Thirty years ago, in an ivy-covered building in Sussex, England, a world-class team of automotive restorers began a familiar process. Skilled hands lifted the metal skin of a prewar German juggernaut. Pulled the twelve-cylinder heart into its constituent parts. Cleaned them of years of grime and neglect. The men were veterans, unfazed by the scale of the project. But a mark beneath the patina on one massive carburetor stopped them in their tracks.

A Star of David, crudely scratched into the metal of a car campaigned by the Nazi-backed Auto Union team.

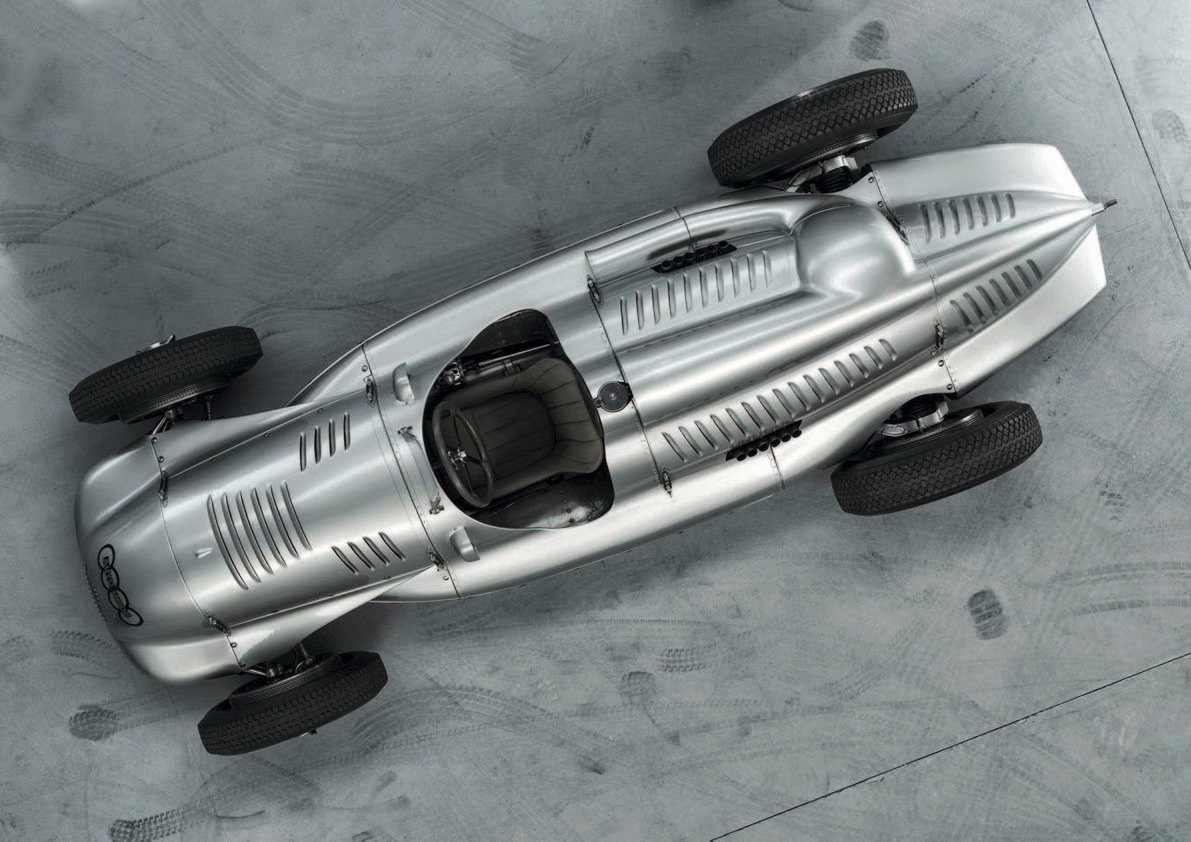

The restoration firm was Crosthwaite & Gardiner. The machine in their shop was a V-12 Auto Union racing machine assumed lost after the Soviets invaded East Germany. One of the mighty Silver Arrows, it had been smuggled to the United States from behind the Iron Curtain by a mix of persistence, bribery, and luck. Two cars—or rather one-and-a-half, when the parts were added up—were so rescued, and the story of their recovery puts a spy novel to shame.

Audi

You can imagine the first shot: Fall of 1939, and a young Paul Karassik is reading a newspaper in his home city of Belgrade, Yugoslavia. The headlines note that heroic Italian racer Tazio Nuvolari has just won the Belgrade Grand Prix in his Auto Union Type D. The circumstances could hardly be more dramatic: During the supporting races, the United Kingdom and France formally declared war on Germany.

The French and Hungarian teams withdrew from the grand prix. Mercedes-Benz driver Manfred von Brauchitisch left for the airport, wishing to fly back to Germany to enlist (though Mercedes team manager Alfred Neubauer eventually persuaded him otherwise). Apart from one local privateer in a Bugatti, only Silver Arrows remained. However, there was a clear rivalry between the Auto Union and the Mercedes-Benz teams. The race went on, though half the field didn’t finish. Von Brauchitisch led but spun, allowing Nuvolari to clinch the win. An Auto Union racer had bested Mercedes, but the world was about to go to war.

Upheaval was not new for the Karassik family. Paul’s father had been an Imperial Russian officer, who had fled to Yugoslavia after the Russian Revolution. Postwar, Paul Karassik emigrated to the U.S., where he met and married his wife Barbara, an immigrant from Germany.

Paralleling the experience of many Europeans after WWII, the fate of the Silver Arrows came down to geographical location. The Mercedes cars survived in what would become West Germany, and Neubauer would again be team manager when Juan Manuel Fangio became world champion in 1954 and 1955. The Auto Union cars lay in Zwickau, to the east. When the Soviet army came, they were taken as trophies, a dozen or so packed into a freight train and sent deep into Russia for study.

Audi

As the world moved into a new age of mechanized warfare, Soviets had good reason to dissect the cars. During the 1930s, the dominance of the German racing teams illustrated a level of technical expertise that characterized a future, successful industrialized nation. The project had begun in 1933, when the governing body of European grand prix racing set a dry weight limit for racing cars of 1650 pounds. The idea was to emphasize lightness over power, reining in speeds and making races a little safer.

When it came to pace, the sanctioning body failed spectacularly. Under Hitler, the German government provided a yearly stipend to go racing—first to Mercedes-Benz and later to Auto Union. The latter began to collect wins in short order thanks to a teardrop-shaped, V-16-powered car designed by Dr. Ferdinand Porsche. By the end of decade, these cars’ supercharged engines were producing over 500 hp. They could spin the rear tires at more than 100 mph.

Decades on, after WWII ground to a halt, Russia had little desire to preserve these vehicles as historic artifacts; they were simply high-tech spoils of war. They hoped to glean technical knowledge from the cars’ design, but the vehicles proved fussy and dangerous in amateur hands. Plus, the Soviets lacked properly refined fuel and the technical expertise to get the cars running smoothly. One Type-D was tested on the road at high speed, but the driver lost control under braking and crashed, killing several spectators. For most of the other cars, dismantling meant destruction, including engine blocks and chassis sawn in half.

Audi

In the West, the whereabouts of the Auto Union cars were mostly conjecture. The curtain had fallen, and as far as anyone knew, the cars had simply vanished, consigned to some scrap heap or melted down.

However, on a trip to Poland in the early 1970s, the Karassiks stumbled upon a member of a car enthusiast club. It seems odd to think that any enthusiasm for cars or racing could exist behind the Iron Curtain, but there were many such organizations. One of them, based in Riga, Latvia, had somehow rescued one of the V-16 Auto Union hillclimb cars from Moscow and preserved it in a local museum.

Rumor held that other Auto Unions were out there. For the Karassicks, the game was on. Because of his fluency in Russian, Paul was able to make connections. Because of a successful career in real estate, he had the resources, too.

Negotiations were largely indirect—much sitting around and quaffing of vodka. A customs agent might casually mention that the tires on his car were getting a bit worn. A new set appeared on his doorstep, and suddenly all the right forms were stamped.

The hunt took decades. On a tip heard in Vilnius, Lithuania, the Karassiks tracked their first car to a small city near Leningrad. The car was little more than an engine, gearbox, and a hacked-up chassis, but it was the discovery they’d been hoping for. They had the pieces trucked out of Russia to Helsinki, Finland, then put on a ship bound for the U.S.

Audi

Since the Auto Union cars had been studied by engineers looking to improve the Soviet car industry, the Karassicks next went to Karkhov, Ukraine, one of the country’s largest engineering centers. During the 1950s, it had produced a series of streamlined-speed record cars. Paul had heard about an old technician who remembered those days and still lived in the area. He might know where some interesting parts could be found.

Parts, not an entire car. This time, however, the Karassicks found plenty to work with: Each part was paid for separately, complete with stamped receipt. Hundreds of bits of metal and paper were loaded into a diesel Mercedes van and again driven out of the country to Helsinki, and then to the United States. In a fitting turn of events, the Karassiks ended up storing all their finds in a warehouse in St. Petersberg Beach, Florida.

Finding a restoration shop worthy of bringing the Auto Unions back to life was relatively simple, given the short list of firms capable of doing so. Crosthwaite & Gardiner had the most experience, having restored three Auto Unions. In 1990, work began.

- Audi

The first car was built to 1938 single-stage supercharged specification, with work completed in 1993. C&W then restored the second car to a later, 1939 two-stage supercharged specification. Both cars appeared in public in 1994, at the Eifel Classic, held at the Nürburgring.

Since then, Audi has acquired both of the Karassik Auto Unions. It continues to preserve and maintain both, along with a third Type-C Auto Union discovered in a museum in Munich after WWII.

No one knows who scratched that Star of David into the carburetor. The mark could been made before the war or after its Soviet capture, since, when the engine is assembled, the star is hidden. In either case, it is a sobering reminder that cars and motorsports don’t exist in a vacuum. They are intimately connected with human stories, without which vehicles never become more than rubber and steel. Those stories are why we save cars.

- Audi

like this.