A few racers with professional or academic backgrounds in engineering have had great success on the track, in part because of their ability to communicate the car’s behavior to the team. However, even Mark Donohue and Niki Lauda didn’t do much engineering on their own cars.

British engineer Michael Parkes raced successfully at the highest levels of motorsport and headed the development of the Hillman Imp, a technologically superior contemporary of the Mini Cooper. (The car’s design was brilliant; dealer support, production quality, and marketing were not.) Parkes was recruited by Enzo himself to develop race cars for Ferrari at a time when the Scuderia was dominant. Later in life, Parkes would develop the Lancia Stratos into a winner of multiple world rally championships.

You probably don’t even know his name.

Born in 1931, Michael Parkes followed his father—managing director and later chairman of Alvis—into the automotive industry, starting his career at the Rootes Group in 1949 as an 18-year-old apprentice engineer at Humber, a motorcycle and automobile company. (Along with the rest of the Group, which some considered U.K.’s General Motors, Humber was eventually purchased by Chrysler Corporation in 1967.) Three years after he arrived at Humber, Parkes’ father gave him a MG TD on the occasion of his 21st birthday, with the condition that he not race it. Parkes immediately did—and won.

He soon started club racing, eventually moving from MGs to Lotuses. He did well enough for none other than company founder Colin Chapman to offer him a stint as a reserve driver for the Lotus works team at the 1957 24 Hours of Le Mans. This was when Parkes was already working full time at Rootes, as the project engineer on the Hillman Imp.

According to his associate and racing buddy Tim Fry, the two young men—Parkes was 24, Fry was just 20—approached the Rootes technical director about the small car project that would become the Imp.

“We were very bored with the sort of cars Rootes were producing and with the arrogance of youth we went to the technical director and told him we could design just the car he needed. He just said, ‘All right, get on with it!’”

In 1964, the French racing publication L’Equipe rated Parkes as #13 on its list of the top 25 drivers in the world. Photo: Ferrari

Parkes continued to race on the side. His success behind the wheel earned more and more attention, and heavyweights like Graham Hill started to offer him rides.

While Parkes was at Le Mans in 1961 to supervise Rootes’ Sunbeam Alpines competing in the race, the Ferrari team gave him the opportunity to take one of the factory 250GTs out on the La Sarthe circuit during testing. Parkes proved faster than Enzo’s own drivers. Small wonder that at the end of 1962, Parkes left Rootes to work for Ferrari as a reserve driver and development engineer.

He competed in Formula 1 for Ferrari, but his real métier was racing sports cars for Il Commendatore. Parkes won at Sebring and Spa in 1964, Monza in 1965, and Monza and Spa in 1966. The good times wouldn’t last, however.

Michael Parkes leading Graham Hill, both in Ferraris at the 1965 Nürburgring 1000Km. Photo: Wiki Commons

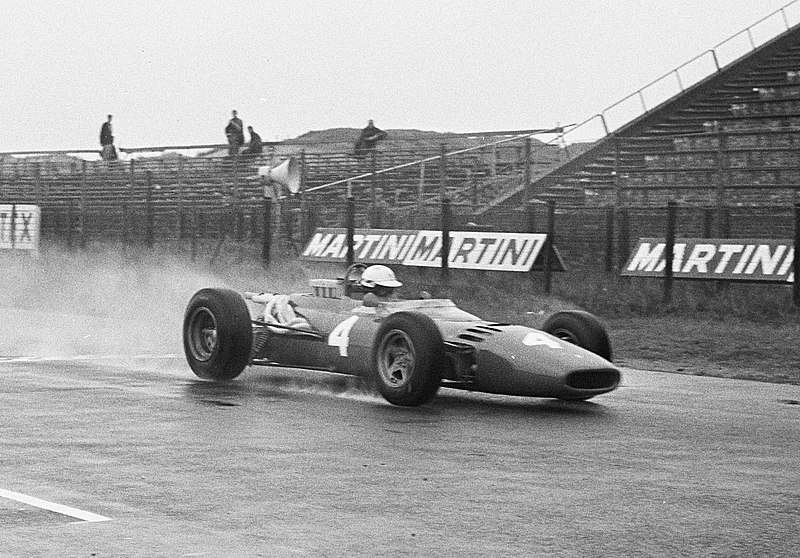

Parkes in a Ferrari at the Dutch Grand Prix, 1966. Photo: Dutch National Archives

The following year, while racing at Spa, Parkes’ tires became slick with oil. His Ferrari spun, then rolled.

Race cars of the era had few, if any, safety features. They had spindly tube frames and drivers were often flanked by fuel tanks. Many drivers opted to not wear seat belts as they preferred the possibility of being thrown from the car and crippled to that of being trapped in the car and getting burned to death.

As his Ferrari rolled, Parkes was ejected from the cockpit and dragged behind the car as it came to a stop. He ended up in a coma for a week and his leg injuries were so severe that his doctors considered amputating both limbs.

It took six months of recuperation and rehabilitation before Parkes could drive again. When he did return to full-time work at Ferrari in 1969, Enzo made him a financial offer described as “staggering”: Management of the Ferrari sports-car racing program in addition to his current role as engineer.

The catch was that Enzo considered Parkes to be more valuable as an engineer than a driver. If he accepted the offer, Parkes wouldn’t race.

Parkes in 1969 at the Nürburgring. Photo: Wiki Commons

Parkes was a born racer. In 1971, he left Ferrari, competing as a privateer in a Ferrari and later in a Pantera for the Filipinetti team.

Whether because of age or 1967’s accident, Parkes was not able to recover his form or pace. After the Filipinetti team broke up in 1973, Parkes moved to Lancia as the development engineer for the new Stratos rally car, powered by a Ferrari-designed engine. Under his direction, the Stratos won the 1974 Targa Florio and the World Rally Championship three years running, from 1974 to 1976, making it one of the truly iconic cars of its period.

Michael Parkes died in a road accident in 1977 when he rear-ended a 43-ton truck in his Lancia. He was killed instantly.

Lancia

The exceptional range of Parkes’ portfolio distinguishes him from other successful engineer-drivers, a roster that includes three-time Indy 500 winner Mauri Rose and Chaparral creator Jim Hall.

Rose worked for GM’s Allison transmission division in Indianapolis and also had a role in the development of the V-8-powered Corvette and a number of high-profile GM show cars, including the turbine-powered Firebirds. One year he qualified for the Indianapolis race during his lunch break from the transmission plant, which sat across the street from the Motor Speedway.

Regarding Jim Hall, Roger Penske, who himself won four consecutive SCCA national championships as a driver, said: “Jim was one of the great road-racing drivers of his time. It was Jim who made me realize that you can’t win races without good equipment.” Hall, who trained as an engineer at CalTech, won with equipment of his own making and his innovations in those race cars continue to resonate today.

No disrespect to Rose and Hall, but Rose never was in charge of engineering an entire vehicle, and Hall’s engineering talents were generally restricted to racing vehicles. Parkes’ applied his engineering skills to both an innovative economy car and some very successful racing machinery, and during much of that time he also competed at the highest levels of racing with success.

To give you an idea of the high regard Parkes was held in by the racing community, TransAm champion David Hobbs, no slouch behind the wheel himself, told me that the best race he ever had was on the way to compete in an actual race at Goodwood in the U.K. in 1959.

Driving on narrow B roads through small towns and villages to the race course, Hobbs found himself being overtaken by someone driving a Hillman Minx at pace. Hobbs took up the challenge, and the two cars went wheel to wheel, exchanging leads all the way to Goodwood. Hobbs didn’t say who got to Goodwood first but he did say that when he arrived at the track, he discovered that his unknown competitor was Michael Parkes.

Michael Parkes was a man of singular distinction in automotive history, combining excellence in engineering and racing as few, if any, others have done. You should remember his name.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.