Rules are to race car builders as passwords are to hackers: pesky annoyances that are meant to be circumvented. Is that cheating? Only if you get busted. As Darrell Waltrip put it after he and A.J. Foyt had their qualifying times for the 1976 Daytona 500 tossed out because they were packing hidden nitrous-oxide bottles: “If you cheat and don’t get caught, you look like a hero. If you cheat and get caught, you look like a dope. Put me where I belong.”

Since the dawn of motorsports, tech inspectors charged with enforcing the rules have been engaged in a never-ending game of whack-a-mole with car builders determined to evade them. To be fair, a lot of straight shooters operate in the gray area between right and wrong—such as Roger Penske, who dominated the Indy 500 in 1994 with pushrod engines that exploited a loophole in the USAC rulebook. But it’s no coincidence that the winner of the first-ever NASCAR race in 1949 was disqualified for using illegal springs optimized for running moonshine.

Progress being what it is, the bad guys have gotten a lot more sophisticated since then. Here’s a top 20 list of the most ingenious cheats of the past half-century:

Bumper Drafting

(Photo by Eric Schweikardt/Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

Bobby Allison cruised to a 22-second victory in the Daytona 500 in 1982 despite losing the rear bumper of his Buick Regal on Lap 3. Or maybe he won precisely because his notoriously creative (euphemism alert!) crew chief, Gary Nelson, made sure the bumper would fall off. Although Allison denied that the missing bodywork improved aerodynamic performance, he magically ran the last 100 miles on a single tank of gas without the benefit of a drafting partner. Nelson was later named NASCAR’s chief tech inspector. Talk about putting the fox in charge of the henhouse.

Hot Seat

Mario Andretti driving the STP Hawk III/Ford TC on his way to winning the 1969 Indianapolis 500. (Photo by ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images)

After wrecking his Lotus 64 during practice for the Indy 500 in 1969, Mario Andretti was forced to drive his backup car, a Brawner Hawk that habitually ran hot. Although he qualified second, his oil temperature was off the charts, and USAC refused to allow the car to be fitted with an external oil cooler. Cue the Mission: Impossible crew. During an all-nighter, an oil cooler was concealed behind Andretti’s seat. The next afternoon, Andretti’s back was badly blistered—but he didn’t feel a thing until long after winning the race.

Ghost in the Machine

Michael Schumacher celebrates winning the French Grand Prix. (Photo by Claire Mackintosh/EMPICS via Getty Images)

Ayrton Senna was the first rival to complain that Michael Schumacher was illegally using traction control in his Benetton B194. After the French Grand Prix in 1994, where Schumacher sliced into a commanding lead from third on the grid, the FIA examined the software in his car’s ECU. Lo and behold, engineers found a subroutine helpfully labeled “launch control.” But since they couldn’t prove that this apparent smoking gun had been fired during a race, the jury declined to convict, and Schumacher went on to win his first world championship.

Head Fake

When Volvo entered the British Touring Car Championship in 1994 with the 850 estate, nobody could understand how the boxy station wagon kept pulling away from the competition on long straights. The car’s secret? The inline five-cylinder engine didn’t have its head on straight—literally. Tom Walkinshaw Racing had cleverly machined a wedge out of the stock head so it sat at an angle on the block, making the inlet port steeper than stock while the exhaust port was shallower. Better breathing helped TWR “find” 65 horsepower.

Virtual Ringer

Daniel Abt competing in Formula-E. (Photo by Xavier Bonilla/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Pity poor Daniel Abt. Although he was a race winner in the all-electric Formula E series, he was a noob when it came to esports, the playing of virtual sports online. And he was completely out to lunch after Formula E shifted to a virtual, online format in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, you can imagine how eyebrows shot up when he unexpectedly qualified second and finished third in the mid-season “Stay at Home” race at “Berlin.” Turns out that he’d sneaked in a ringer, secretly handing the controls to pro gamer Lorenz Hoerzing to race for him. Although Abt insisted this switcheroo was a harmless lark, the FIA was not amused. He was disqualified, fined 10,000 euros, and fired by Audi.

Restrictor Plate Special

Ever since restrictor plates were instituted to starve engines of air (and, therefore, power), engine builders have been angling to bypass them. Ford engineers developed a slick end run in their 2003 Focus RS World Rally Championship contender. When excess air passed through the restrictor plate during off- and part-throttle operation, it was routed through a long tube to a titanium tank concealed inside the rear bumper. When the driver buried the throttle, a butterfly valve opened and stored air flowed back to the engine, boosting power by 5 percent. The system was technically legal, since the spare air had already gone through the restrictor plate. But the FIA decided it was too clever by half, and it was banned after three races.

Brake Check

Necessity is the mother of invention. In 1982, Formula 1 teams using normally aspirated Cosworth engines were outgunned by the turbocharged Ferraris and Renaults. At the time, teams were allowed to top up cooling fluids after a race and before weighing by the scrutineers. So Gordon Murray at Brabham and Patrick Head at Williams fitted their cars with large water tanks, ostensibly to cool the brakes—nudge, nudge, wink, wink. The water evaporated almost immediately, allowing the cars to compete underweight before being ballasted after the checkered flag. A Brabham BT49D and Williams FW07C finished first and second in the Brazilian Grand Prix—and both were promptly disqualified.

Repeat Offender

Jimmie Johnson celebrates after winning the NASCAR Nextel Cup Daytona 500, in 2006.(Photo by Jonathan Ferrey/Getty Images)

Crew chief Chad Knaus embodies the NASCAR dictum “If you ain’t cheatin’, you ain’t tryin’.” Even as he won seven championships with driver Jimmie Johnson, Knaus was dinged for rules infractions on more than a dozen occasions. His craftiest workaround was rigging the track bar adjuster so that rotating the jackscrew caused the rear window of Johnson’s No. 48 Chevy Monte Carlo to rise outward, diverting air from the rear spoiler and maximizing top speed during qualifying for the 2006 Daytona 500. Knaus was suspended for four races and fined $25,000. While Knaus watched on TV, Johnson won the race anyway.

Flexi-Flier

Movable aerodynamic aids are a no-no in F1. But in 2010, as Sebastian Vettel was driving to the first of four consecutive world championships, two eagle-eyed journalists noticed that the front wings of his Red Bull RB6 were closer to the pavement on track than they were in the pits. How to explain this mystery? Designer Adrian Newey had come up with a method of laying up carbon fiber so the wing could droop under aerodynamic load while still passing the FIA’s rigidity test. After Red Bull’s outraged (and out-foxed) rivals complained, a more stringent test was instituted in 2013.

Bottom Line

What’s the best way to hide an aerodynamic aid? Stick it where the sun don’t shine. Exhibit A was the floor of the Ferrari F2007 F1 car. By attaching it to the chassis with a hinge at the rear and two adjustable springs at the front, the flexible floor allowed the car to be set up lower than the competition, making it more efficient aerodynamically. Also, it could be run more aggressively over curbs, allowing drivers to straight-line chicanes. In Australia, the first race of 2007, Kimi Räikkönen qualified on pole and won effortlessly. The aero police at the FIA then devised a new rigidity test that consigned Ferrari’s movable floor to history’s dustbin.

Waste Not, Want Not

OK, this one really gets into the weeds, but that’s where the best cheats usually lurk. At the Indy 500 in 1979, USAC specified that the inside diameter of the wastegate, or the device that regulates the pressure of exhaust gases routed to the turbo’s turbine, had to be 1.470 inches wide. But by using a wider tube and then inserting an obstruction, such as a washer, some teams met the letter of the 1.470-inch law while creating back pressure that allowed them to defeat the pop-off valve and benefit from increased boost pressure. By using this subterfuge, Dick Ferguson, Tom Bigelow, and Steve Krisiloff bumped their way into the field before being found out and disqualified. After a DQ’d team filed suit seeking an injunction, USAC agreed to an unprecedented fifth day of qualifying, and Krisiloff and Bigelow, stripped of their cheat, made the show after all as the 34th and 35th starters.

Pedal Power

A view inside of the cockpit footwell from the #8 West McLaren Mercedes McLaren MP4/12 Mercedes V10 of David Coulthard showing the small second brake pedal on the left. (Photo by Darren Heath/Getty Images)

In 1997, photographer Darren Heath couldn’t understand why a rear brake rotor on the McLaren MP4/12 F1 car was glowing red even as the car accelerated out of corners. He found a clue inside the cockpit, where he spotted a second brake pedal. What gives? Designer Steve Nichols had realized that giving drivers the ability to independently apply one rear brake enabled them to dial out understeer, helping the car turn more sharply and allowing the team to run less front wing. It took awhile to perfect the brake-steer apparatus. But after the new-for-1998 MP4/13 kicked holy butt in the season opener at Australia using effectively a form of four-wheel steering, the system was prohibited, the usual penalty for building a better mousetrap.

Double Agent

(Photo by The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images)

Nobody pushes the envelope better than Roger Penske. In 1968, he entered two seemingly identical cars in the 12 Hours of Sebring: a Camaro that had been built for the upcoming Trans-Am season and a stablemate that had been banned the previous year because the body had been dipped in acid to save weight. After running the legal car through Tech, team manager/lead driver Mark Donohue hustled back to the garage, swapped numbers, and got the lightweight cheater approved as well. Then, the team pulled the same trick in reverse so Donohue and Bob Johnson could both qualify in the acid-dipped model. Penske’s Camaros finished 1-2 in class, but Donohue wasn’t sure who was driving which car. “It was even confusing for us to keep track by then,” he wrote in his aptly titled memoir, The Unfair Advantage.

Heavy Water

By 1984, the FIA no longer allowed water to be added to cars after a Formula 1 race to make weight. So Tyrrell, the only non-turbo Cosworth team left standing, dreamed up a hack. During a late-race pit stop, mechanics filled the tank for the engine’s water-injection system with water supplemented with 140 pounds of lead shot. After Martin Brundle finished a magnificent second in the Detroit Grand Prix, a postrace inspection found traces of hydrocarbons in the water. Tyrrell argued that the unusual form of lead ballast was legal (the rules were indeed ambiguous) but the FIA investigators accused the team of using prohibited fuel additives, and they went ballistic. Tyrrell was banished from the last three races of the year and stripped of its championship points for the season.

No Joke

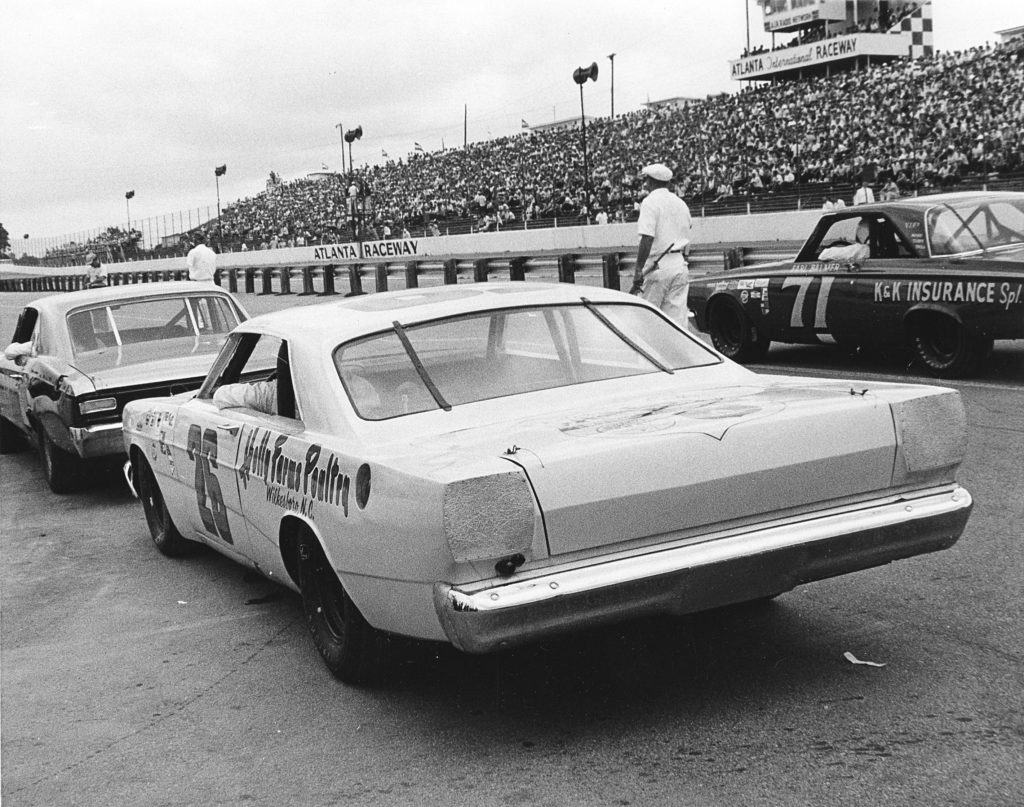

NASCAR legend Junior Johnson raised chickens, hogs, and cattle on his farm. In his race shop, he cultivated a banana. Technically, it was a Ford Galaxie that NASCAR founder Bill France had asked him to build in 1966 to goose flagging attendance. Johnson showed up at the Dixie 400 in Atlanta with the wildest stock car anybody had ever seen.

(Photo by ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images)

The nose of the car was steeply raked to reduce drag while the rear end had been raised to generate downforce. Meanwhile, the top had been chopped so radically that driver Fred Lorenzen could barely squeeze through the window. The shape and distinctive Holly Farms Poultry livery inspired onlookers to dub it “The Yellow Banana” or, less charitably, “Junior’s Joke.” Lorenzen was leading when he hit the wall, and Johnson was told to take his Galaxie home—permanently.

Blown Cover

In drag racing, nothing offers more instantaneous bang for the buck than injecting nitrous oxide into an engine. Nitrous is also a cheater’s friend because the delivery systems are simple to plumb and easy to hide. (Drivers have been known to avoid detection by carrying canisters in their firesuits.) Rumors of widespread nitrous use were rampant during the heyday of Pro Stock, but only one team was outed. Technically, you might say the team outed itself. In 1997, shortly before the qualifying session for an NHRA event in Columbus, Ohio, the paddock was rocked by an explosion. A small metallic bottle was found on the pavement, spewing a gas later identified as nitrous oxide. An investigation determined that crew chief Bill Orndorff had cached the canister inside the oil cooler. After driver Jerry Eckman fired up the engine, the oil temperature rose, and the nitrous bottle exploded. Oops!

What Goes Up Must Come Down

For the 1981 Formula 1 season, the FIA set the minimum ride height at 6 centimeters. Gordon Murray reasoned that this figure applied only to scrutineering. So he designed the Brabham BT49C with soft springs and cylinders filled with water and hydraulic fluid at each corner. At speed, downforce pushed fluid from the cylinders through pinhole orifices to a central reservoir, allowing the car to run closer to the ground, thereby increasing aerodynamic efficiency. But on the cooldown lap after the race, fluid seeped back into the cylinder, and the Brabham rose to meet ride-height regulations. To divert attention from his hydropneumatic system, Murray fashioned a dummy aluminum box with nonoperational electric wires. But after Nelson Piquet’s magisterial win in Argentina, other designers cottoned on to Murray’s trick and conjured up ride-height kludges of their own.

One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Gene Felton at the wheel of an Oldsmobile Calais during an IMSA Kelly American Challenge race, in 1985. (Photo by ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images)

The rules for the Kelly American Challenge, which ran from 1977 to 1989, based minimum weight on engine size. To determine engine size, a tech inspector measured the displacement of one cylinder and then multiplied it by the number of cylinders. Sounds cut and dried. What could go wrong? Well, in the engine bay of Tommy Riggins’ Chevy Malibu, one cylinder was especially easy to access, so it was used to measure engine size. But at Road Atlanta in 1983, a contrarian tech inspector chose to check a different cylinder and came up with a different displacement number. How? The cylinder that was usually tested was undersized, while the one on the other side of the V was correspondingly oversized. So even though the engine was legal, the car was too light since the minimum-weight calculation was based on the Mini-Me cylinder.

Plategate

Toyota Team Europe came up with an insanely sneaky way to bypass the restrictor plate during the 1995 World Rally Championship season. The hose that connected the air intake to the turbocharger of the Celica GT-Four was fitted with a metal collar. Screwing it into place compressed elastic washers, thereby moving the restrictor plate 5 millimeters away from the turbo. This allowed air to pass around the plate rather than through it. Hello, 50 extra horsepower! But the real genius of the design was that the very act of taking the unit apart to inspect it released the tension on the springs and caused the restrictor plate to snap back into its original, legal position. The fiddle wasn’t discovered until Rally Catalunya, near the end of the season. The FIA stripped Toyota of all points in 1995 and excluded the team from the 1996 championship.

Smokey’s Bandit

You know those wild stories told about the Chevelle that Smokey Yunick didn’t race in the Daytona 500 in 1968? That it was seven-eighths scale? That Yunick drove it back to the Best Damn Garage in Town after leaving the gas tank with mystified tech inspectors? Bogus, most of them, but it’s still the greatest cheater car in racing history. There was virtually no piece of that Chevelle that Yunick didn’t massage. The chassis was scratch-built, with a Watt’s linkage and faired-in suspension components. The engine was positioned on the centerline of the chassis, as required, but Yunick moved everything else to the left, including the driver. To optimize aerodynamics, he shaved the door handles, channeled the grille, and flattened the roof. Yunick insisted the car didn’t break any rules. But as he wrote in his memoir: “Was this car a ‘cheater,’ Smokey? You’re goddam rite [sic] it was.”

(Photo by ISC Images & Archives via Getty Images)

Back in the mid 60’s, Smokey took a Corvair or VW van and worked his majic on it, He made little fairings for all the exposed bolts out of bondo, and took off the mirrors, and smoothed the front end, and it went something like 15 MPH faster. He didn’t touch the engine, but smoothed every thing he could see.

I had no idea Smokey did all that to a Corvair. Very cool!

What about thr time Smokey flat towed a Camaro out to Riverside Raceway, went out in practice ans was seconds faster thst anyone else, put the street ties back on it and left the track!!!

Absolute legend.

Really? A car motorsports article with a picture that is obviously not what is noted in the text? If the writers or editors don’t know the difference between Darrell Waltrip’s #88 Gatorade Oldsmobile and Bobby Allison’s #12 Miller Buick they need to move down to the pressroom and let somebody more knowledgeable about NASCAR do those articles.

Great catch, Jim! Just added a new photo of Allison in the 1982 Daytona-winning Buick.

That is Bobbie Allison’s Gatorade Buick in the photo, not an Oldsmobile. NASCAR switched to the “downsized” GM cars in 1981. By then, Darrell Waltrip no longer drove the Gatorade sponsored car and was driving for Junior Johnson in the Mountain Dew Buick, which is visible in the background of this photo.

The photo is correct for 1982, even though the text doesn’t say what the photo is other than ‘(Photo by Eric Schweikardt/Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)’

This is a great review of some of the best innovation’s from great innovators in Auto racing!

Thank you, Thomas!

What about Darrel Walthrip and his chassis full of bbs that were jettisoned during the race. Too bad he was caught when a bunch fell out of pit road hitting a bunch of competitors mechanics…..

Such a great story. Just heard that one on Dale Jr Download.

I have been a long time student of the unfair advantage.

One of my greatest meetings have been with Smokey Yunick and Junior Johnson.

This list is nice but as a student of these activities NASCAR by far was the best at the grey area and pulling off these amazing tricks.

Dale Jr said it best as any crew chief not pushing the boundary is not doing his job.

We often hear the Darrel buck shot story and others but there are 20 more untold stories that tell much more.

The Old Milwaukee GP that was 3 inches longer than legal. They modified the template while acting like they traced them. Bobby Allison that had breakaway bumper bolts and was faster with no rear bumper.

Terry Labonte starting a race with lead in his wheels only to create his own caution to change tires and win the race. Cale with water in his tires.

Dale SR with a narrow rear bumper caught in inspection at Daytona. The crew changed it out and put the same size bumper on and NASCAR never rechecking it for the race.

NOS2 in the frame of the car but the switch and regulator in the Driving suit of Waltrip.

Bill Elliot’s Talladega win T Bird that was under sized. It’s still in the Henry Ford Museum. It fit the templates but was 7/8th the actual size in other spots.

Soon in the springs to get on track then the wood would snap and fall out to lower the car.

Intakes with sliding panels to avoid the Restrictor plate..

Traction control bondo’d into the floor pan to hide the wires. Special chips in the MSD box to control traction then the driver tossed the chip to hide it. Then NASCAR putting up mics at Martinsville to catch the cars using the electronics to control tire spin.

You could go on and on.

This is the cool stuff about racing.

Even at the local race track we and others pressed the rules often. Even in soap box derby racing I saw things being don often. Axles bent to run on one of two bearings on wheels with one bad bearing. Yes they went beyond the electro magnet of the 70’s and I have been a victim of these tricks at times.

I would recommend the 3 book series on Smokey and the Unfair Advantage by Mark Donahue.

Also Chevy Racing? About the cover racing Chevy did in the 70’s when GM banned racing.

I agree. NASCAR crews were the best in rulebook margins. Great additions, hyperv6!

I can’t believe they didn’t mention Yunick’s fuel line under the seat. Like two more gallons, that one is classic.

Gotta admire the ingenuity of people but a win isn’t a win if the rules aren’t followed. Hollow victories aren’t worth celebrating.

But the race is fun to watch and talk about later….even years later

Tell that to the record books The winner could care less , & Ive been racing for 35 years & thats the truth

Mark Donahue used a toggle switch to turn his Penske Trans Am Series Camaro’s brake lights on to fool somebody behind him into braking early.

I did that too!

You don’t even need to be cheating to be accused of it and thrown out of races. SCCA rules for a class stated that “gaskets are unrestricted”. The Datsun factory team machined an engine for me that o-ringed the block to eliminate the cylinder head gasket. A gasket was added under the cam towers to optimize the geometry. Oil passed through these “head saver shims”, so it should have been legal.

“Balancing and blueprinting are permitted” was another rule, and Datsun specified only lift measurements, so the shop had their camshaft grinder build a blueprinted stock cam. Cam timing was adjustable on factory parts, but offset bushings were machined for blueprinting purposes.

A two page list of protested items was filed against me after winning several races, and the Competition Board ruled against me on the camshaft towers and offset bushings. An attorney on the board wrote me a letter, apologizing for the decision. He was obviously in the minority.

Over the winter lull we figured out how to meet the rules as requested. We welded up the aluminum cam towers and remachined them to the blueprinted height we wanted, and used an oversized pin in the camshaft that was ground down to the factory diameter on the gear side. This mated to the factory cam gear. It was also set to the blueprinted advance amount. Now with things done to the SCCA preference, we started with improvements. We changed out the clutch. Clutches were unrestricted, so the flywheel was modified to fit a 7.25″ twin disc clutch. The whole assembly weighed A LOT less than the stock 11″ system. We got away from the locked diff that everyone was using, and bought a brand new Torsen differential from that factory race shop. We used 2.5″ springs, instead of the 4″ springs, giving us more clearance for wider wheels under the stock bodywork. We went with a lighter sway bar, since we could tune the car with the proper spring weights. We built a one-piece front spoiler that extended back under the engine to improve air flow. One model of the gearbox from the factory had taller second and shorter third gears, and that box was found in a junkyard and rebuilt with modified synchronizers for faster shifting. All told, the car horsepower didn’t change from the 250 hp “illegal” version, but the lighter flywheel and improved driveline made a one second difference on a two mile, ten turn track. We won the championship after surviving a season of monthly teardowns from the protests.

I remember a comment from a corner worker that my car sounded like a GT2 car. I didn’t say a thing, but the factory shop that built the engine and driveline told me the only difference between my engine and their National Champion GT2 car was the milder blueprinted camshaft and stock twin carbs on my car. The cam lowered the redline to 8000 RPM’s, versus the nine grand limit with better breathing from triple Mikunis and race cam. Most people shifted at the stock 7000 RPM limit. The extra thousand RPM’s and lower gearing could be heard by discerning listeners (and measured by the stopwatch).

Such a great story, VA danno! Innovation at its finest.

Was it Smokey who used an oversized fuel line to get past the NASCAR 22 gallon fuel limit rule?

It was!

NASCAR has a little known rule concerning finishing the race using the same engine you started with. There ARE reasons for every silly thing in NASCAR, aren’t there?

When Classic motorsport was restoring a Group 44 Triumph they couldnt get the busings out of the control arms, ended up that they were rose jointed and the original bearings were sectioned so they looked like stock from the outside

Alderman’s Dodges in Pro Stock with Nitrous , along with AJ Foyts stock car with it running through the starter cable from inside the roll cage There are so many legendary cheats its crazy.

One of my local favorites on an ITS race @ Road Atlanta Tech was checking ECU’s for aftermarket chips, one crew chief came up & thought the car was teched & started the 944 & drove away with the tech inspector holding his ecu! He had wired a dummy to pass tech. Also another great idea was windshield washer fluid being refilled during an Escort race , come to find out they were using it to cool the brakes . Inginuity at its finest .

I loved how Gary Nelson was one of the great cheaters to the point NASCAR made him the series tech inspector.

Penske was big on acid dipped bodies. Also the Cooled high refueling rig.

Smokey once had the Chevelle with the fenders not cut out. They complained it was illegal but there was no rule in cutting. So his critics said let him go as he can’t change tires in the Daytona 500.

After qualifying he cut the fenders. His critics said he can’t do that but there was no rule on cutting again.

Lead radios and helmets. Hidden gas tanks etc.

Many teams brag today but Petty Enterprises still get a bit buggy if you ask about any grey areas. Dale Inman is very defensive. But Maurice Petty’s sons easily admit the big engine in Charlotte Because everyone knows about that.

Tires on the Erin side of the cars.

Earnhardt was testing with Mark Martin at Atlanta. They were running for the championship. Childress put the tires on the reverse side and Dale went out and broke the track record.

Roush got suckered into moving to use a Yates car and never could adjust it for the race.

Jon Dodson also has many tales. They had a spoiler with slots. They got caught and had to add more screws. They did with the spoiler laid down as NASCAR never checked it again.

We ran in our car the stock control arm required. Under them we had adjustable rods to move the rear end to turn the car. The bushings were fake and the arms just snapped on.

Always liked the Nelson story. Brought the wolf in the hen house!

When racing stock cars at our local fairground many, many years ago (1970s) our “class” had a rule that anyone could buy you engine for $50 after race night. Kept us from putting too much money into the engine.

Claim rules are the best! Wish more series had them.

Was it Smokey that removed the starter ring gear and then drilled holes radially down onto the flywheel to lighten it. Then reinstalled the ring gear which then hides the holes.