“Who are those guys?”

Connoisseurs of the western movie genre will recognize this line from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. In the film, intrepid bank robbers played by Paul Newman and Robert Redford crisscross the country and flee to Bolivia in an effort to escape from the law. No matter where they go, a posse finds them. Frustrated and a little bit mystified, Butch and Sundance repeatedly ask one another, “Who are those guys?”

I thought of this line when I heard that Teddy Yip Jr. and his Theodore Racing team would be entering two cars in the 2022 Macau Grand Prix. You may be wondering what a late ’60s movie about two photogenic outlaws has in common with a one-off formula car race in southern China. Allow me to connect the dots.

- Yellow and black barriers lined the technical and tricky Macau street course. (Photo by Cheong Kam Ka/Xinhua via Getty Images)

- Crashed cars are lifted from Macau’s tight confines. (Photo by Robert Ng/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

Teddy Yip Sr. was a fabulously wealthy, famously eccentric Macau businessman who spoke seven languages, plus six dialects of Chinese, and habitually referred to himself in the third person: “Teddy would like a martini.” Through his chronically underfunded Theodore Racing team, he entered cars in Formula 1 and at the Indy 500 in the 1970s and 1980s. But his first and most enduring love was the Macau Grand Prix.

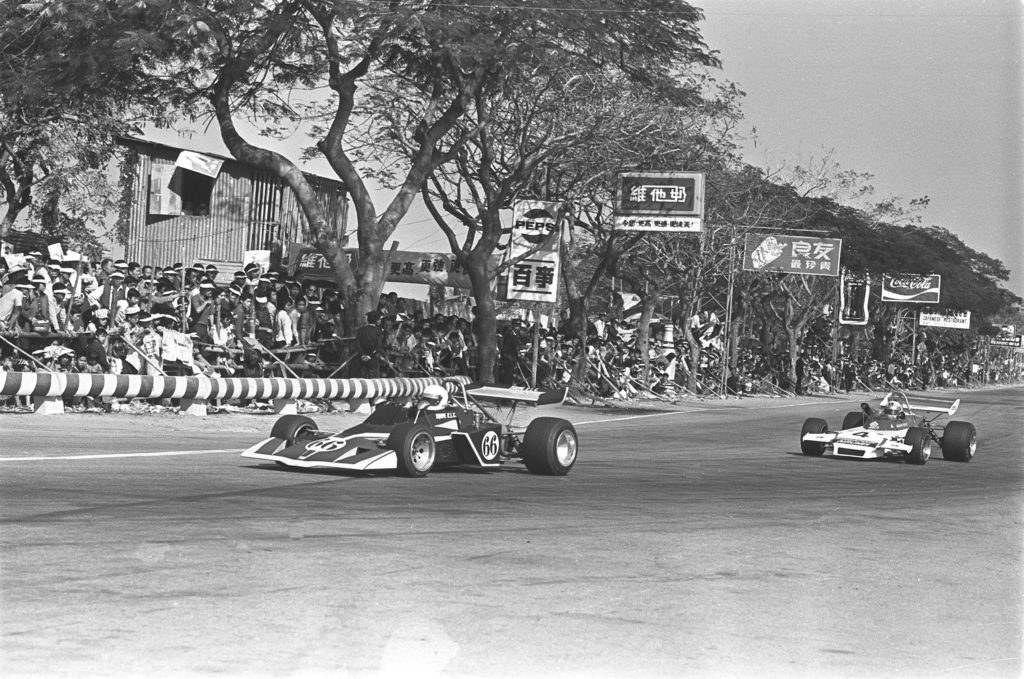

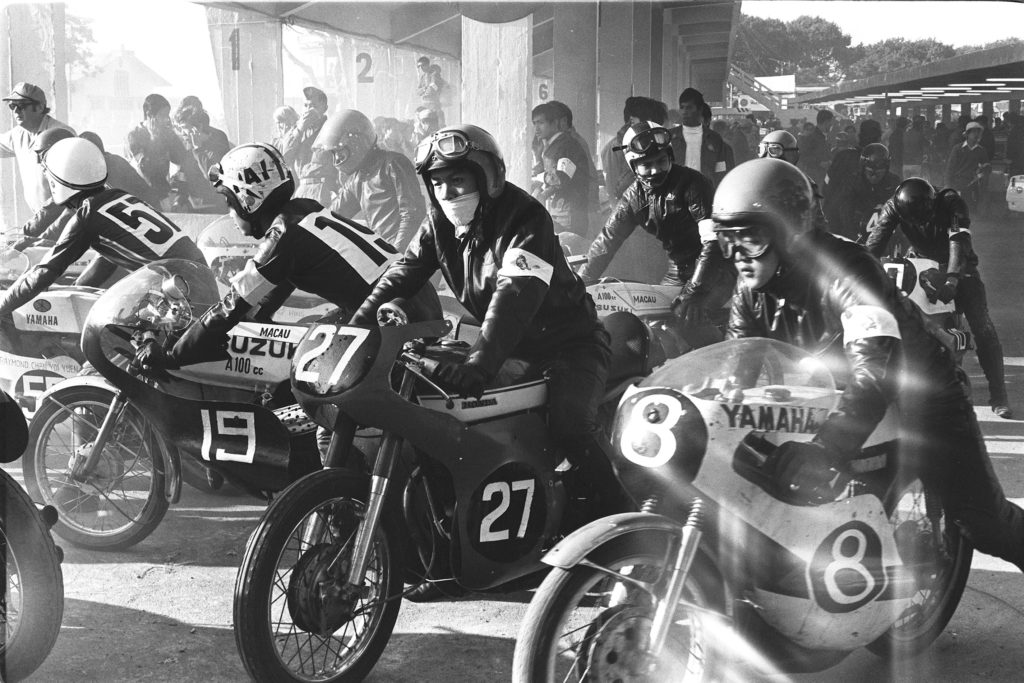

- 1973 Macau Grand Prix (Photo by CHAN KIU/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

- 1971 Macau Grand Prix (Photo by CHAN KIU/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

The most densely populated urban center in the world, the semi-autonomous city of Macau boasts a gambling industry seven times larger than Las Vegas’. In 1954, a group of businessmen put together a street race for sports cars to entice foreigners to visit the area’s many resorts and casinos. Yip raced there three times during the 1960s and promoted the event through his oversized personality and epic parties.

In 1974, the organizers created a separate race for open-wheel cars featuring an Asian take on America’s Formula Atlantic racers, aptly called Formula Pacific. The grand prix wasn’t part of any championship; in fact, it was held after the season had ended. Precisely for this reason, Macau became an event where up-and-coming formula-car drivers competed for the attention of sponsors and team owners. The roster of winners includes countless champions, such as Michael Schumacher.

Martin Brundle of the Marlboro-Theodore team in the 1983 Macau Grand Prix. (Photo by C. Y. YU/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

In 1983, the race graduated from Formula Pacific to Formula 3 cars, an international racer that attracted drivers from all over the world. The 25-car field included seven drivers who would later advance to Formula 1. There were also three Americans—Davy Jones and Price Cobb, both of whom would win the 24 Hours of Le Mans … and Bob Earl.

Earl was an emerging wheelman who won races in Formula Fords, Super Vees, and Atlantics but suffered from a common motorsports affliction: He had more talent than money. In 1981, with no immediate prospects on the horizon, he entered the Macau Grand Prix with the hope that a good result would jump-start his career.

Against all odds, Earl outran a field that included seven drivers who would later race in F1, becoming the first—and thus far only—American to win in Macau.

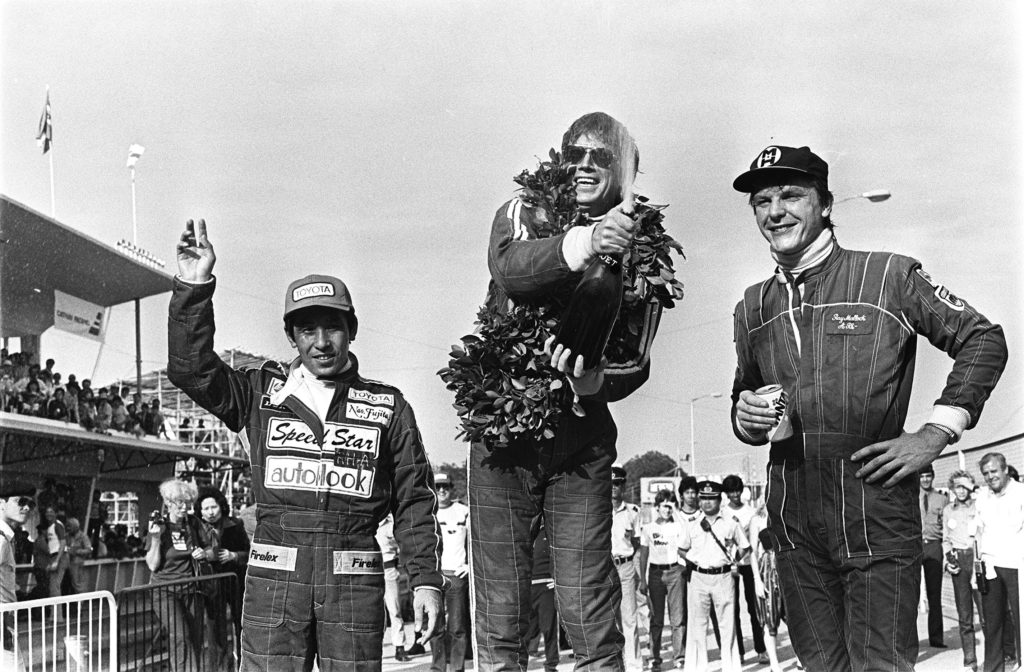

American driver Bob Earl sprays champagne after winning the 1981 Macau Grand Prix (Photo by SUNNY LEE/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

Alas, the victory didn’t bring him fame and fortune. His prize money amounted to $36, and he spent the following night on the floor of journalist Steve Nickless’s hotel room. Adding insult to injury, car owners back in the states were unimpressed by his performance on the other side of the globe.

Early missed the race in 1982 but he returned to Macau in 1983. This time, he was accompanied by Carroll Smith, the former Shelby American team manager who’d more or less invented the job of race engineer. Practice went badly. Earl’s engine was down on power, and the engine builder, who was focused on helping better funded drivers, blew him off. Also, Earl was unfamiliar with the Formula 3 cars that most of his rivals had been racing all year.

“I talked to Mike Thackwell and Stefan Johansson,” Earl says. “They were very nice, but they said you’ve got to toss the car around like a rally car. That didn’t make sense to me, because I’d worked hard being fluid all my life, and that was just going to scrub speed.”

Earl decided that he’d get some real-world pointers by following in the tire tracks of the driver at the top of the time sheet, a young Brazilian named Ayrton da Silva who was driving for Teddy Yip. Earl made sure he was first in line when the next session began. He allowed da Silva to pass him, then stayed right on tail—at least for a while. When Earl returned to the pits, he was frustrated and perplexed, just like the two leads in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

“I’ve got good news and bad news,” Earl told Smith.

“What’s the good news?” Smith asked.

“The good news is that I’m doing it right. That guy is smooth as silk.”

“So what’s the bad news?”

“He pulled me two feet on the exit of every corner,” Earl said. “Who is that guy? I don’t think I can beat him.”

Hamstrung by his dud engine, Earl finished 9th and 10th in the two heats and was classified 8th overall. Da Silva won both heats from the pole to stand on the top step of the podium next to Roberto Guerrero and Gerhard Berger. Four months later, da Silva was in Formula 1, using his mother’s maiden name: Senna.

Ayrton Senna celebrates his victory at the 30th Macau Grand Prix. (Photo by LEE/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

Earl eventually became a stalwart in IMSA, winning countless GTU and GTP Light races and finishing first overall in the 12 Hours of Sebring in a fire-breathing Nissan GTP car in 1990. Later, he was a premier instructor and driver coach. But he never forgot the master class he took with Senna during that practice session in Macau.

“You get to certain points in your career when you realize you might not be the quickest guy in the world,” he says. “But since it was Senna, I didn’t feel so badly about it. He dominated everything he was in. I wouldn’t say that he was driving the snot out of the car, but he was driving it to every limit he could find.”

Earl wasn’t able to match Senna on the track. But when it comes to Macau Grand Prix wins, they’re dead-even—one apiece.

- Drivers compete during the Sands China Formula 4 Macau Grand Prix final race at the 69th Macau Grand Prix on November 20, 2022. (Photo by Eduardo Leal / AFP) (Photo by EDUARDO LEAL/AFP via Getty Images)

- Drivers compete during the Melco Great Bay Area GT Cup race at the 69th Macau Grand Prix on November 19, 2022. (Photo by Eduardo Leal / AFP) (Photo by EDUARDO LEAL/AFP via Getty Images)

- Macanese driver Lam Kam Sa passes while the yellow flag is raised during the Sands China Formula 4 race at the 69th Macau Grand Prix on November 19, 2022. (Photo by Eduardo Leal / AFP) (Photo by EDUARDO LEAL/AFP via Getty Images)

- The congested Macau street course is a training ground for emerging drivers aboard Formula 3 racers. (Photo by David Wong/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

- MACAU, Nov. 22, 2020 — Smartlife Racing team driver Leong Hon Chio of China’s Macau races during the final race of the Formula 4 Macau Grand Prix in Macau, south China, Nov. 22, 2020. (Photo by Cheong Kam Ka/Xinhua via Getty) (Xinhua/Cheong Kam Ka via Getty Images)

- The 33rd Macau Motorcycle Grand Prix gets under way 20 November 1999 in Macau, for the last time before China assumes control of the Portuguese-administered enclave. The enclave of Macau reverts to Chinese rule at midnight on December 19, 1999 after 442 years of Portuguese administration. AFP PHOTO (Photo by – / SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST / AFP) (Photo credit should read -/AFP via Getty Images)

- 1979 Macau Grand Prix (Photo by POST STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

- Hans Stuck of Marlboro BMW team in action during the Guia race of the 31st Macau Grand Prix. November 1984 (Photo by POST STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER/South China Morning Post via Getty Images)

Earl’s comment about Senna is familiar. I bought a car from a Mexican driver who had made it to the world finals in karts. Among the best kart drivers in the world, at Monza, Senna just out shone them all in practice. So, all the drivers were standing around staring at Senna’s kart. No cheater. Nothing to hide on the kart. They all acknowledged that Senna was just driving on another plane from ALL of them. Too bad be was no great sportsman.

Great info and history in this article! Sometimes the stories (especially with Senna) become much larger than the truth. Yes, he both won and was fast in 83. But so was Berger, who had fastest lap of that race finishing 3rd.

Patrese even managed consecutive wins there years earlier. The tales are just much larger with Senna, and with On-board coverage and rabid fan base many other drivers accomplishments are drowned out. Just a guess, but prime Fangio probably would have put on a clinic at Macau to all comers of any era.

We need more articles like this one.