his hectic racing schedule. “Jim would land his plane at Winfield and then you’d see his Lotus Cortina racing home,” remembers Niven.

“When he’d fly in a few of us would race over to meet him and he’d offer to take one of us up,” adds Calder. “We were all too timid.”

The original runways and taxiways which were used to create the circuit are now crumbling, but it is possible to drive slowly around putting the Esprit where I hope Clark may once have stood or even driven.

The final part of my journey is more melancholy and takes me back to Chirnside to complete my lap of The Jim Clark Trail. On April 7, 1968 Clark was competing in a Formula 2 race at Hockenheim, Germany, when his car inexplicably left the track. The Borders legend died on the scene.

His headstone in the graveyard of Chirnside parish church is dressed with fresh flowers from one of his many admirers who have come to pay their respects. Clark’s achievements are picked out in gold leaf, but that one word in particular stands out: Farmer.

“Jim was still a farmer, and always was a farmer and loved to get back to the farm whenever he could,” says Niven. “When he was back for the British Grand Prix at Silverstone he came to the farm and told the guys that if they could get the hay in before the weekend they could come to the race, and he’d look after them. Jim had just set pole position and when he saw them the first thing he said was ‘did you get the hay in?’ His mind was still on the farm.”