I recently spoke to a gentleman who happened to see Dan Gurney win the French Grand Prix in 1964. Coincidentally, another spectator at Rouen that afternoon in June was film director John Frankenheimer. In fact, the drama and spectacle of the race inspired him to make a movie about Formula 1, released two years later as Grand Prix.

I watched Grand Prix a few nights ago. I came away from the long slog—the movie runs 179 minutes—with two major takeaways: First, the screenwriter is at the bottom of the totem pole in Hollywood. And second, it’s impossible to make a movie about racing that satisfies both hard-core fans and fair-weather filmgoers.

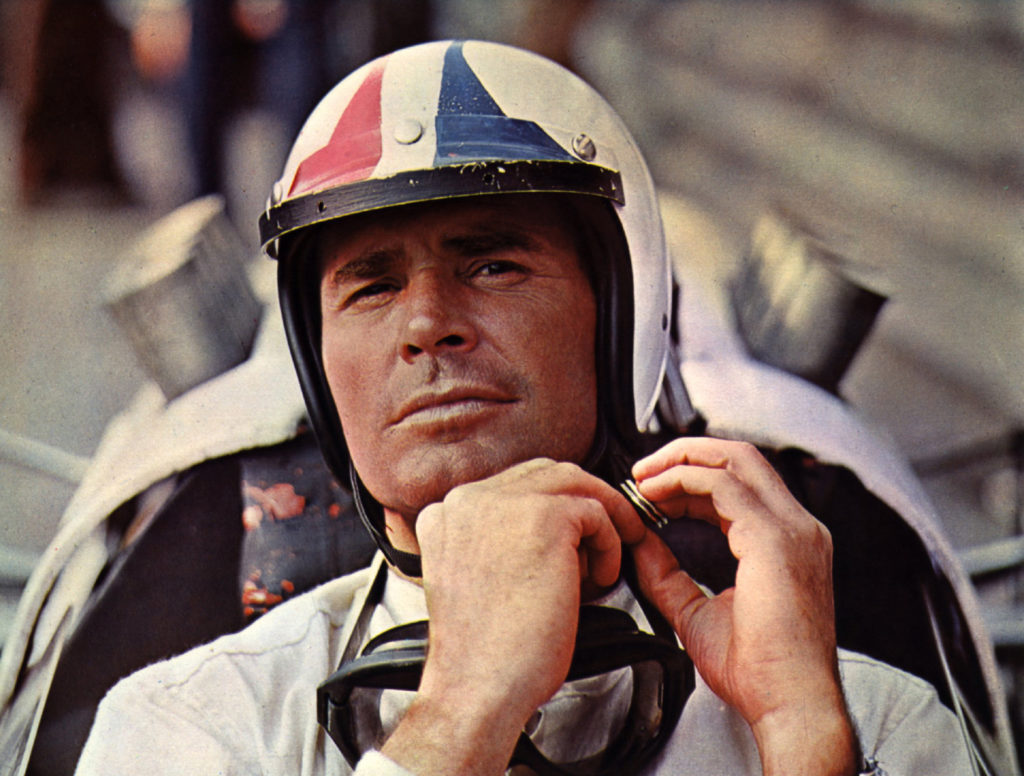

(Photo by Movie Poster Image Art/Getty Images)

Now, wait, I know what some of you are saying: Grand Prix is the greatest racing movie ever made! And I totally agree, but that’s only because the competition sucks—yes, that includes Steve McQueen’s shambolic epic, Le Mans. Grand Prix is worth watching for the bravura opening sequence at Monaco and the riveting footage in the rain at Spa-Francorchamps. Overall, the movie is sabotaged by clunky melodrama, cringeworthy romances, and just about every racing cliché known to man.

I used to blame these flaws on screenwriter Robert Alan Aurthur. After visiting the Margaret Herrick Library at the Fairbanks Center for Motion Picture Study in Beverly Hills and reading more than half-a-dozen versions of the script, some bearing handwritten notes and others literally cut and pasted, I’m convinced that his initial vision was far more compelling and authentic than the Hollywood-ized movie that ultimately made it to the silver screen.

James Garner ejects himself from his burning race car for a scene in Grand Prix. (Photo by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/Getty Images)

Aurthur wrote eloquently about race relations for movies and TV and earned an Oscar nomination for All That Jazz. I’d always assumed that he didn’t know anything about racing, so I was surprised to discover that his original script used the proper French names for the corners at Monaco and name-checks pre-war heroes such as Nuvolari and Caracciola. He even got the jargon right, describing cars that drift and clutches that bite. I was also impressed that the concept for the spectacular title sequence, which interposed close-ups of wrenches and exhausts pipes with shots of the crowd and drivers girding for battle, was on the page from the start.

(Photo by FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images)

Filmmaking is a dynamic proposition, though, and things inevitably evolve during a shoot. Dialogue, plot points, even the cast change. Grand Prix was especially challenging because Frankenheimer was using actual Formula 1 races as set locations and for stock footage. Even though the Belgian Grand Prix wasn’t in the original script, it ended up filling a major section of the movie because the action in the rain was so breathtaking.

(Fun footnote: Jackie Stewart, badly injured when he crashed through a telephone pole, thought the helicopter hovering over his wrecked BRM was about to whisk him off to the hospital. In fact, it was filming the race, and he had to endure a long, painfully bumpy ride in a dingy ambulance to a medical center with cigarette butts littering the floor. This was one of the incidents that motivated Stewart to start agitating for more safety measures in racing.)

(Photo by FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images)

Aurthur’s script was initially more concerned with the nuts and bolts of racing—who finished where, and how. Passing was accomplished realistically rather than following the Days of Thunder/Ford v Ferrari paradigm of simply shifting into a higher gear. Speaking of Ford v Ferrari, Authur also envisioned races at Le Mans and the Targa Florio, with American Pete Aron (played by James Garner) competing in a Ford against Ferrari sports prototypes. After redlining his engine and blowing it up, Aron snarls, “I’d rather be dead than finish second!”

Aron, who’s largely a cipher and a bit of a jerk in the movie, originally benefited from a deeper backstory (son of a commercial fisherman who jumped ship when he was 17 to seek fame and fortune) and a more complex bromance with Izo Yamura, the Soichiro Honda stand-in portrayed by Toshiro Mifune. Alas, most of this material ended up on the cutting-room floor, probably because Mifune didn’t speak English, and his lines had to be dubbed.

James Garner (center) and Toshiro Mifune (front) (Photo by Camerique/Getty Images)

The movie is lamentably full of preposterous tropes about drivers who are haunted by feelings of inadequacy, sexual and otherwise, and an eat-drink-and-be-merry-for-tomorrow-we-die ambiance hangs over the whole story. A lot of this material mars the original screenplay, but Aurthur managed to shift the focus from racing in isolation to a broader commentary on the human condition.

“All the drivers I’ve ever known have been fools and madmen—until you, that is,” the movie’s Enzo Ferrari doppelganger tells world-weary Corsican champion Jean-Pierre Dalvaux (later changed to Sarti) in a deleted conversation. “Not because they live with danger and die in agony, but because they are in constant, fruitless pursuit of the impossible, which is to be a winner. We are all losers, Delvaux, because we are fallible; we are human.”

(Photo by Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images)

The biggest problem with the film isn’t what was cut; it was what was added. The centerpiece of Grand Prix becomes the doomed and hackneyed romance between Sarti and the clueless American fashion journalist Louise Frederickson. Sarti, played by Yves Montand, utters what I consider one of the worst lines in film history: “Do you ever get tired, Pete?” Really, it’s poor Eva Marie Saint, as Louise, who gets stuck with clunker after clunker.

In my opinion, at least, Grand Prix hits rock-bottom with a late addition to the script. After the mortally wounded Sarti is loaded into an ambulance, the traumatized Louise holds up her palms—slathered with the blood of her dying lover—and shrieks at the gawkers, “What do you want? Is this what you want? Is this what you want? Is this what you want?” Jeez, Louise. In the original screenplay, Aurthur had made do with a relatively restrained, “Stop it!!! Stop it!!!”

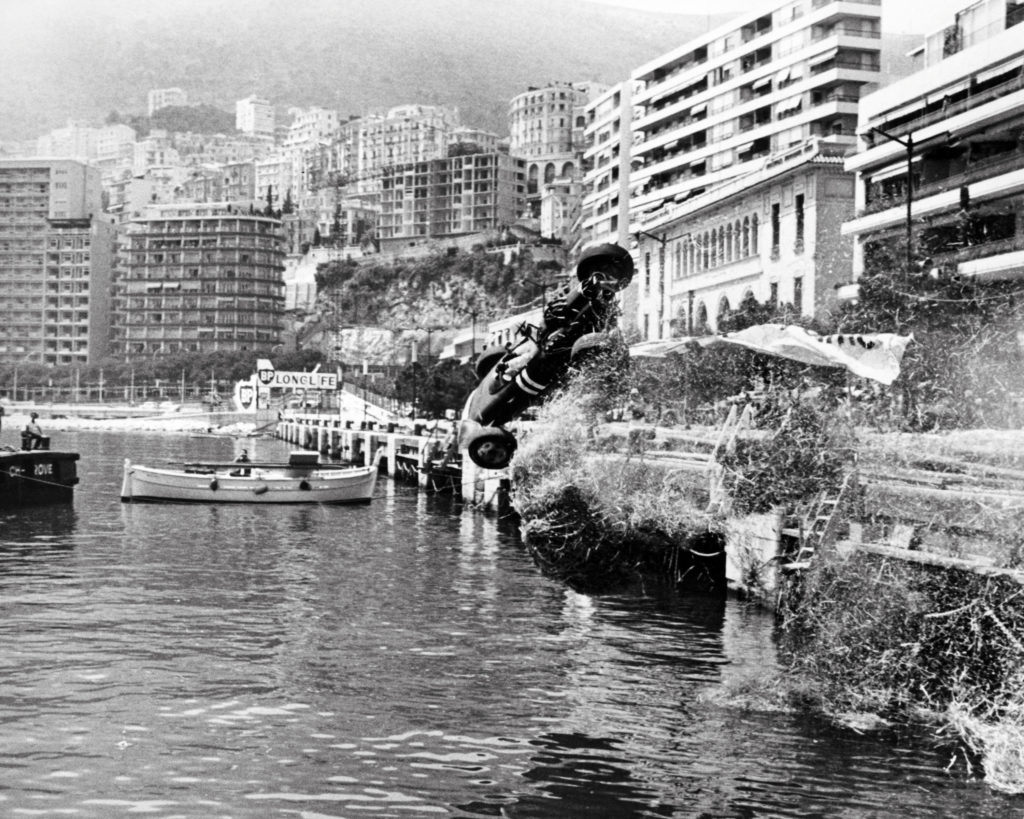

Yves Montand is rescued from his wrecked car. (Photo by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/Getty Images)

The movie closes on a thoughtful but generally upbeat note after Aron clinches the World Championship at Monza. Aurthur had intended to end with something much more ambiguous. A couple of somber and ruminative funeral and post-funeral scenes were cut. Also axed was a thoughtful post-race conversation between Aron and Yamura. Curiously ambivalent despite winning the title, Aron struggles to articulate the futility of trying to top this achievement.

“When does it end?” he asks.

“It doesn’t,” Yamura says—an unusually nihilistic sentiment for a sports movie.

Ultimately, Frankenheimer, producer Edward Lewis, and MGM opted for a more palatable product, and their vision was the seventh-highest-grossing film of 1966. After reading Aurthur’s original script, I can’t help but wonder—as with Senna racing for Williams or Valentino Rossi testing for Ferrari—about what might have been.

- James Garner complaining to Toshiro Mifune in a scene from the film ‘Grand Prix’, 1966. (Photo by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/Getty Images)

- Francoise Hardy at the wheel of a Formula I Ferrari in the film ‘Grand Prix’ by John Frankenheimer. (Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

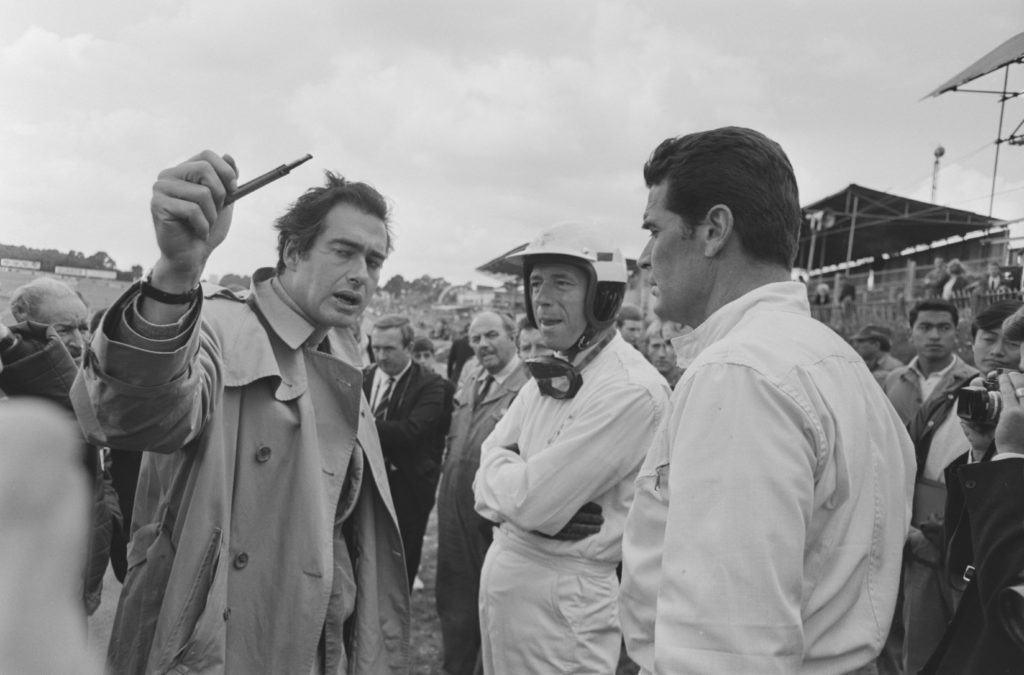

- From left to right, director John Frankenheimer (1930 – 2002) and actors Yves Montand (1921 – 1991) and James Garner (1928 – 2014) filming the Formula One racing movie ‘Grand Prix’ at Brands Hatch, England, 18th July 1966. (Photo by Victor Blackman/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

- Jessica Walter with actor James Garner in a Maclaren sports car which has been painted white to represent a Japanese car in the film GRAND PRIX. the child is 8yr. old Gigi Garner Daughter of James Garner July 1966 ©Mirrorpix.com (Photo by Eric Piper/Mirrorpix/Mirrorpix via Getty Images)

- James Garner races in a scene from the film ‘Grand Prix’, 1966. (Photo by Metro Goldwyn Mayer/Getty Images)

- Kino. Grand Prix, 1960er, 1960s, Film, Formel 1, Grand Prix, Rennfahrer, Rennwagen, racing car, racing driver, Grand Prix, 1960er, 1960s, Film, Formel 1, Grand Prix, Rennfahrer, Rennwagen, racing car, racing driver, Eva Marie Saint, James Garner Rennfahrer Pete Aron (James Garner) hat gute Aussichten auf den Weltmeistertitel in der Formel-I Klasse. Damit ist er eine Zeit lang auch Favorit von Louis Frederickson (Eva Marie Saint)., 1966. (Photo by FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images)

- Brian Bedford BRM car climbs a cliffside wall after his collision in a scene from the film ‘Grand Prix’, 1966. (Photo by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/Getty Images)

- James Garner stands holding a trophy cup and a bottle of champagne as Toshiro Mifune looks at him in a scene from the film ‘Grand Prix’, 1966. (Photo by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/Getty Images)

Even with all it’s flaws, and there are many, Grand Prix is still the best film to date about Formula 1.

Unsurprising really when you consider it was made in the golden era of the sport. The fatality rate was horrific but the technological advance in F1 cars of the sixties and the skill needed to pilot them successfully was as near to a perfect combination as there has ever been.

In 2013 two couples went to see Rush, directed by Ron Howard. I was a F1 fan, my friend was a casual fan. My wife had been to Watkins Glen twice and knew F1 existed, and my friends wife thought she might have heard of F1. Each one of us had a different perspective, but we all enjoyed the film for very different reasons.

A great film? No, but one I watch at least annually.

The romances were pretty silly, and yes, the screaming Eva Marie Saint was a serious negative for someone who loves racing and hates injuries, but it’s still a movie I love watching.

In Sarti’s wreck, at least in the movie, he was thrown from the car, so the picture of rescue workers taking him from the car must have been one of those alternate scenes.

I am surprised that this article does not mention the fact that the Fformula 1′ cars used in Grand Prix

were actually Formula TWO cars…….

Loved seeing some of the actual F1 stars in a few of the scenes. Dan Gurney among them. But what I found annoying was the constant repetition of the theme music. Over and over.

Shortly after my arrival in Europe I bought a Ferrari 275 GTB and went to Modena with it. While parking it in the underground garage at the Real Fini hotel in Modena in 1967 I noticed a piece of cardboard laying in my parking spot. It was a makeshift scene card for one of Frankenheimer’s scenes in “Grand Prix”. What a souvenir. I still have it