On October 15, 1964, seconds after pushing the land-speed record past 500 miles per hour on the Bonneville Salt Flats, Craig Breedlove punched the button to release the parachutes attached to his jet-powered Spirit of America. They all failed. He careened off course, sliced through a pair of telephone poles, catapulted over a berm and nosed-dived into a brine lake.

Fortunately, he’d had the presence of mind to unlatch the canopy while he was in the air. As water flooded into the cockpit, he popped his harness and swam to safety. Soaked but unhurt, he was lounging on a piece of debris when the emergency crew arrived. “And now for my next act,” he told them, “I’m going to set myself on fire.”

Breedlove and crew observe the partially-submerged jet racer. The crash came minutes after he set a world land-speed record of 526.26 miles per hour.

Breedlove, who died Tuesday at the age of 86, was the first man to exceed 400, 500, and 600 miles per hour on land. Immortalized by the Beach Boys as “a daring young man [who] played a dangerous game,” Breedlove was the winner of a thrilling, high-profile, three-way land-speed battle with the Arfons brothers in the fall of 1965. After a frantic six-week stretch of steely-eyed one-upmanship, Breedlove ended up holding the record at 600.601 mph.

Born in 1937, Breedlove was a prototypical SoCal hot-rodder who pushed a supercharged ’34 Ford coupe to 154 mph on the dry lake at El Mirage before graduating to an Oldsmobile-powered belly tank that went 236 mph at Bonneville. After a stint at Douglas Aircraft, he worked as a firefighter in Costa Mesa when he was bitten by the jet-engine bug.

Although jet-powered dragsters had been on the exhibition circuit for several years, Los Angeles physician Nathan Ostich was the first man to take a jet car to Bonneville; his Flying Caduceus topped out at 331 mph in 1962. Later that same year, jet dragster driver Glen Leasher was killed when his land-speed car, Infinity, snap-rolled at close to 400 mph.

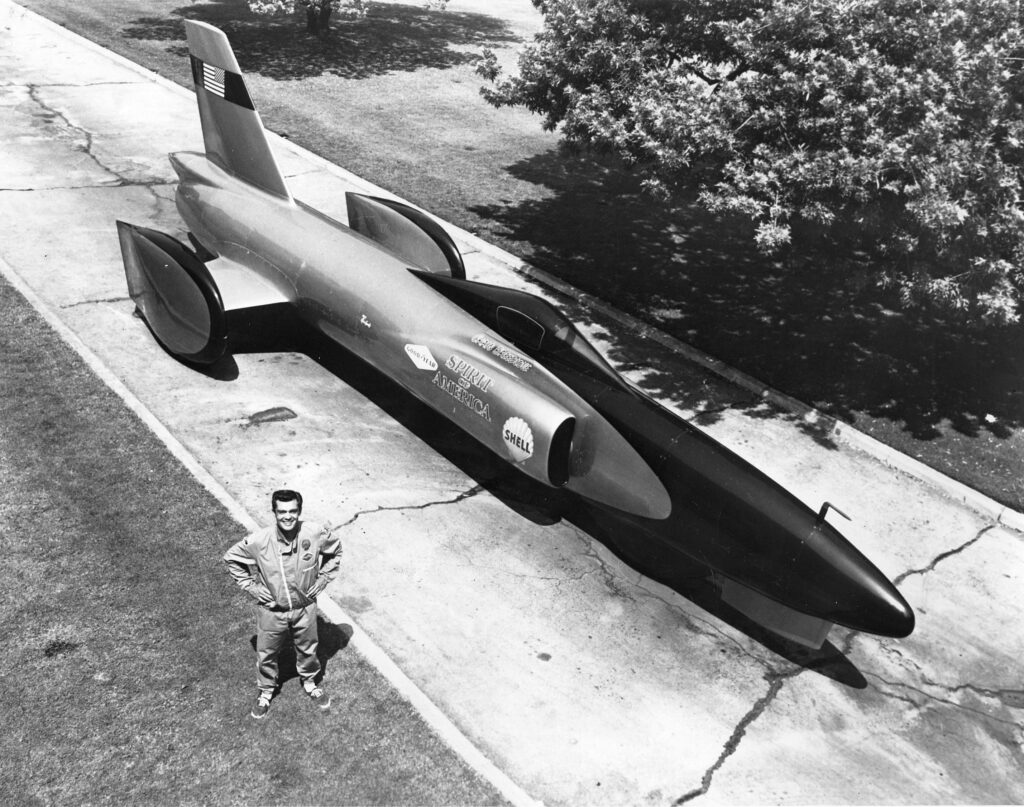

Breedlove pulls the newly-built “Spirit of America” out of his garage. (Photo via Bettman/Getty)

Breedlove and crew look over the 39-inch diameter aluminum wheel designed for Spirit of America. (Photo by Eric Rickman/The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images)

Meanwhile, Breedlove spent $500 to buy a General Electric J47 turbojet salvaged from a Korean War-era F-86 Sabre. Working out of a garage near LAX Airport, he fashioned a low-slung, three-wheeled streamliner that he dubbed Spirit of America. The name was pure marketing gold–a sign of his promotional genius. Handsome and personable, Breedlove lined up sponsorship from Shell and Goodyear. In 1963, while wearing sneakers and a crash helmet festooned with painted stars, he claimed Fastest Man on Earth honors with a speed of 407.447 mph.

Breedlove next to his first Spirit of America jet car. (Photo by ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images)

Breedlove returned the next year to set two more records. In 1965, he faced fierce competition from Art and Walt Arfons–two middle-aged Midwestern brothers who worked out of adjacent junk-strewn lots in Akron, Ohio, separated by fences and decades of estrangement. To outrun them, Breedlove built a four-wheel car, Spirit of America–Sonic 1, around a more powerful GE J79 taken from an F-104 Starfighter. It was in this car that Breedlove claimed his last two land-speed marks.

Breedlove and Spirit of America-Sonic I (Photo via Bettman/Getty)

Breedlove and crew under Spirit of America—Sonic I. (Photo by Bud Lang/The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images)

As a cherry on top of this sundae, he also co-drove to endurance records on a large oval marked out on the salt in a Cobra Daytona Coupe in 1965 and then an American Motors AMX on a Goodyear test track in Texas in 1968. Breedlove was 31 years old, and he would never scale such rarified heights again.

Breedlove’s land-speed record was shattered in 1970 by Gary Gabelich and the rocket-powered Blue Flame. Thirteen years later, Briton Richard Noble raised the record to 633.47 mph in Thrust2. But one great prize remained: breaking the sound barrier.

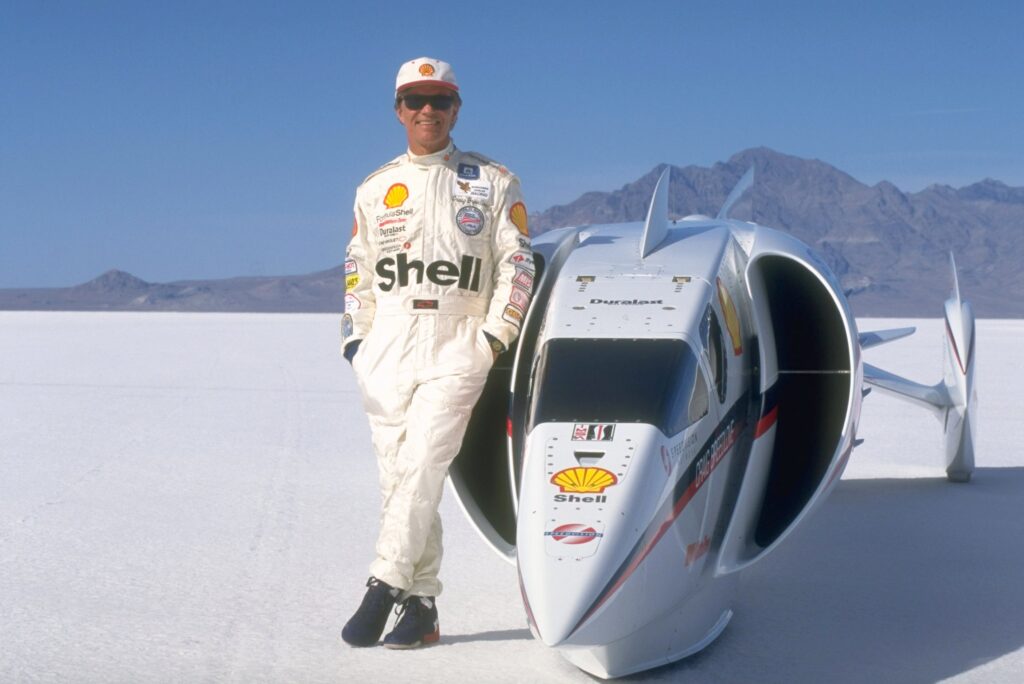

After spending three decades making money in real estate, Breedlove designed a third Spirit of America around another J79, this one out of an F-4 Phantom. With a small team and sponsorship from Shell, he put the car together in a shop he’d fashioned out of an old Ford tractor dealership in the small Northern California town of Rio Vista. “We built everything from scratch, just the way I did the first time in my dad’s garage in El Segundo,” he said.

By 1996, Bonneville was no longer big or smooth enough for land-speed attempts. Instead, Breedlove headed to the concrete-hard playa of Black Rock Desert, now better known as the home of the annual Burning Man bacchanal. Just before starting a run, he misheard a radio communication about the speed of the crosswind blowing across the course–not 1.5 mph but a potentially catastrophic 15 mph.

Breedlove his third Spirit of America, circa 1996 (Photo by Robert Beck)

Unaware of the danger and eager to get the run in before the weather deteriorated, Breedlove took off and lit the afterburner. While he was thundering along at 675 mph, a gust buffeted his car and sent it up on two wheels. Bicycling wildly, he executed the world’s fastest U-turn and screamed through the spectator area. Although he miraculously avoided hitting anything–or anyone–the car was damaged too badly to continue.

Breedlove’s Spirit of America is towed out to Black Rock lake bed for an land-speed attempt.

Breedlove returned the Black Rock Desert the next year to go mano-a-mano against a well-funded British team lead by Richard Noble, who’d hired RAF pilot Andy Green to drive a twin-engine behemoth called ThrustSSC. Breedlove was hamstrung by engine trouble and a lack of money, and he could only watch the shock wave produced when Green broke the sound barrier.

Black Rock, Breedlove, 1997. ( Photo by Paul Harris/Getty Images )

Breedlove spent much of the next decade plotting another assault on the record, but he was never able to put the necessary financing together. Finally, in 2006, he sold his car to adventurer Steve Fossett, who underwrote a substantial redesign. The project died when Fossett was killed in a plane crash the next year while scouting sites for potential record runs.

Were it not for a garbled radio transmission, Breedlove might well have been the first man to officially go Mach 1 on land. Even so, with five land-speed records to his name, he still occupies prime real estate in the pantheon of land-speed-record deities and deserves to be remembered as one of America’s motorsports heroes.

“The thing I admired most about him is that he was so dedicated to breaking the record. It was his entire life,” says BRE founder Peter Brock, who spent six weeks on the playa with Breedlove in 1997. “He built three land-speed record cars in his garage and spent every dime he had on them. We’ll never in our lifetime see a guy like him again.”

(Photo by National Motor Museum/Heritage Images/Getty Images)

A long time friend of my also gone parents,I only met him as a young child.

I didn’t know him except for my parents story’s about their time together through out the 60’s.

Mom talked with him on the phone for years.

RIP to an American Racing Hero.

In 1967 I had an engine for my Triumph TR3 built by a mechanic named Doc Bunce who worked with Breedlove on one of his land speed record cars.

I have two personal memories of Craig Breedlove. First, I saw him drive his AA/FD called “Spirit II” at Riverside in the mid 1960s. It was new out of the box, and unfortunately wasn’t very fast, but sure looked good.

Second, in the 1980s or 90s, I was in a parking lot of a fast food joint in Anaheim, IIRC, and there was a semi and trailer with markings that indicated that he and his son (J. Craig Breedlove?) were working on another jet car.

I’m sad to hear of his passing, but he’s a big piece of Land Speed Record history, and will live forever in the record books. RIP, Craig, and thanks for an exciting era in motorsports. You’re one of my idols.