Imagine Lewis Hamilton instructing rival Red Bull to build a car for the Indianapolis 500, and then introducing the team to a new engine supplier. While this may be unthinkable today, just over 60 years ago, this exact scenario played out with Dan Gurney and Lotus.

American racer Dan Gurney had never driven in the United States’ richest—and most famous—race, the Indianapolis 500. In 1962, he decided to join the Indy crowd.

In his Brickyard debut, Gurney drove for fellow American dynamo Mickey Thompson in the Harvey Aluminum Special. The bloated, rear-engine roadster ran a production-based Buick V-8, unlike most of its Offenhauser competitors. It was underpowered but Gurney still qualified an impressive eighth.

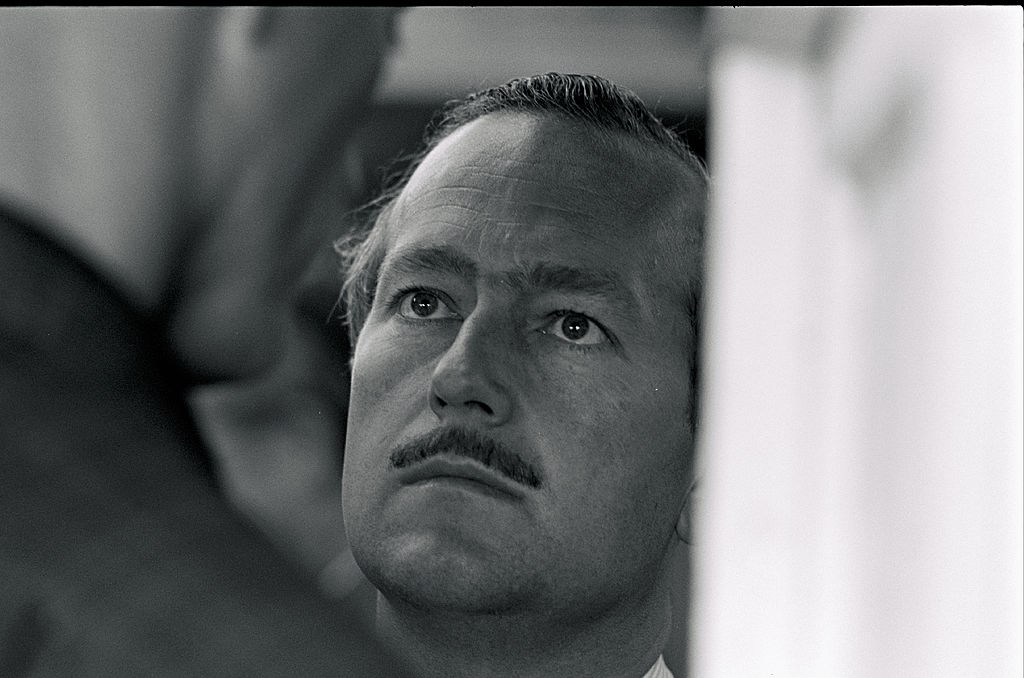

Mickey Thompson (left) and Dan Gurney. (Photo by Ray Brock/The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images)

Days later, Lotus boss Colin Chapman unveiled his Lotus 25 at the 1962 Dutch Grand Prix. Gurney, having made the flight across the Atlantic, was driving for Porsche. Chapman’s revolutionary, slim design caught the eye of many people in the paddock, Gurney included.

The Lotus 25, which Chapman had initially sketched out on a napkin, was the first-ever Formula 1 car to use a monocoque chassis. Since the car was constructed from a box, which looks like a metal canoe, it was more rigid and nearly three times lighter than Chapman’s previous F1 design. After he witnessed the car compete, Gurney reportedly told Chapman: “My god, if someone took a car like this to Indianapolis, they could win [the race] with it.”

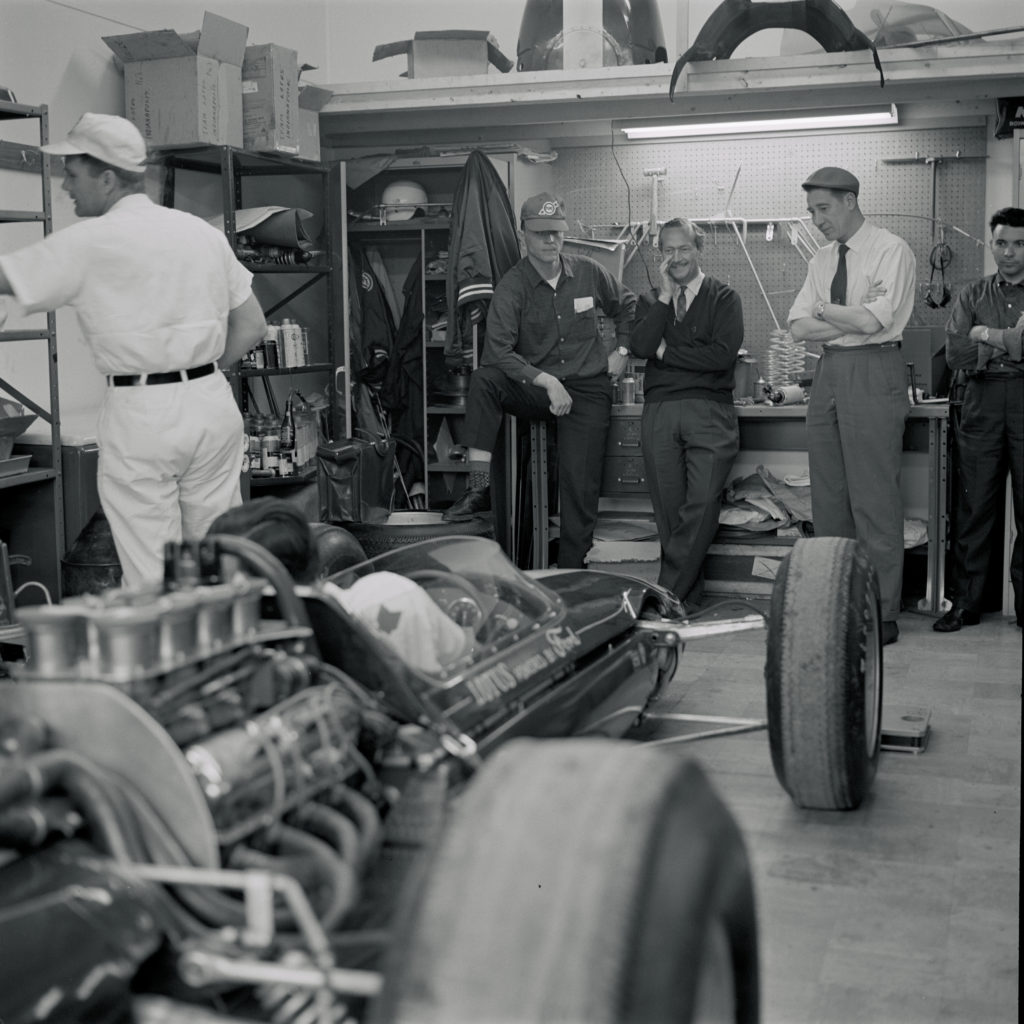

Lotus founder Colin Chapman. (Photo by Bob D’Olivo/The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images)

After the Dutch race, Gurney contacted the Lotus boss and asked if he’d like to attend the 500 as a spectator. The American even payed for Chapman’s airfare. (Fun fact: Apparently Chapman was so hesitant to go that he postponed making a decision until the ticket actually arrived.) Gurney retired from the 1962 race with engine trouble.

The blown motor didn’t matter. Gurney had succeeded in stoking the English engineer’s interest. Chapman’s biographer Gerard Crombac recalled: “I well remember after his return, when he described the old-fashioned, front-engined ‘roadsters’ he had seen, he was laughing his head off.” In Chapman’s eyes, Indy was in the technical dark ages compared to F1. The field, which was composed primarily of primitive, front-engine roadsters, was ripe for the taking.

A pack of Indy dinosaurs. (Photo by ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images)

Chapman was also notorious for following the dollar. During his stateside field trip, he noticed the substantial purse awarded to Indy 500 competitors. The 1962 winner earned $125,000 (adjusting for inflation, that’s about $1.16 million in today’s dollars). The cash was more than Team Lotus would earn in an entire grand prix season.

If Chapman ever wanted to win Indy’s big money, he would someone to sponsor the Lotus effort.

As luck would have it, Ford executives Don Frey and Dave Evans were at Indy in ’62. The duo reasoned that competing in, and ideally winning at, the legendary 500 could be a game-changer for the Blue Oval. Ford’s C-suite knew all about Gurney, too. They were impressed by his showing in their Galaxie stockers at the Daytona 500.

The stars were aligning for Gurney and new convert Chapman.

After the British Grand Prix, which was won by Jim Clark in a Lotus, Chapman and Gurney flew to Ford headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan. The Englishman came across as arrogant and dismissive of the peculiarities and traditions of Indy.

The famously diplomatic Gurney got Ford back on side with his pitch. Ford was already developing a lightweight, alloy version of the Fairlane’s V-8 engine for Indy. The group devised a plan to use the engine in the new Lotus cars, with red-blooded Gurney behind the wheel.

Gurney and Chapman left Ford’s Dearborn office with an agreement from the firm to supply engines and pay for the 1963 project. They brought in Jim Clark as the other driver.

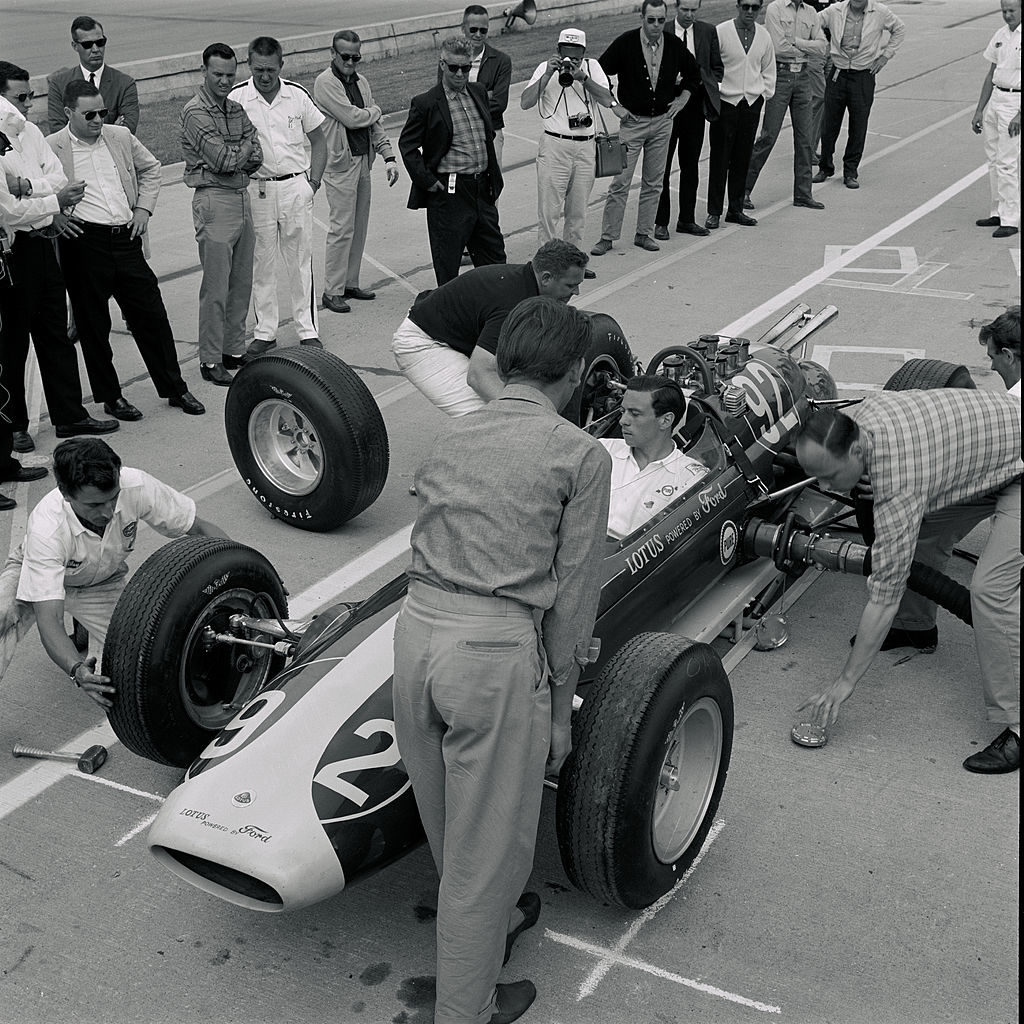

Jim Clark in his Ford-powered Lotus 29 as crew members practice tire changes and re-fueling. (Photo by Bob D’Olivo/The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images)

While Chapman might have had his eyes on the Indy winnings, Gurney was primed to make some dough before the newly formed team ever took to the grid, reportedly earning $180,000 ($1.65M in 2022) on the brokerage.

After some serious development, Ford was able to pull 365 horsepower out of the V-8 on race fuel. The methanol-burning Offy engines were producing north of 400 ponies, but the Ford required two fewer fuelings during the race.

Dan Gurney and Colin Chapman during practice for the 47th running of the Indianapolis 500 on May 25, 1963. (Photo by Bob D’Olivo/The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images)

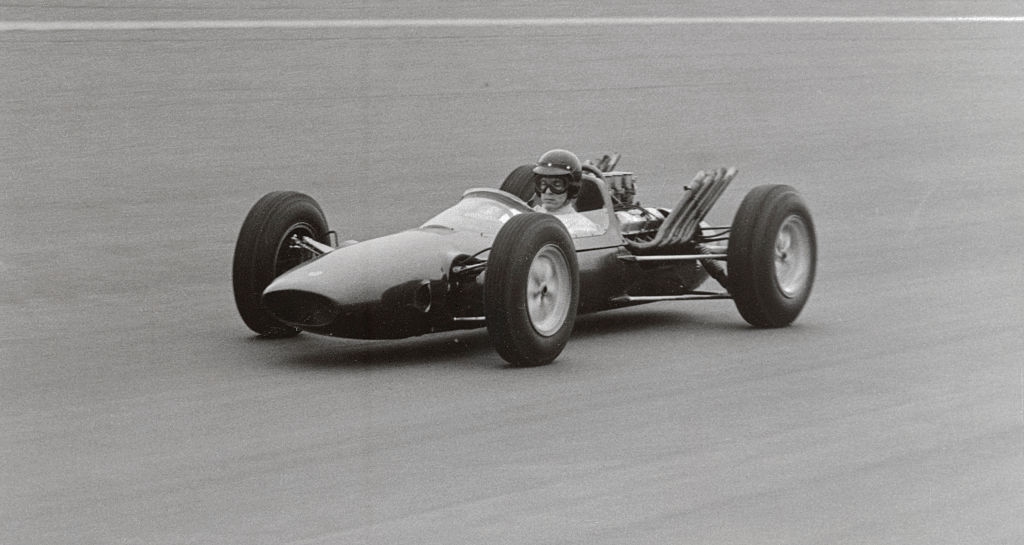

Lotus, meanwhile, set to work refining the Lotus 25 for its two star drivers. Compared to the F1 car, the newly minted Lotus 29 was heavier. It also had asymmetric suspension links for the 2.5-mile track’s four left turns; the 25s were symmetrical. In one of its first practice sessions, with Gurney at the wheel, the Lotus 29 set the second-fastest lap ever turned at Indy.

Dan Gurney behind the wheel of the Lotus 29 prototype.

Dwarfed by the monster, front-engine roadsters, the two Lotus cars backed up their pre-season speed in qualifying for the 1963 Indy 500. Clark lined up seventh, with Gurney 17th.

In the race, Gurney finished seventh and Clark came home second. Many felt the foreign Lotus was robbed of the win after American hero and eventual winner Parnelli Jones escaped punishment leaking oil in the closing stages. Nonetheless, second was still worth $100,000 ($917,000 in 2022).

It was a remarkable debut for Chapman, Lotus, and Ford. “When you were part of his team you quickly came to realize this was a guy working at redefining the cutting edge of racing technology. That was a real motivating factor,” Gurney once told journalist Alan Henry.

Despite the apparent success, Gurney felt uncomfortable being linked to the project. Many within the Indy community resented Ford for pumping dollars into a team with roots outside of America. Results weren’t kind to Gurney either. His Lotus was withdrawn from the 1964 Indy 500 because of trouble with its Dunlop tires. And in 1965, while Clark had his Indy breakthrough in the Lotus, Gurney’s engine broke after 100 miles.

Jim Clark celebrates victory at the 1965 Indy 500. (Photo by Bob D’Olivo/The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images)

Automotive historian Leo Levine recalled: “Gurney, the man who was the catalyst in the program, was also the man who got the short end.”

It wasn’t all bad for the Big Eagle. Gurney used the winnings from his Indy stints to establish his fledgling All American Racers team, which would become one of the perennial powerhouses at the Brickyard.